By and large the New Testament was written in the decades following the death of Jesus of Nazareth in 30 CE. The earliest writings came from a man by the name of Paul, a Pharisee turned Christian who traveled the Mediterranean spreading his message concerning Jesus Christ, the one who “was declared to be Son of God with power according to the spirit of holiness by resurrection from the dead” (Romans 1:3). Paul was a contemporary of Jesus but there is no evidence that the two ever met. If they had, surely Paul would have been the first to let his readers know. Rather, Paul is adamant that the source of his knowledge of the true gospel came via revelation:

For I want you to know, brothers and sisters, that the gospel that was proclaimed by me is not of human origin; for I did not receive it from a human source, nor was I taught it, but I received it through a revelation of Jesus Christ (Galatians 1:11-12, NRSV).

Such rhetoric is part of Paul’s apostolic persona. Whereas others like Peter and James knew Jesus and spent time with him prior to the crucifixion, Paul was not afforded that opