I was recently in a Twitter discussion with Twitter users @colinburgess and @bibhistctxt who had commented on this post I made:

Thus began a back and forth which culminated in yours truly acknowledging that it would be better to write a blog post on this section than to try to tackle it 280 characters at a time. So, here we are! Buckle up and try to enjoy the ride! (Please use only one animal at-a-time.)

Note: Unless otherwise indicated, all scripture citations are from the New Revised Standard Version (National Council of Churches, 1989). All citations of the Greek New Testament are from the The Greek New Testament, fifth revised edition (Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2014).

INTRODUCTION

The episode wherein we find Matthew 21:6-7 is part of the larger context of an event commonly referred to as the “Triumphal Entry.” It is a story told in all four Gospels: Matthew 21:1-11; Mark 11:1-11; Luke 19:29-40; John 12:12-19. Many Christians still commemorate the event on the Sunday before Easter, referring to it as “Palm Sunday” because of the palm branches that the people of Jerusalem placed on the ground before Jesus as he rode into the city. I can recall my days as an evangelical, sitting in my pew, and watching the children of the church walk into the sanctuary brandishing palm branches and laying them down in between the columns of pews. Often we would sing songs that featured the words contained words like “Hosanna” or celebrated the kingship of Jesus generally.

As a theme, the kingship of Jesus is strewed all over the episode, though it is more acute in Matthew for reasons we will discuss in greater detail further on. But a reader of the Gospels would not fail to see the irony of it all. Jesus is greeted by the throngs with shouts of “Hosanna!” only to be executed days later by the throngs of Jerusalem with shouts of “Crucify him!” Even on his cross the words “King of the Jews” were displayed in an attempt to mock him. Great fanfare turned into great maliciousness.

It is not my interest in this piece to discuss the historicity of the Triumphal Entry itself. Whether it happened or not is of no particular interest to me as an exegete of the text. Instead, my focus will be on how the story is told and will include things like word choice and syntax. To do this we will need to begin not with Matthew’s Gospel but with Mark’s. The reason for this has to do with my view of the solution to the Synoptic Problem. I contend that the first Gospel to be written was Mark’s and that both Matthew and Luke use Mark as a source for their own Gospels. I cannot defend Markan priority at this juncture but there are many good resources that help to explain the Synoptic Problem and defend Markan priority. [1]

Following a commentary on the Markan narrative we will examine the Mathean narrative, noting specifically where it differs with Mark. This will, at times, be more technical than most of my readers are accustomed to but I think it is necessary to show what is going on in the text. We will then zoom in on the specific places in the Mathean story of the Triumphal Entry that reveal my main thesis that Matthew includes two animals instead of one because of his desire to portray Jesus as literally fulfilling Zecharian prophecy. We will close this post out with a very brief look at the Lukan and Johannine narratives.

My recommendation to the reader is two-fold: first, be sure to read the relevant biblical texts so that you may be familiar with them, and second, read only a section at a time and then reflect before moving onto the next section. Please be aware that I have in no way attempted to offer an exhaustive look at the passages discussed and there will be places where clearly more could (and perhaps should) have been said. Sometimes the endnotes will expand on ideas that need not be included in the main text or point to resources that the reader should consult. I’m a firm believer in reading endnotes/footnotes and I hope you are as well.

THE TRIUMPHAL ENTRY IN THE GOSPEL OF MARK

The Gospel of Mark has been called “a passion narrative with an extended introduction.” [2] The reason for this is clear even from a cursory reading: the end of Jesus’ life takes up a significant portion of the Gospel. Following the introduction (Mark 1:1-15 or 1:1-13), the first major section of Mark’s Gospel covers his public ministry (1:16 [1:14] – 8:26). But beginning in 8:27 (thru to 16:8) the story begins to move decidedly toward the direction of the cross.

From this point on, Jesus’ ministry focuses more narrowly on the disciples, and the ominous threat of his impending death becomes much more explicit. The conflict motif mounts and the events leading to his arrest, trial, and execution shape the narrative. [3]

Throughout the Gospel of Mark, Jerusalem is seen as the source of threats and conflict: the scribes that accuse Jesus of being possessed by Beelzebul come from Jerusalem (3:22), the Pharisees and scribes who criticize Jesus’ disciples of eating with unwashed hands come from Jerusalem (7:1), and while Jesus is in Jerusalem before his death he has repeated negative encounters with the Jewish religious authorities (chs. 11-15). [4]

The story of the Triumphal Entry in Mark is Jesus’ first and only trip to the city of Jerusalem for it is in Jerusalem that Jesus meets his end. His popularity has been building since the incident at the synagogue in Capernaum where he healed a man with an unclean spirit: “At once his fame began to spread throughout the surrounding region of Galilee” (1:22). From that point on, the people gravitate to him, looking for him to perform miracles and to hear his authoritative preaching. Mark employs the term ὁ ὄχλος (“the crowd”) often to refer to the people who follow him. [5] But in reading Mark it is clear that while ὁ ὄχλος is generally receptive of Jesus, beginning in 15:8 the crowd, with the prodding of the Jewish religious authorities, turns on him. As noted earlier, the irony is not lost on readers of Mark that the people welcome Jesus with messianic hopefulness in 11:9-10 but less than a week later they reject him with cries of “Crucify him!” (15:11-15) But this is part of Mark’s theme commonly referred to as the “Messianic Secret.” The crowds perceived him as a miracle worker and missed who he really was. [6] The reader, on the other hand, knows precisely who Jesus is and what he has set out to do.

Mark the Story-Teller

The author of Mark’s Gospel was an accomplished story-teller. While he undoubtedly received much of his material from oral tradition [7], he has managed to weave a story together that is at once cogent and discreet. Many pericopes within the Markan narrative were part of individual stories that the author has edited and put together. But to connect these stories together, Mark has added his own redactive comments and this can be seen in multiple places. His main accomplishment, however, is that he manages to offer some vividness to his story in ways often unparalleled by other Gospel writers.

The enjoyability of Mark’s storytelling is enhanced by the more extensive use of descriptive detail than in the other gospels. Typically, the Marcan version of a miracle story may be twice as long as the equivalent pericope in Matthew, simply because Mark is more vividly descriptive, while Matthew goes straight to the heart of the story….The three miracle stories of the 43 verses of Mark 5 are covered by Matthew in a mere 16 verses. Mark, it is clear, enjoys a good story and relishes the telling of it almost to the point of self-indulgence. [8]

This is true even of Mark’s version of the Triumphal Entry which, as we will see, in Matthew has been abbreviated in some ways to make room for other elements that serve Matthean themes.

In total, Mark devotes 185 words to tell the story of the Triumphal Entry in 11:1-11. As is characteristic of Mark, we see the conjunction καί (“and”) nineteen times. [9] We also see that Mark repeatedly employs what is known as the historic or dramatic present, a phenomenon in which an author uses a present tense verb to describe an event that took place in the past. [10] The use of the historic present by an author is usually for the sake of vividness, to make the story come alive. It is a sign of the story-teller at work.

Although the Gospel of Mark, as we now know it, is the earliest of the written Gospels, it is by no means a primitive or simplistic telling of the story of Jesus. Far from it. In recent studies, then, the role of the author as narrator and oral story-teller has come increasingly to the fore. At the same time, the role of the audience as participants in shaping and reacting to the narrative dramatically has been more widely recognized. Aove all, it must be remembered that the Gospel was meant to be performed, to be heard as interaction between author/narrator and audience in a communal setting. [11]

We see in Mark, then, the work of someone who is telling a story in a way that makes Jesus come alive. With that being said, here is the story of the Triumphal Entry.

When they were approaching Jerusalem, at Bethphage and Bethany, near the Mount of Olives, he sent two of his disciples and said to them, “Go into the village ahead of you, and immediately as you enter it, you will find tied there a colt that has never been ridden; untie it and bring it. If anyone says to you, ‘Why are you doing this?’ just say this, ‘The Lord needs it and will send it back here immediately.’” They went away and found a colt tied near a door, outside in the street. As they were untying it, some of the bystanders said to them, “What are you doing, untying the colt?” They told them what Jesus had said; and they allowed them to take it. Then they brought the colt to Jesus and threw their cloaks on it; and he sat on it. Many people spread their cloaks on the road, and others spread leafy branches that they had cut in the fields. Then those who went ahead and those who followed were shouting,

“Hosanna!

Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord!

Blessed is the coming kingdom of our ancestor David!

Hosanna in the highest heaven!”

Then he entered Jerusalem and went into the temple; and when he had looked around at everything, as it was already late, he went out to Bethany with the twelve. (Mark 11:1-11)

We will examine the text itself before we compare the Mathean version with it.

A Closer Look

1 Καὶ ὅτε ἐγγίζουσιν εἰς Ἱεροσόλυμα εἰς Βηθφαγὴ καὶ Βηθανίαν πρὸς τὸ Ὄρος τῶν Ἐλαιῶν – “When they come near Jerusalem, into Bethphage and Bethany, at the Mount of Olives” (my translation). Mark does not provide us with the proper subject for the present tense ἐγγίζουσιν though it is clear from the immediate context and the previous pericope (10:46-52) that Jesus and the disciples are in view. However, are they the only ones to be considered in the implied subject? Not necessarily. In 10:46 we read, Καὶ ἔρχονται εἰς Ἰεριχώ – “They come into Jericho” (my translation). We are then given a description of the group that then leaves the city of Jericho: καὶ ἐκπορευομένου αὐτοῦ ἀπὸ Ἰεριχὼ καὶ τῶν μαθητῶν αὐτοῦ καὶ ὄχλου ἱκανοῦ – “As Jesus, with his disciples and a large crowd, was leaving from Jericho” (my translation). There the group is clearly comprised of Jesus, the disciples, and ὄχλου ἱκανοῦ and it seems that we should see them in the implied subject of ἐγγίζουσιν as well. [12]

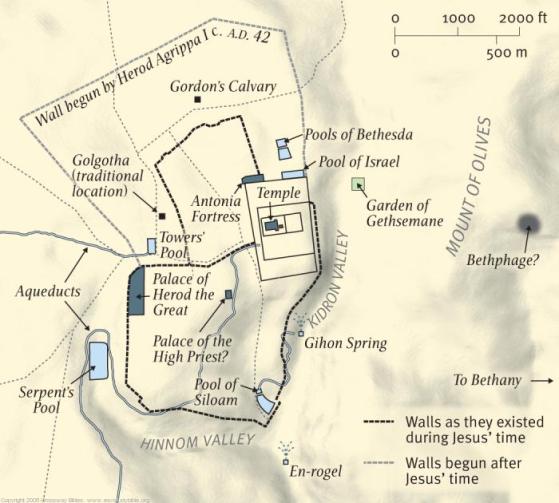

From the city of Jericho, the group travels southwest εἰς Ἱεροσόλυμα – “to Jerusalem” – for the Passover. Mark provides us with a general description of their whereabouts: εἰς Βηθφαγὴ καὶ Βηθανίαν πρὸς τὸ Ὄρος τῶν Ἐλαιῶν. Bethphage seems to have been a town that lay very close to the city of Jerusalem and Bethany was not far from it. For Mark, both towns are near τὸ Ὄρος τῶν Ἐλαιῶν – “the Mount of Olives,” a 2,700 foot high mountain that was to the east of Jerusalem and overlooked the magnificent temple complex.

Then the LORD will go forth and fight against those nations as when he fights on a day of battle. On that day his feet shall stand on the Mount of Olives, which lies before Jerusalem on the east; and the Mount of Olives shall be split in two from east to west by a very wide valley; so that one half of the Mount shall withdraw northward, and the other half southward. (Zechariah 14:3-4)

ἀποστέλλει δύο τῶν μαθητῶν αὐτοῦ, “he sends two of his disciples” (my translation). As we saw with ἐγγίζουσιν, Mark again employs a present tense verb with an implied subject. Clearly Jesus is the one who performs ἀποστέλλει as he alone has the authority to commission them. But who are these two disciples? We are not given their names and are left to speculate. In my estimation, the Markan author leaves their identity a mystery so as not to distract from the important events that are about to transpire in the next few verses.

2 καὶ λέγει αὐτοῖς, Ὑπάγετε εἰς τὴν κώμην τὴν κατέναντι ὑμῶν, “And he says to them, ‘Go into the village that is ahead of you” (my translation). Mark employs yet another historic present verb to communicate the command of Jesus to the two disciples. But to where is Jesus referring when he says τὴν κώμην τὴν κατέναντι ὑμῶν? Only two towns have been named: Bethphage and Bethany. There are no other towns in the near vicinity that could be described as κατέναντι. The immediate context suggests that the group is relatively close to Jerusalem and so the town ahead seems likely to be Bethphage. Bethany could not be described as κατέναντι. [14] However, as was the case with the unidentified disciples, Mark here leaves the town unnamed since the emphasis is not on that specific detail but what will soon unfold when the disciples enter the village.

καὶ εὐθὺς εἰσπορευόμενοι εἰς αὐτὴν εὑρήσετε πῶλον δεδεμένον ἐφ᾽ ὃν οὐδεὶς οὔπω ἀνθρώπων ἐκάθισεν, “And immediately as you enter into it you will find a colt tied, upon which no man has ever sat” (my translation). There is considerable debate over whether the colt has been prearranged by Jesus for this ocassion or if Jesus has foreknowledge of its existence. But that debate typically centers on whether the event took place as described and I’m not interested in that at this time. Suffice it to say, Jesus tells his disciples that εὐθὺς (“immediately”) [15] upon entering the city they will find a colt upon which no one has sat. As Mark employs the double negative οὐδεὶς οὔπω the question naturally arises, Why the emphasis on a colt upon which no one has ever sat?

It must be acknowledged that Mark is drawing themes from Zechariah 9:9, a passage we will look at in our discussion of the Matthean version of the Triumphal Entry. For now we should observe that in that passage the prophet speaks of the king entering Jerusalem “humble and riding on a donkey/on a colt, the foal of a donkey.” Assuming Mark was using the Greek translation of the Old Testament commonly referred to as the LXX, he would have had direct warrant for including a πῶλον in his narrative for the phrase “the foal of a donkey” is rendered in the LXX as πῶλον νέον. And it is not a significant leap to conclude that a πῶλον νέον would be one upon which no one has ever sat.

But there is more. We read in the Hebrew Bible of “the ancient provision that an animal devoted to a sacred purpose must be one that had not been put to ordinary use.” [16] In choosing an animal that had never been put to “ordinary use,” Jesus is strongly suggesting that his use of the animal will be for more than just sitting. Coupled with the fact that it is a πῶλον in line with Zechariah 9:9, Jesus is making his claim to be the messianic king of the Jews. We should also note that the description of the colt being tied up may not be incidental either. It is, perhaps, an allusion to Genesis 49:11 – “Binding his foal to the vine/and his donkey’s colt to the choice vine.” [17]

λύσατε αὐτὸν καὶ φέρετε, “Loose it and bring [to me]” (my translation). Once the two disciples locate the colt, they are to loose it and bring it to Jesus for his use. But what gives Jesus the right to take the animal? What he is commanding his disciples to do is tantamount to borrowing without permission, is it not? The solution to this issue may depend on whether the event was prearranged. Some commentators have suggested that what Jesus is doing is a practice commonly referred to as impressing whereby Jesus takes the animal as is his right to do as king of Israel. [18]

3 καὶ ἐάν τις ὑμῖν εἴπῃ, Τί ποιεῖτε τοῦτο;, “And if anyone says to you, ‘Why are you doing this?'” (my translation). Here Jesus addresses the aforementioned question by offering a probable [19] exchange between the disciples and those observing their untying of the colt. Craig Evans notes that this “question has a biblical ring to it,” [20] alluding to such passages as Exodus 18:14 (“What is this that you are doing for the people?”) and 1 Samuel 2:23 (“Why do you do such things?”) but this seems a stretch.

εἴπατε, Ὁ κύριος αὐτοῦ χρείαν ἔχει, καὶ εὐθὺς αὐτὸν ἀποστέλλει πάλιν ὧδε, “Say, ‘The Lord has need for him, and immediately he will send him again here.'” (my translation). In response to the interrogation of bystanders, the two disciples are to say, “The Lord has need for him.” But there are some issues here that need to be briefly addressed. Specifically, what does Mark (through Jesus) intend by saying that “the Lord has need for him”?

A wide range of opinions can be found on the issue but we should note that nowhere in the Gospel of Mark does Jesus refer to himself as κύριος in an absolute sense. He refers to himself as κύριος…τοῦ σαββάτου, “lord…of the sabbath” (2:28). He is also called κύριος by the Syrophoenician woman though there it is used in the sense of “sir” (7:28). So to what does “the Lord” refer? In keeping with the concept of impressing that we mentioned above, Darrel Bock writes,

Jesus had enough status for this to be done. Thus he is called “the Lord” here, a sign of social respect. The reference to Lord is neither to the owner of the colt or to God. It is simply a note that the need of someone with social rank exists and he will return the colt when done. [21]

This is a plausible view but not one I find I convincing. Earlier we stated that the status of the colt as being one upon which no one has ever sat was a likely reference to the fact that the colt was to be used for a sacred purpose, i.e. bringing Jesus, the messianic king, into the city of Jerusalem. But for the king to be messianic, he must be designated by Yahweh himself and so I think here “the Lord” is referring not to Jesus in any sense but to Yahweh himself. So then the phrase “the Lord has need for him”

asserts that the donkey is needed for God’s service, a bold claim by Jesus for the significance of his own arrival in Jerusalem, but one which is no surprise to those who have learned from Mark that Jesus is bringing in God’s kingdom. [22]

Included with the password Ὁ κύριος αὐτοῦ χρείαν ἔχει is the promise that upon completion of the colt’s task it will be returned immediately to its owner.

4 καὶ ἀπῆλθον καὶ εὗρον πῶλον δεδεμένον πρὸς θύραν ἔξω ἐπὶ τοῦ ἀμφόδου καὶ λύουσιν αὐτόν, “And they left and found the colt, tied to a door, outside in the street, and they loose it” (my translation). The disciples do as Jesus commanded and they find the colt just as Jesus said they would. Mark adds some detail to the narrative with πρὸς θύραν ἔξω ἐπὶ τοῦ ἀμφόδου, perhaps to give some vividness to just where the colt was found in fulfillment of Jesus’ words.

5 καί τινες τῶν ἐκεῖ ἑστηκότων ἔλεγον αὐτοῖς, Τί ποιεῖτε λύοντες τὸν πῶλον;, “And those who were there standing said to them, “What are you doing loosing the colt?” (my translation) As Jesus predicted might happen, bystanders question the disciples actions.

6 οἱ δὲ εἶπαν αὐτοῖς καθὼς εἶπεν ὁ Ἰησοῦς, καὶ ἀφῆκαν αὐτούς, “The disciples said to them just as Jesus had said, and they allowed them” (my translation). The disciples respond to the bystanders καθὼς εἶπεν ὁ Ἰησοῦς – “just as Jesus had said.” The password is accepted by the bystanders and they permit the disciples to leave with the colt.

7 καὶ φέρουσιν τὸν πῶλον πρὸς τὸν Ἰησοῦν καὶ ἐπιβάλλουσιν αὐτῷ τὰ ἱμάτια αὐτῶν, καὶ ἐκάθισεν ἐπ᾽ αὐτόν, “And they bring the colt to Jesus and they lay on it their garments, and he sat upon it” (my translation). In this one sentence the colt is referred to three times: once with the noun τὸν πῶλον and twice with the third person personal pronoun (αὐτῷ and αὐτόν).

The colt is one that had never been sat upon as we saw earlier. And clearly there was no saddle available for it or else the disciples would not have laid their garments upon it. They key point in this verse is ἐκάθισεν ἐπ᾽ αὐτόν. The colt had been described as one upon which no one had ever sat, with Mark employing the verb ἐκάθισεν (11:2). Here Mark uses not only the same verb, καθίζω, but he arranges it so it is in the exact same form. In other words, Mark has emphasized that no man but Jesus sat upon the colt.

8 καὶ πολλοὶ τὰ ἱμάτια αὐτῶν ἔστρωσαν εἰς τὴν ὁδόν, ἄλλοι δὲ στιβάδας κόψαντες ἐκ τῶν ἀγρῶν, “And many people laid their garments upon the road, and others [laid down] leafy branches that they had cut from the fields,” (my translation). Why do the people – invariably the crowd that has followed Jesus from Jericho as well as people from the towns of Bethphage and Bethany – lay down their garments and leafy branches onto the road as he approaches Jerusalem? The immediate contextual clue comes from 11:9-10 where we see his arrival is equated with the “coming kindgom of our ancestor David.” Jesus is the one who enters the city as its king. In keeping with that, the people lay down their garments just as Jehu’s superior officers did when they discovered a prophet had annointed him king of Israel – “Then hurriedly they all took their cloaks and spread them for him on the bare steps” (2 Kings 9:13). There are also elements of a festal celebration that parallels the triumph of Maccabeus over Antiochus Epiphanes – “Therefore, carrying ivy-wreathed wands and beautiful branches and also fronds of palm, they offered hymns of thanksgiving to him who had given success to the purifying of his own holy place” (2 Maccabees 10:7).

Normally those making a pilgrimage to Jerusalem would walk to the city. That Jesus has chosen to ride into the city upon a colt is a sign that he wanted to be noticed. As Bock notes, “Jesus’ entry is purposely provocative. It is loaded with messianic imagery.” [23] This imagery is not lost on the crowd at as we saw with the laying of garments and leafy branches or as we will see in 11:9-10.

9-10 καὶ οἱ προάγοντες καὶ οἱ ἀκολουθοῦντες ἔκραζον, Ὡσαννά·, “And the ones who were going before and the ones accompanying him cried out, ‘Hosanna!'” (my translation) The words that the people cry out as Jesus approaches Jerusalem are adapted from the book of Psalms.

Save us, we beseech you, O LORD!

O LORD, we beseech you, give us success!Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the LORD.

We bless you from the house of the LORD.

(Psalm 118:25-26)

Psalm 118 is part of the fifth book of Psalms (107-150) and is itself the final psalm of the Hallel section (113-118). These psalms were part of the songs of the Levites as worshippers would bring animals to be slaughtered by the priests during Passover. [24] It is no surprise, then, that those accompanying Jesus to the city would have these words in their mind as the time of Passover was drawing near. But why the association with Jesus?

First, Psalm 118 appears to describe a momentous victory by a king over his enemies. He had been surrounded by them and would have faced certain defeat except “in the name of the LORD [he] cut them off” (118:11, 12). Following this victory, the king enters into the temple (118:19) where he can offer a sacrifice of thanksgiving to Yahweh. He is joined then by the people who offer shouts of praise to Yahweh (118:22-25) and by the priests who bless “the one who comes in the name of the LORD” (118:26) and direct the worshippers to the altar (118:27). The king offers his thanks to Yahweh again (118:28) and the psalm concludes with the community responding, “O give thanks to the LORD, for he is good, for his steadfast love endures forever” (118:29). [25]

Second, Jesus is entering Jerusalem from the east where he will then go into the temple (11:11) and the temple will be featured in what follows. The people must have realized that coming from this direction and into that part of the city, one of the first places Jesus would have visited is the temple. Since Jesus is the messianic king, it would make sense for him to enter the temple in accordance with the words of the psalm.

The first word uttered by the crowd is Ὡσαννά, a transliteration of the Hebrew words הֹושִׁ֘יעָ֥ה נָּ֑א from Psalm 118:25 translated in the NRSV as “save us” or, better, “save now.” The words of the people follow a simple pattern:

A- Hosanna!

B – Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord!

B’ – Blessed is the coming of our ancestor David!

A’ – Hosanna in the highest heaven!

Εὐλογημένος ὁ ἐρχόμενος ἐν ὀνόματι κυρίου, “Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord” (my translation). This is straight from Psalm 118:26. There “the one who comes in the name of the LORD” is the conquering king who vanquished his foes with Yahweh’s help. Here it is a reference to Jesus, the king who in his role as Messiah will restore Israel to its former glory.

Εὐλογημένη ἡ ἐρχομένη βασιλεία τοῦ πατρὸς ἡμῶν Δαυίδ, “Blessed is the coming of the kingdom of our father David” (my translation). This section of the people’s words is not part of Psalm 118 and is there own addition. But an addition based on what?

The lineage of Jesus is a theme that is part of the Mathean and Lukan narratives but is decidedly not one shared by Mark. Nevertheless, Jesus’ ties to the legendary king David have been made known in the pericope prior to this one. Bartimaeus, the blind man, called out to Jesus and referred to him as the “Son of David” not once but twice (10:47, 48). How did Bartimaeus know Jesus was of the lineage of David? Or did Bartimaeus simply assume that because Jesus was the Messiah that he was of David’s line? [26]

Whatever the reason, the crowd has 1) heard Jesus referred to as the “Son of David” without any correction from Jesus, 2) observes Jesus riding on a colt in messianic fashion, and 3) lays down their garments as if he were a king coming to the holy city. They believe Jesus is the Davidic messiah and his entrance into the city is “the coming of the kingdom of our father David.”

Ὡσαννὰ ἐν τοῖς ὑψίστοις, “Hosanna in the highest” (my translation). The praise of the people ends with another shout of “Hosanna” with the added magnifier “in the highest.” Their exuberance reaches its zenith.

11 Καὶ εἰσῆλθεν εἰς Ἱεροσόλυμα εἰς τὸ ἱερὸν καὶ περιβλεψάμενος πάντα, “And he entered into Jerusalem into the temple and when he looked around” (my translation). It should be noted that Jesus does not enter the city to fanfare from anyone in Jerusalem. He isn’t greeted by the priests as the king was in Psalm 118. Rather, the whole scene ends anticlimactically.

The entry is not triumphal. Jesus does not enter Jerusalem on a white charger. He does not brandish a series of war trophies, and a train of captives does not trail behind him. In fact, within the week, Roman guards will lead him out of the city as a defeated captive. [27]

Jesus’ first act is to survey the temple. This sets up the events that transpire the following day when he casts out the money changers (11:15-17), an action that gets him noticed by the chief priests who try to find a way to silence him for good (11:18).

ὀψίας ἤδη οὔσης τῆς ὥρας, ἐξῆλθεν εἰς Βηθανίαν μετὰ τῶν δώδεκα, “since it was late in the evening, he left for Bethany with the twelve” (my translation). Having surveyed the temple complex, Jesus leaves the city and heads to Bethany for the night with his disciples. [28]

Summary

The Markan narrative is framed around events that demonstrate Jesus is the Messiah. The story itself is in four parts: the setting (11:1), the acquisition of the colt (11:2-6), the shouts of acclamation from the people as Jesus rides to Jerusalem (11:7-10), and the anticlimactic conclusion (11:11). [29] The fact that the acquisition of the colt takes five of the eleven verses means that its procurement is a central aspect of the narrative. [30] But why? Because of the implicit connection between it and the prophetic utterance found in Zechariah 9:9.

Jesus’ entry into the holy city as its king is meant to be taken by Mark’s readers as an event misunderstood by the people. That is, they anticipated Jesus to ride into the city and sit on the throne of David. But that is not what Jesus in Mark had come to do. The messianic expectations of the disciples (10:35-44) were dampened by Jesus who told them, “For the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many” (10:45). In other words, the mission of the messiah was not to be a king whose underlings wait on him but rather it was to be a king who is willing to offer up his life for his subjects.

The king had come into his city but was not welcomed as king. Mark’s readers would not have been surprised.

THE TRIUMPHAL ENTRY IN THE GOSPEL OF MATTHEW

The Gospel of Matthew has a decidedly “Jewish” feel to it. The main reason for thinking this is that Matthew’s Gospel contains over sixty quotations from the Hebrew Bible and this does not even include allusions to it, more than any of the other Gospels. [31] In so doing, Matthew has revealed that one of his purposes in writing was to convince unbelieving Jews that Jesus was in fact the Jewish messiah. This is particularly obvious by his inclusion of a genealogy at the very beginning of his book. But Matthew was probably also writing to Jewish Christians and was providing them a polemic to counter what Jewish authorites were saying about the fledgling Christian faith.

As stated earlier, Matthew’s Gospel seems to be dependent upon Mark as one its sources. There are a number of key evidences for that proposal that come into play as we investigate Matthew 21:1-11.

- Mark and Matthew share a common narrative.

- In stories shared by Matthew and Mark, the Greek is generally improved upon.

- In stories shared by Matthew and Mark, Matthew typically adds precision of detail or has more concise narrative elements than Mark.

As we compare the Markan and Mathean narratives these three features will be seen clearly. In fact, whereas Mark uses 185 words to tell his version of events, Matthew uses 190 but the additional words are not a product of narrative expansion but of the inclusion of a formulaic prophecy-fulfillment quotation. Here is the story from Matthew 21:1-11 from the NRSV.

When they had come near Jerusalem and had reached Bethphage, at the Mount of Olives, Jesus sent two disciples, saying to them, “Go into the village ahead of you, and immediately you will find a donkey tied, and a colt with her; untie them and bring them to me. If anyone says anything to you, just say this, ‘The Lord needs them.’ And he will send them immediately.” This took place to fulfill what had been spoken through the prophet, saying,

“Tell the daughter of Zion,

Look, your king is coming to you,

humble, and mounted on a donkey,

and on a colt, the foal of a donkey.”The disciples went and did as Jesus had directed them; they brought the donkey and the colt, and put their cloaks on them, and he sat on them. A very large crowd spread their cloaks on the road, and others cut branches from the trees and spread them on the road. The crowds that went ahead of him and that followed were shouting,

“Hosanna to the Son of David!

Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord!

Hosanna in the highest heaven!”When he entered Jerusalem, the whole city was in turmoil, asking, “Who is this?” The crowds were saying, “This is the prophet Jesus from Nazareth in Galilee.”

Examining the Texts

1

|

Mark 11:1 |

Matthew 21:1 |

| Καὶ ὅτε ἐγγίζουσιν | Καὶ ὅτε ἤγγισαν |

| εἰς Ἱεροσόλυμα | εἰς Ἱεροσόλυμα |

| εἰς Βηθφαγὴ καὶ Βηθανίαν | καὶ ἦλθον εἰς Βηθφαγὴ |

| πρὸς τὸ Ὄρος τῶν Ἐλαιῶν | εἰς τὸ Ὄρος τῶν Ἐλαιῶν |

| ἀποστέλλει | τότε Ἰησοῦς ἀπέστειλεν |

| δύο τῶν μαθητῶν αὐτοῦ | δύο μαθητὰς |

A quick glance at the comparison of Mark 11:1 with Matthew 21:1 reveals that while Matthew has maintained the general narrative of the Markan original, he has made changes to verbal forms and eliminated details. Let’s consider the changes.

The opening verb in the Mark narrative was the present tense ἐγγίζουσιν, an example of Mark’s affinity for the historic present. However, Matthew has chosen the aorist form of the verb ἐγγίζω – ἤγγισαν. We can also see that he has changed the present tense ἀποστέλλει into the aorist tense ἀπέστειλεν. These changes are characterstic of Matthew as he frequently eliminates Markan instances of the historic present.

Matthew has also eliminated details. First, whereas Mark mentioned two towns near Jerusalem – Bethphage and Bethany – Matthew refers only to Bethphage. Second, whereas Mark says that Jesus sent δύο τῶν μαθητῶν αὐτοῦ (“two of his disciples”), Matthew eliminates the definite article and the genitive personal pronoun. Matthew has also added a proper subject for the verb ἀπέστειλεν (Ἰησοῦς) while in Mark it is implied by the verbal form.

The elimination of τῶν and αὐτοῦ is not problematic because Matthew provides Ἰησοῦς as the subject and so we know to whom the disciples belong. But it is the elimination of Bethany from his narrative that may be an issue. The Markan narrative left the exact location of Jesus and those following him undetermined. This allowed for the command of Jesus to the disciples to go to the town κατέναντι ὑμῶν (Mark 11:2) to mean Bethphage since Bethany would have been behind them. But Matthew has complicated the story because he has placed them squarely at Bethphage (ἦλθον εἰς Βηθφαγὴ). The only town κατέναντι ὑμῶν (Matthew 21:2) now is Jerusalem! This is not what the Markan narrative had intended and does not fit the narrative as such.

2

|

Mark 11:2 |

Matthew 21:2 |

| καὶ λέγει αὐτοῖς | λέγων αὐτοῖς |

| Ὑπάγετε | Πορεύεσθε |

| εἰς τὴν κώμην τὴν κατέναντι ὑμῶν | εἰς τὴν κώμην τὴν κατέναντι ὑμῶν |

| καὶ εὐθὺς | καὶ εὐθέως |

| εἰσπορευόμενοι εἰς αὐτὴν | Omitted |

| εὑρήσετε | εὑρήσετε |

| πῶλον δεδεμένον | ὄνον δεδεμένην |

| ἐφ᾽ ὃν οὐδεὶς οὔπω ἀνθρώπων ἐκάθισεν | Omitted |

| Not present | καὶ πῶλον μετ᾽ αὐτῆς |

| λύσατε αὐτὸν καὶ φέρετε | λύσαντες ἀγάγετέ μοι. |

Matthean redaction of the Markan narrative continues in 21:2 and it is along the lines of what we saw in 21:1. Matthew has changed verbal forms and, in two instances substituted a different verb. He has also added elements not present in the Markan narrative.

Mark employs the historic present when he writes καὶ λέγει αὐτοῖς. Matthew has changed the verb to the participial λέγων, still in the present tense but more directly tied to the verb ἀπέστειλεν in 21:1 (hence the removal of Mark’s καὶ). The verbal command in Mark was the present imperative Ὑπάγετε. Matthew has changed it to the present imperative Πορεύεσθε. Mark never uses the verb πορεύω in any form save for those instances where it has has been connected to a preposition (i.e. εἰσπορεύομαι or ἐκπορεύομαι). And it is not standard practice for Matthew to replace instances of ὑπάγω in Mark with πορεύω. In fact, under normal circumstances, wherever you find ὑπάγω in Mark, the Matthean counterpart retains the verb. So the question is, Why the change? Is this simply a difference in style? Or is Matthew choosing the more sophisticated πορεύω over the simpler ὑπάγω? I am not sure.

Matthew follows Mark’s εἰς τὴν κώμην τὴν κατέναντι ὑμῶν. But then the narratives begin to depart in their details. In Mark, Jesus tells the disciples that “immediately” as they enter the town they will find a colt, the sense being that as soon as they enter the town they’ll find it. Matthew retains some of that sense but he has omitted entirely εἰσπορευόμενοι εἰς αὐτὴν, perhaps seeing it as irrelevant or even redundant. Instead, he has connected εὐθέως, not to the entering of the town, but to the immediate discovery of what Jesus needs: ὄνον δεδεμένην καὶ πῶλον μετ᾽ αὐτῆς. Mark had but one animal, πῶλον, and the emphasis was on the fact that it was one ἐφ᾽ ὃν οὐδεὶς οὔπω ἀνθρώπων ἐκάθισεν. But this sense is gone entirely. Now there are two animals: a female donkey and her colt.

The final words of 21:2 represent a modification of the Markan narrative. Where we read λύσατε αὐτὸν καὶ φέρετε, Matthew has 1) changed the present imperative λύσατε to the aorist participle λύσαντες, 2) removed the reference to the colt in the pronoun αὐτὸν, and 3) changed the Markan φέρετε to ἀγάγετέ μοι.

3

|

Mark 11:3 |

Matthew 21:3 |

| καὶ ἐάν τις ὑμῖν εἴπῃ | καὶ ἐάν τις ὑμῖν εἴπῃ |

| Τί ποιεῖτε τοῦτο; | Τι |

| εἴπατε | ἐρεῖτε ὅτι |

| Ὁ κύριος αὐτοῦ χρείαν ἔχει | Ὁ κύριος αὐτῶν χρείαν ἔχει |

| καὶ εὐθὺς | εὐθὺς δὲ |

| αὐτὸν ἀποστέλλει πάλιν ὧδε | ἀποστελεῖ αὐτούς |

Matthean modification continues except in 21:3 it comes in the forms of 1) an abbreviation, 2) changes in verb forms, 3) a modification of a pronoun, and 4) a change in meaning.

In Mark 11:3, Jesus tells the disciples how to respond ἐάν τις ὑμῖν εἴπῃ, Τί ποιεῖτε τοῦτο; – “If anyone says to you, ‘Why are you doing this?'” But as the comparison shows, while Matthew retains καὶ ἐάν τις ὑμῖν εἴπῃ he has eliminated the question Τί ποιεῖτε τοῦτο; in favor of Τι. So then in Matthew Jesus says, “If anyone says anything to you.” The response of the disciples to this is the same in Matthew as it is in Mark, save for the the pluralization of the personal pronoun αὐτοῦ to αὐτῶν to accomodate the second animal.

It cannot go without notice that the Markan εἴπατε has been changed in Matthew to ἐρεῖτε ὅτι. While ὅτι is just a way to mark direct discourse, it is the change in verb form that is so interesting. εἴπατε is the aorist form of λέγω while ἐρεῖτε is the future imperative of λέγω. Grant Osborne writes that ἐρεῖτε “is a case of a future with imperatival force, normally used of divine commands such as in the Ten Commandments and here to portray Jesus’ sovereign command of the situation.” [32] Given Jesus issuing of commands (i.e. verbs in the imperative), the use of the future tense implies that, for Matthew, Jesus has some foreknowledge of the events that will take place when the disciples go to get the animals.

There is a substantial change of meaning in how Matthew has modified Mark’s καὶ εὐθὺς αὐτὸν ἀποστέλλει πάλιν ὧδε, “And immediately he will send him again here.” There it is part of Jesus’ words to the disciples as to what they should say to anyone who asks him why they are taking the colt, the implication being that once Jesus has finished using the colt he will return it to its owner. The Matthean modification appears to be very similiar to the Markan narrative but he has eliminated πάλιν ὧδε and therefore changed the meaning: εὐθὺς δὲ ἀποστελεῖ αὐτούς, “And immediately he will send them.” Now the implied subject of ἀποστελεῖ is not Jesus but the owner of the two animals.

4 Τοῦτο δὲ γέγονεν ἵνα πληρωθῇ τὸ ῥηθὲν διὰ τοῦ προφήτου λέγοντος, ” This happened in order to fulfill the word spoken through the prophet,” (my translation). This is one of the over sixty formulaic prophecy-fulfillment quotations common to Matthew and it is where Matthew departs from Mark decidedly. This specific quotation is composite, that is Matthew is drawing from the words of two prophets: Isaiah and Zechariah. The bulk of the citation is Zecharian, as we will see.

5 Εἴπατε τῇ θυγατρὶ Σιών, “Say to Daughter Zion” (my translation). The first line of Matthew’s citation comes from the book of Isaiah where we read,

The LORD has proclaimed

to the end of the earth:

Say to daughter Zion,

“See, your salvation comes;

his reward is with him,

and his recompense before him.”

(Isaiah 62:11)

But Matthew hasn’t taken these words from the Hebrew text. Rather, as he is wont to do, he has borrowed the words directly from the LXX where we read Εἴπατε τῇ θυγατρὶ Σιων, “Say to daughter Zion.” Though in context Isaiah 62:10-12 is about the return of exiles to the city of Jerusalem [33], Matthew clearly sees more going on. And the reason for this may have to do with how the LXX renders the line after “Say to daughter Zion.” Instead of “See, your salvation comes,” the LXX reads Ιδού σοι ὁ σωτὴρ παραγίνεται, “See, the savior comes to you.” The parallel between the LXX of Isaiah 62:11 and Zechariah 9:9 was evidence for Matthew that ὁ σωτὴρ and ὁ βασιλεύς are one in the same person: Jesus.

Ἰδοὺ ὁ βασιλεύς σου ἔρχεταί σοι, “See, your king comes to you” (my translation). Now begins Matthew’s citation of the Zecharian passage. But as we did with the Markan passages, we should compare the Zecharian original with the Matthean version.

|

Zechariah 9:9 |

Matthew 21:5 (portion from Zechariah) |

| Χαῖρε σφόδρα, θύγατερ Σιων | Omitted |

| κήρυσσε, θύγατερ Ιερουσαλημ | Omitted |

| ἰδοὺ ὁ βασιλεύς σου ἔρχεταί σοι | Ἰδοὺ ὁ βασιλεύς σου ἔρχεταί σοι |

| δίκαιος καὶ σῴζων αὐτός | Omitted |

| πραῢς | πραῢς |

| καὶ ἐπιβεβηκὼς ἐπὶ ὑποζύγιον | καὶ ἐπιβεβηκὼς ἐπὶ ὄνον |

| καὶ πῶλον νέον | καὶ ἐπὶ πῶλον υἱὸν ὑποζυγίου |

Matthew has modified the passage from Zechariah in a number of ways that we will briefly consider.

First, Matthew has omitted entirely Χαῖρε σφόδρα, θύγατερ Σιων (“Rejoice exceedingly, daughter Zion”), κήρυσσε, θύγατερ Ιερουσαλημ (“Proclaim, daughter Jerusalem”), and δίκαιος καὶ σῴζων αὐτός (“righteous and saving is he”). Εἴπατε τῇ θυγατρὶ Σιων replaces the first two lines though it is quite clear Matthew could have never bothered with the citation from Isaiah and retained the Zecharian words. But since Matthew is connecting both the Isaian words with what we read in Zechariah, he has adjusted accordingly. He has also removed δίκαιος καὶ σῴζων αὐτός to abbreviate the text, perhaps in a bid to keep the focus on the manner in which the king comes rather than his specific qualities. Remember, the passage serves as justification for the additional beast not found in Mark.

Second, Matthew has changed the wording of the LXX to suit his purposes. Where the LXX read καὶ ἐπιβεβηκὼς ἐπὶ ὑποζύγιον, Matthew has modified it to read καὶ ἐπιβεβηκὼς ἐπὶ ὄνον. The reason for the change is clear: in Matthew’s version of the Triumphal Entry Jesus has requested the disciples locate a female donkey. The LXX’s ὑποζύγιον is neuter and the Hebrew text upon which it is based reads חמור, a male donkey. We can also see that Matthew has changed καὶ πῶλον νέον to καὶ ἐπὶ πῶλον υἱὸν ὑποζυγίου. This is an interesting alteration. For starters, πῶλον νέον could reflect the Markan passage’s πῶλον δεδεμένον ἐφ᾽ ὃν οὐδεὶς οὔπω ἀνθρώπων ἐκάθισεν. But Matthew has changed it to reflect the Hebrew original: על־עיר בן־אתנות. Matthew’s usage of υἱὸν ὑποζυγίου is intended to reflect that בן־אתנות clearly refers to the colt belonging to a female donkey.

Third, Matthew has inserted ἐπὶ in the parallel line καὶ ἐπὶ πῶλον υἱὸν ὑποζυγίου whereas in Zechariah it is omitted. In this way, Matthew reflects more accurately the Hebrew original which has the preposition על before both חמור and עיר. By adding ἐπὶ, Matthew is providing justification for Jesus’ riding on both animals as we will see in 21:7.

6 πορευθέντες δὲ οἱ μαθηταὶ καὶ ποιήσαντες καθὼς συνέταξεν αὐτοῖς ὁ Ἰησοῦς, “The disciples went and did just as Jesus had directed them.” Matthew has omitted entirely the words from Mark 11:4-6. Perhaps Matthew saw such information as redundant given the outcome of the day’s events.

7

|

Mark 11:7 |

Matthew 21:7 |

| καὶ φέρουσιν | ἤγαγον |

| τὸν πῶλον πρὸς τὸν Ἰησοῦν | τὴν ὄνον καὶ τὸν πῶλον |

| καὶ ἐπιβάλλουσιν αὐτῷ τὰ ἱμάτια αὐτῶν | καὶ ἐπέθηκαν ἐπ᾽ αὐτῶν τὰ ἱμάτια |

| καὶ ἐκάθισεν ἐπ᾽ αὐτόν | καὶ ἐπεκάθισεν ἐπάνω αὐτῶν |

Matthew has changed Mark’s historic present φέρουσιν to the aorist ἤγαγον (“they brought”). He has also changed Mark’s ἐπιβάλλουσιν to ἐπέθηκαν (“they put”) and his ἐκάθισεν to ἐπεκάθισεν, though the change is simply the addition of the preposition ἐπὶ to the verb stem. (The tense of the verb remains the same.) The remaining changes involve the animals.

First, τὸν πῶλον in Mark becomes τὴν ὄνον καὶ τὸν πῶλον. Second, because of the additional animal, Mark’s ἐπιβάλλουσιν αὐτῷ τὰ ἱμάτια αὐτῶν becomes ἐπέθηκαν ἐπ᾽ αὐτῶν τὰ ἱμάτια, with the singular αὐτῷ becoming the plural αὐτῶν. Third, Mark’s ἐκάθισεν ἐπ᾽ αὐτόν becomes ἐπεκάθισεν ἐπάνω αὐτῶν, with the singular αὐτόν becoming the plural αὐτῶν. Matthew is clearly reflecting Mark’s version, modifying it to eliminate verbal forms he does not care for as well as unnecessary details. But he retained the essential form of the text and has modified it to accomodate the additional animal. We will examine this further in the section below entitled “One Helluva Ride: One Beast or Two?”

8

|

Mark 11:8 |

Matthew 21:8 |

| καὶ πολλοὶ | ὁ δὲ πλεῖστος ὄχλος |

| τὰ ἱμάτια αὐτῶν ἔστρωσαν εἰς τὴν ὁδόν | ἔστρωσαν ἑαυτῶν τὰ ἱμάτια ἐν τῇ ὁδῷ |

| ἄλλοι δὲ | ἄλλοι δὲ |

| στιβάδας κόψαντες ἐκ τῶν ἀγρῶν | ἔκοπτον κλάδους ἀπὸ τῶν δένδρων καὶ ἐστρώννυον ἐν τῇ ὁδῷ |

The Markan πολλοὶ has become the Matthean πλεῖστος ὄχλος, “a huge crowd.” But Matthew has retained both the verb (ἔστρωσαν) as well as the items placed on the road (τὰ ἱμάτια). He has replaced αὐτῶν with ἑαυτῶν (“their own”) and changed the Markan εἰς plus the accusative τὴν ὁδόν for ἐν plus the dative τῇ ὁδῷ.

One significant change between the Markan and Matthean versions is that whereas Mark employs the generic στιβάδας κόψαντες ἐκ τῶν ἀγρῶν to describe the branches that the people placed on the road, Matthew chose κλάδους ἀπὸ τῶν δένδρων, “branches from the trees.” However, this seems to be nothing more than an instance of Matthean clarification, choosing a more specific term to replace a generic Markan one.

9

|

Mark 11:9-10 |

Matthew 21:9 |

| καὶ οἱ προάγοντες | οἱ δὲ ὄχλοι οἱ προάγοντες |

| καὶ οἱ ἀκολουθοῦντες | καὶ οἱ ἀκολουθοῦντες |

| ἔκραζον | ἔκραζον λέγοντες |

| Ὡσαννά· | Ὡσαννὰ τῷ υἱῷ Δαυίδ |

| Εὐλογημένος ὁ ἐρχόμενος ἐν ὀνόματι κυρίου | Εὐλογημένος ὁ ἐρχόμενος ἐν ὀνόματι κυρίου |

| Εὐλογημένη ἡ ἐρχομένη βασιλεία τοῦ πατρὸς ἡμῶν Δαυίδ | Omitted |

| Ὡσαννὰ ἐν τοῖς ὑψίστοις | Ὡσαννὰ ἐν τοῖς ὑψίστοις |

Matthew follows Mark generally until the shouts of the people beginning with Ὡσαννὰ τῷ υἱῷ Δαυίδ. He retains Mark’s οἱ προάγοντες and καὶ οἱ ἀκολουθοῦντες and only adds λέγοντες to the Markan ἔκραζον.

When we get to the shouts of acclamation from the people, we begin to see some changes. In particular, Matthew has abbreviated Mark by tagging τῷ υἱῷ Δαυίδ (“to the son of David”) to the first Ὡσαννὰ. This has made the Markan Εὐλογημένη ἡ ἐρχομένη βασιλεία τοῦ πατρὸς ἡμῶν Δαυίδ unnecessary and Matthew has omitted it.

10 καὶ εἰσελθόντος αὐτοῦ εἰς Ἱεροσόλυμα ἐσείσθη πᾶσα ἡ πόλις λέγουσα, Τίς ἐστιν οὗτος; “And when he entered Jerusalem the whole city was shaken saying, ‘Who is this?'” (my translation) There is a contrast made in Matthew’s Gospel between those who were accompanying Jesus and the people of Jerusalem. The former know who he is: he is “the son of David” (21:9). But the people of Jerusalem have seemingly never seen Jesus before and have no idea from where the excitement about him comes. They are likely troubled by the messianic title being attributed to him by the people and are concerned that this could lead to another disastrous military confrontation with Rome. [34]

11 οἱ δὲ ὄχλοι ἔλεγον, Οὗτός ἐστιν ὁ προφήτης Ἰησοῦς ὁ ἀπὸ Ναζαρὲθ τῆς Γαλιλαίας, “And the crowd said, ‘This is the prophet Jesus of Nazareth in Gaililee” (my translation). Those who had accompanied Jesus tell the inhabitants of Jerusalem that Jesus is a prophet from Nazareth, a town in Galilee. This does not mean that the crowd saw Jesus merely as a prophet. The term carried with it a great deal of honor and respect [35] though there is some debate as to whether the term is a veiled reference for the eschatological Moses-like prophet of Deuteronomy 18:15. [36] Whatever the case may be, the crowd explains to the city’s citizens that Jesus is not simply an ordinary man.

Summary

The Matthean version of the Triumphal Entry ends differently than that of Mark’s. In Mark, the episode ends with Jesus entering the temple complex, surveying it, and, because it was late in the day, returning to Bethany for the night. This sets up for the activities of the following chapters. But in Matthew, the scene ends with the city in turmoil and its inhabitants asking who the man on the animals was. In fact, the two accounts are irreconcilable in their chronology.

|

Mark Order of Events |

Matthew Order of Events |

| Jesus enters Jerusalem (11:11) | Jesus enters Jerusalem (21:10) |

| Jesus surveys the temple complex (11:11) | Omitted |

| Jesus leaves for Bethany (11:11) | Jesus casts out money changers (21:12-16) |

| Jesus leaves from Bethany (11:12) | Jesus leaves for Bethany (21:17) |

| Jesus curses the fig tree (11:13-14) | Jesus leaves from Bethany (21:18) |

| Jesus arrives in Jerusalem (11:15) | Jesus curses the fig tree (21:19-22) |

| Jesus casts out money changers (11:15-17) | Jesus enters the temple again (21:23) |

As we saw, the Matthean author has changed Mark’s story in subtle ways – particularly the omission of certain “redundant” details and the changing of verb tense from present to aorist – and in not-so-subtle ways. The most obvious and important changes can be seen in his inclusion of an animal in addition to the colt upon which Jesus rode and the formulaic prophecy-fulfillment motif in 21:4-5. These two important changes are the topic of the next section.

ONE HELLUVA RIDE: ONE BEAST OR TWO?

As stated in my introduction, the main thesis of this post is that Matthew includes two animals instead of one because of his desire to portray Jesus as literally fulfilling Zecharian prophecy. The first section of this post – “The Triumphal Entry in the Gospel of Mark” – offered a brief overview of Mark 11:1-11 as well as commentary. We saw how in Mark Jesus comissioned two of his disciples to a nearby city to procure a colt upon which no man had ever sat. This colt he rode upon on his journey to Jerusalem. And while the imagery of Zechariah 9:9 was lurking in the background, Mark does not attempt to explicitly connect the event to prophetic utterance. The second section of this post – “The Triumphal Entry in the Gospel of Matthew” – compared the Matthean version with the Markan.

It is quite clear by the overlapping use of terms and the sequence of events that Matthew is dependent upon Mark for his own version. But whereas Mark has focused on the intricate details of the events, Matthew focuses on the overarching meaning of it all. This is clearly seen in both the prophecy-fulfillment motif and in the ending of the pericope where the citizens of Jerusalem react to Jesus’ entry into their city and the accompanying crowd’s response to the question of Jesus’ identity. As already stated, Mark’s implicit dependence upon the Zecharian prophecy is made explicit by Matthew as he directly quotes the post-exilic prophet.

One Beast or Two?

Of the four Gospel accounts of the Triumphal Entry, Matthew is the only one to have two animals rather than one. Since he is using Mark’s general framework for his own story, Matthew altered the Markan text to accomodate the extra animal. Let’s look at a side-by-side comparison to see.

| Mark | Matthew |

| 2: εὑρήσετε πῶλον δεδεμένον | 2: εὑρήσετε ὄνον δεδεμένην καὶ πῶλον |

| 2: λύσατε αὐτὸν καὶ φέρετε | 2: λύσαντες ἀγάγετέ μοι |

| 3: Ὁ κύριος αὐτοῦ χρείαν ἔχει | 3: Ὁ κύριος αὐτῶν χρείαν ἔχει |

| 3: καὶ εὐθὺς αὐτὸν ἀποστέλλει πάλιν ὧδε | 3: εὐθὺς δὲ ἀποστελεῖ αὐτούς |

| 4: καὶ εὗρον πῶλον | omitted |

| 7: φέρουσιν τὸν πῶλον | 7: ἤγαγον τὴν ὄνον καὶ τὸν πῶλον |

| 7: καὶ ἐπιβάλλουσιν αὐτῷ τὰ ἱμάτια αὐτῶν | 7: καὶ ἐπέθηκαν ἐπ᾽ αὐτῶν τὰ ἱμάτια |

| 7: καὶ ἐκάθισεν ἐπ᾽ αὐτόν | 7: καὶ ἐπεκάθισεν ἐπάνω αὐτῶν |

Apart from some verb changes and the omission of the discovery of the animal (Mark 11:4), Matthew has retained the Markan form and our interpretation of it should follow from that.

Mark 11:2 and Matthew 21:2

In the Markan narrative, Jesus sends the two disciples to a nearby village where he tells them they will find a colt tied. Mark uses a future tense verb (εὑρήσετε) with the accusative direct object (πῶλον δεδεμένον). In the Matthean narrative, Jesus sends the two disciples to a nearby village where he tells them they will find a donkey tied and a colt with her. Matthew uses the exact same future tense verb (εὑρήσετε) with two accusative direct objects (ὄνον δεδεμένην καὶ πῶλον).

We also see that in the Markan narrative the disciples are to loose the colt and bring it to Jesus (literally, “Loose him and bring”). The construction in Mark is aorist imperative verb (λύσατε) plus an accusative direct object (αὐτὸν) as well as a present imperative verb (φέρετε) that functions elliptically (i.e. the implied direct object is the colt). In the Matthean narrative we see similar constructions though with the common Matthean alterations. Matthew also uses an aorist imperative form of λύω (λύσαντες) though it is in participial form and is used elliptically. Matthew also chooses a different verb than Mark to communicate the command to bring the animal to Jesus. Mark used the present imperative of φέρω whereas Matthew changes both the tense of the verb from present to aorist as well as the verb itself from φέρω to ἄγω (ἀγάγετέ). Matthew has also inserted an indirect object (μοι).

Mark 11:3 and Matthew 21:3

In the Markan narrative, Jesus instructs the disciples on what to say should any bystanders question why they are untying the colt: “The Lord needs it.” Mark’s construction is subject (Ὁ κύριος) plus the genitive complement (αὐτοῦ) plus the the idomatic χρείαν ἔχει (“has need”). Matthew has retained exactly the Markan form except where Mark has the singular genitive complement αὐτοῦ, Matthew has the plural genitive complement αὐτῶν to reflect the additional animal.

We also see that the Markan καὶ εὐθὺς αὐτὸν ἀποστέλλει, where the direct object of the present tense ἀποστέλλει is the colt (αὐτὸν), has been retained in Matthew where the direct objects of the same Markan verb (in the future tense this time) are the donkey and the colt (αὐτούς).

Mark 11:7 and Matthew 21:7

In the Markan narrative, 11:7 is in three parts. First, the disciples bring the colt (τὸν πῶλον) to Jesus. Mark uses the same Greek verb (φέρουσιν from φέρω) that he did in Jesus’ command to the disciples in 11:2. Second, the disciples place upon the colt (αὐτῷ) their garments (τὰ ἱμάτια αὐτῶν). Finally, Jesus sits upon the colt (ἐπ᾽ αὐτόν).

In the Matthean narrative, 21:7 is in three parts as well, mirroring the Markan narrative. First, the disciples bring the donkey and the colt (τὴν ὄνον καὶ τὸν πῶλον) to Jesus. Matthew uses the same Greek verb (ἤγαγον from ἄγω) that he did in Jesus’ command to the disciples in 21:2. Second, the disciples place upon the donkey and the colt (αὐτῶν) their garments (τὰ ἱμάτια). Finally, Jesus sits upon “them” (ἐπάνω αὐτῶν).

What Does Matthew Mean by ἐπεκάθισεν ἐπάνω αὐτῶν?

In its rendering of Matthew 21:7, the NRSV reads, “They brought the donkey and the colt, and put their cloaks on them, and he sat on them.” Similarly, the English Standard Version reads, “They brought the donkey and the colt and put on them their cloaks, and he sat on them.” Both the NRSV and the ESV are more faithful to the wording of the Greek text.

Contrast this with how the New International Version translates Matthew 21:7 – “They brought the donkey and the colt and placed their cloaks on them for Jesus to sit on.” The New American Standard Bible reads, “And [they] brought the donkey and the colt, and laid their coats on them; and He sat on the coats.” Both the NIV and the NASB have forced an interpretation upon the text. But it is easy to see why they did so.

Matthew’s ἐπεκάθισεν ἐπάνω αὐτῶν seems slightly ambiguous. The question is, What is the antecedent of the genitive αὐτῶν? In his excellent commentary on Matthew’s Gospel, R. T. France translated 21:7 similar to the NIV’s rendering: “They brought the donkey and the foal, and put cloths on them for Jesus to sit on.” [37] He then writes in a footnote, “Common sense rather than Greek syntax requires that the ‘them’ must refer to the cloths (the most recent antecedent) rather than the two animals. My free translation attempts to avoid the unhelpful impression of a circus act.” [38] But is avoiding the “impression of a circus act” Matthew’s concern? I do not believe that it is. The reason has to do with how Matthew uses Zechariah 9:9.

Matthew and Zechariah

As we have already noted, Matthew is fond of the formulaic prophecy-fulfillment motif. And in the Passion Narrative, utterances from Zechariah are used three times: here in chapter 21, in 26:31, and again in 27:9. [39] In 26:31, Jesus tells the disciples that they would all desert him soon in fulfillment of Zechariah 13:7 which reads,

Awake, O sword, against my shepherd,

against the man who is my associate,” says the LORD of hosts.

Strike the shepherd, that the sheep may be scattered;

I will turn my hand against the little ones.

Jesus singles out the third line – “Strike the shepherd, that the sheep may be scattered” – as the prophetic proof that this would happen. Jesus then speaks of Peter’s coming denial of him as an example of this scattering of his sheep. In other words, the disciples would literally be scattered about away from Jesus, their shepherd. In 27:9, which is a composite quotation like that of 21:5, Matthew sees Judas returning thirty pieces of silver which was then used to purchase a potter’s field to be a fulfillment of Zechariah 11:13 – “Then the LORD said to me, ‘Throw it into the treasury’ – this lordly price at which I was valued by them. So I took the thirty shekels of silver and threw them into the treasury in the house of the LORD.” In other words, Judas literally fulfilled the prophetic utterance.

Similarly, Matthew has included a donkey with the Markan colt because Jesus must literally fulfill the prophetic utterance of Zechariah 9:9, the implicit scriptural motif in the Markan narrative. Let’s look at Zechariah 9:9 once more.

Rejoice greatly, O daughter Zion!

Shout aloud, O daughter Jerusalem!

Lo, your king comes to you;

triumphant and victorious is he,

humble and riding on a donkey,

and on a colt, the foal of a donkey.

The words of the prophets often take the form of poetry and Zechariah 9:9 is no exception. In the case of Zechariah 9:9, we see two instances of Hebrew parallelism, specifically synonymous parallelism. In synonymous parallelism, the writer will make a statement and then make another statement which effectively reiterates the first. [40] For example, the first two lines of Zechariah 9:9 say essentially the same thing. “Rejoice greatly” is synonymous with “shout aloud,” and “daughter Zion” is synonymous with “daughter Jerusalem.” The same thing is going on with the final two lines where the triumphant king is described as “riding on a donkey” and as riding “on a colt, the foal of a donkey.” In other words, a colt, being the “foal of a donkey” is a donkey. This is syonymous parallelism at work. [41]

But why does Matthew not pick up on this? Is he unaware of the parallelism? Probably not. Instead, it seems that Matthew is using a hermenutic of “rabbinic Judaism of the first century [that] assumed that Scripture contained no parallelism.” [42] Instead of recognizing that the second line contributes specificity to the first, Matthew interpreted the two lines as being speaking of distinct entities. David Instone-Brewer writes that

in Matthew’s mind it was obvious that Jesus’ action was fulfilling the prophecy of Zechariah, but it was equally obvious that the prophecy spoke about two animals. He would have felt able to extend the account of Jesus’ entrance by using the information he found in Zechariah. This was Scripture, after all, and therefore it was correct in every detail. Zechariah’s witness was more weighty than that of Mark, so if Zechariah said there were two animals, it was safe for Matthew to record the fact. [43]

So then Matthew is not ignorant of the parallelism. It simply wasn’t his hermenutic. By including two animals in the narrative, Matthew attempted “to show with what literal detail Jesus fulfilled the prophecy….Matthew was not offering an unusual hermeneutic; his contemporaries regularly read more into a text than it required when it suited their purposes to do so.” [44] Therefore, because the king of Zechariah 9:9 rode upon a donkey and a colt, Jesus, the king about whom Zechariah wrote, must have also ridden upon a donkey and a colt.

But that isn’t all. Matthew follows Mark directly. It would seem very odd for Matthew to reiterate the Markan language of 21:7 essentially verbatim in every instance except the last line. Remember, Matthew had to turn the singular pronouns used by Mark into plurals so he could include the additional animal.

|

Mark 11:7 (NRSV) |

Matthew 21:7 (NRSV) |

| Then they brought the colt to Jesus | They brought the donkey and the colt, |

| and threw their cloaks on it; | and put their cloaks on them, |

| and he sat on it. | and he sat on them. |

Are we to believe that Matthew intended to parallel the meaning of Mark in each line except the final? This seems highly unlikely.

Summary

Matthew used Mark’s general framework throughout his version and we should take that seriously. Couple that with how Matthew likely viewed the parallelism in the Hebrew Bible, it seems unavoidable that he intended for the reader to see Jesus as actually riding upon two animals, regardless of the objection of France that such a feat would be a “circus act.” If the stories in the Gospels represent a historical memory of Jesus actual pilgrimage to Jerusalem, then without a doubt Jesus would have only ridden one animal. But that is not the interest of Matthew the story-teller. For Matthew, Jesus is the fulfillment of ancient prophecy and he does so in literal detail, including the riding of two animals to Jerusalem. [45]

A WORD ON THE TRIUMPHAL ENTRY IN THE GOSPEL OF LUKE

AND THE GOSPEL OF JOHN

We should also briefly comment on the other two versions of the Triumphal Entry found in the Gospels of Luke and John.

The Gospel of Luke

The story of the Triumphal Entry in Luke can be found in 19:28-40. Like Matthew’s version, it too is clearly dependent upon Mark’s Gospel. But whereas Matthew has two animals, Luke keeps with just the colt (19:30). Luke also does not abbreviate Mark’s account as Matthew had though he does choose different verbs and verbal forms than Mark had employed. [46] Of particular interest is that the allusion to Zechariah remains just that in Luke’s Gospel. There is no explicit reference to it at all.

The Gospel of John

The story of the Triumphal Entry in John can be found in 12:12-19. It is unlikely that John had any of the Synoptic Gospels with which to work and so his version represents an independent version of the story. It lacks the command from Jesus to the disciples to go into the nearby city and find a colt (or donkey and colt) tied and to bring it to him. Instead, John tells us that “Jesus found a young donkey and sat on it” (12:14). John then connects Jesus’ riding upon a donkey into the city with Zechariah 9:9, just as Matthew did. But whereas Matthew saw Jesus literally fulfilling the prophecy by including two animals, John sees Jesus as only riding upon one.

Do not be afraid, daughter of Zion.

Look, your king is coming,

sitting on a donkey’s colt!

(John 12:15)

This is significant for our understanding of the Matthean citation of Zechariah 9:9. In John’s citation, we see that he has altered and abbreviated the LXX of Zechariah 9:9. And he has understood the parallel structure of “riding upon a donkey/and upon a colt, the foal of a donkey” to mean one animal: “a donkey’s colt.”

That John sees one animal using the same passage from the Hebrew Bible wherein Matthew sees two animals is quite telling. It means that Matthew really did intend for Jesus to be seen as riding upon two animals into the city.

CONCLUSION

This has been a wholly inadequate analysis of the texts found in Mark and Matthew. It is suggested that the reader explore the works mentioned in the endnotes to form their own view as well as reading the texts themselves which is by far the most important task of all.

It is my opinion that the thesis that Matthew includes two animals instead of one because of his desire to portray Jesus as literally fulfilling Zecharian prophecy has been vindicated. We have seen that Matthew alters the Markan text to accomodate a second animal even though he retains the general framework of Mark. We also saw that his view of prophecy fulfillment was likely in line with rabbinic hermenutics of the first century which saw synonymous parallelism as a subversion of scriptural authority since it implied redundancy and, therefore, an imperfection on God’s part.

ENDNOTES

[1] For example, see Keith F. Nickle, The Synoptic Gospels (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001); Bart Ehrman, The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings (Oxford University Press, 2016), 120-128; G.M. Styler, “Synoptic Problem,” in Bruce M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan, editors, The Oxford Companion to the Bible (Oxford University Press, 1993), 724-727; L. Michael White, Scripting Jesus: The Gospels in Rewrite (New York, NY: HarperOne, 2010), 10-13.

[2] Martin Kahler, The So-Called Historical Jesus and the Historic Biblical Christ, Carl E. Braaten, translator (Philadelphia, PA: Westerminster Press, 1975), 80, quoted in Nickle, 72.

[3] Robert A. Guelich, Mark 1 – 8:26, WBC (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 1989), xxxvi. The late New Testament scholar R.T. France saw in the Markan story a “drama in three acts” wherein, following the heading (1:1) and prologue (1:2-13), there are three acts centered in various geographical locales: in Galilee (1:14-8:21), on the way to Jerusalem (8:22-10:52), and at Jerusalem (11:1-16:8). However, France offers the caveat that “Mark did not write a text in sections, but a single flowing narrative, and that any structure we discern is a matter of our reading of the text, not of Mark’s direction.” (France, The Gospel of Mark, NIGTC [Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002], 13-14.)

David Hawkin structures Mark around the identity of Jesus. Mark 1:1-8:21 asks the question, “Who is Jesus?” while 8:22-16:8 answers that question. (Hawkin, “The Symbolism and Structure of the Marcan Redaction,” Evangelical Quarterly 49.2 [June-July 1977], 108-110.

[4] Guelich writes on 3:22, “Whereas ‘Jerusalem’ as the center of Jewish legal authority…may give weight to the delegation, it clearly represents in Mark a place of hostility for Jesus, the place of his death and itself destined for destruction.” (Guelich, 174) William Hendricksen offers his own colorful take on the scribes of 3:22:

Scribes had been sent to spy on Jesus. Down from Jerusalem – elevation about 2400 feet above sea level – they came to Galilee, the Sea of Galilee being about 600 feet below sea level. However, when these law experts, probably delegated by the Sanhedrin, descended toward Capernaum, they must have considered their descent ideological – Jerusalem being the citadel of Jewish orthodoxy – fully as much as merely physical. (William Hendricksen, Mark, NTC [Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 1975], 134.)

[5] Elizabeth Malbon has a helpful list of places where the disciples and the crowd are mentioned in Mark. See her In the Company of Jesus: Characters in Mark’s Gospel (Lousville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2000), 229-232.

[6] Marcus Borg offers a condensed definition of the “Messianic Secret” when he writes,

Mark does not portray Jesus as publicly proclaiming his identity as “Son of God” or “Messiah.” Of course, Mark affirms that Jesus is both, but he does not present the titles as part of the message of Jesus himself. The two affirmations of an exceptional status for Jesus are in private and not part of Jesus’ public teaching (8.27-30; 14.61-62). According to Mark, Jesus is Messiah and Son of God – but this was a secret during Jesus’s lifetime (a feature commonly called the “messianic secret”). (Marcus Borg, Evolution of the Word: The New Testament in the Order the Books Were Written [New York, NY: HarperOne, 2012], 151.

See also Lamar Williamson, Jr., Mark, Interpretation Commentary Series (Louisville, KY: John Knox Press, 1983), 12-13; Nickle, 81-82; Harald Riesenfeld, “Messianic Secret,” in Metzger and Coogan, 514-515; Ehrman, The New Testament, 112.

[7] On Mark’s sources, see Guelich, xxxii-xxxv.

[8] France, The Gospel of Mark, 17.

[9] In Mark, the conjunction καί begins about sixty-four percent of all his sentences. Whereas in Enlglish it seems to make the narrative disjointed, it is in fact a sign of continuity in Mark, a way of connecting narratives. For more, see Rodney Decker, Mark 1-8: A Handbook on the Greek Text (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2014), xxvi-xxvii.

[10] Daniel Wallace writes that the historic present “occurs mostly in less educated writers as a function of colloquial, vivid speech. More literary authors, as well as those who aspire to a distanced historical reporting, tend to avoid it.” Per Wallace, the historic present occurs in John 162 times, Mark 151 times, Matthew 93 times “at most,” and Luke 11 times. “The historical present is preeminently the story-teller’s tool and as such occurs exclusively (or almost exclusively) in narrative literature.” (Daniel Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics: An Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament [Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1996], 528.)

I am skeptical of Wallace’s claim that “less educated writers” employ the historic present. For a long time I had assumed Mark to be rather simple and even simplistic. But the more I’ve read it in Greek the more I’ve come to realize that Mark knew exactly what he was doing when he wrote what he did. In other words, the Markan author was well-educated but chose to write is Gospel for a popular audience.

For more on the historic present, see Wallace, 526-532; Constantine R. Campbell, Basics of Verbal Aspect in Biblical Greek (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2008), 43, 66-68.

[11] White, 263.

[12] France, Mark, 430.

[13] From Lane Dennis, general editor, ESV Study Bible (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2008), 1,999.

[14] Craig Evans, Mark 8:27-16:20, WBC (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 2001), 142. See also Hendricksen, Mark, 432; William L. Lane, The Gospel According to Mark, NICNT (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdman’s Publishing Company, 1974), 395.

[15] Decker, 13.

[16] William L. Lane, The Gospel According to Mark (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1974), 395. Lane mentions three specific passages: Numbers 19:2, Deuteronomy 21:3, and 1 Samuel 6:7.

[17] It should be noted that the description of Judah in Genesis 49:11 isn’t truly prophetic but is, rather, etiological. It is a statement of the immense agricultural wealth of the kingdom of Judah. Normally, one would bind their donkey to a tree but because the grape vines are so abundant one could simply attach it to one of them. This is emphasized further in the same verse: “He washes his garments in wine and his robe in the blood of grapes.” That is, the wine runs like water it is so abundant.

[18] David Garland, Mark, NIV Application Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1996), 427; see also Evans, 142. Evans, in keeping with a more historical understanding of the event, writes that “the explanation may in fact be much simpler [than Jesus’ assuming authority to take the animal]; Jesus evidently made a prior arrangement with a sympathizer.”

[19] This verse represents a third-class conditional sentence wherein a future potential situation is reflected. For more on conditional sentences, see Wallace, 701-712.

[20] Evans, 143.

[21] Darrell Bock, Mark, New Cambridge Bible Commentary (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 288.

[22] France, Mark, 432. Evans notes that “for the Markan community ὁ κύριος may very well have been understood as a reference to Jesus” (Evans, 143). However, while that may be the case, the question is what the textual data warrants. I do not find that simply because ὁ κύριος is used that it must refer to Jesus because of the understanding of the community for which Mark wrote. Are we to assume they were not adept at understanding context?

[23] Bock, 287.

[24] John H. Hayes, “Passover,” in Metzger and Coogan, 572. For more on Hallel Psalms, see W. Derek Suderman, “Psalms,” in Gale A. Yee, Hugh R. Page, Jr., and Matthew J. M. Coomber, editors, Fortress Commentary on the Bible: Old Testament and Apocrypha (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2014), 585-587.

[25] Rikk E. Watts, “Mark,” in G.K. Beale and D.A. Carson, editors, Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2007), 207.

[26] Lane writes that

Jesus did not silence the beggar…because he is at the threshold of Jerusalem where his messianic vocation must be fulfilled. The “messianic secret” is relaxed because it must be made clear to all the people that Jesus goes to Jerusalem as the Messiah, and that he dies as the Messiah. (Lane, Mark, 387)

[27] David E. Garland, Mark, 429. France writes that Jesus’

first dramatic public gesture, therefore, has placed the Galilean preacher firmly in contention for the title ‘King of the Jews’, and that title will be at the centre of his Roman trial. (France, Mark, 435)

[28] Evans writes that the awkwardness of 11:11 “is evidence that the triumphal entry did not conclude in the way its planners, including Jesus, had hoped…The city of Jerusalem did not welcome the prophet – perhaps Messiah – from Galilee as had those among his following.” (Evans, Mark, 146-147.)

[29] Williamson, 201.

[30] Lane, 395.

[31] Donald Hagner, Matthew 1-13, WBC (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 1993), liv.

[32] Grant R. Osborne, Matthew, Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2010), 754, note. 4. The use of a cohortative command such as ἐρεῖτε is common in Matthew’s Gospel but not outside of it. For more, see Wallace, 452-453.

[33] Claus Westermann, Isaiah 40-66, Old Testament Library (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1969), 379.

[34] Craig Keener, The Gospel of Matthew: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2009), 494-495; R.T. France, The Gospel of Matthew, NICNT (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2007), 781.

[35] Donald Hagner, Matthew 14-28, WBC (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 1995), 596. Osborne sees this a bit differently and writes,

It does seem likely that Matthew wants to show a deficient understanding by noting the crowd only considers him a prophet. Yet there is also a christological point, that Jesus is prophet as well as Messiah, as seen in the times Jesus’ prophet office is noted – 13:57 (Jesus calls himself a “prophet without honor”); 16:14 (the people say he is “Jeremiah or one of the prophets”); and 21:46 (the people still consider him a “prophet”; cf. John 6:14; 7:40, 52). Jesus is a prophet and more. (Osborne, 757)

I find this unlikely and agree with Hagner’s assessment that the title is “informational rather than confessional” (596) though I disagree with Hagner’s statement that the crowd making the statement about Jesus is one from Jerusalem. The question was posed by the inhabitants of Jerusalem and answered by those travelling with Jesus on his way to the city. There are therefore two groups in view.

[36] That this is a reference to the prophet like Moses, see France, Matthew, 781-782.

[37] France, Matthew, 772.

[38] France, Matthew, 772, note 13.

[39] For more, see F.F. Bruce, “The Book of Zechariah in the Passion Narrative,” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library (March 1961), 336-353.

[40] For more, see William W. Klein, Craig L. Blomberg, and Robert L. Hubbard, Jr., Introduction to Biblical Interpretation, revised and updated (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 2004), 290; William Sanford Lasor, David Allan Hubbard, and Frederic William Bush, Old Testament Survey, second edition (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1996), 232-233; Andrew E. Hill and John H. Walton, A Survey of the Old Testament, second edition (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2000), 314; Adele Berlin, “Poetry, Biblical Hebrew,” in Metzger and Coogan, 597-599.

[41] “There is little doubt that we are to envision only one animal in Zechariah’s proclamation of the coming king and that the foal of the donkey.” Thomas Edward McComiskey, “Zechariah,” in The Minor Prophets: An Exegetical and Expository Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 1998), 1,167.

[42] David Instone-Brewer, “The Two Asses of Zechariah 9:9 in Matthew 21,” Tyndale Bulletin 54.1 (2003), 90. Instone-Brewer writes,

[The] rabbinic authorities before 70 CE totally rejected the concept of synonymous parallelism in Scripture. They regarded Scripture, including the Writings, as a perflect law. One of the characteristics which they assumed to be part of a perfect law was the lack of redundancy. Any unnecessary repetition involved redundancy, and implied sloppy writing by the divine legislator….They do so because a perfect legislator would have used one line or the other – either a general phrase which would imply the more specific or a specific phrase which would be an example of the general. (92)

[43] Instone-Brewer, 96-97.

[44] Keener, 491.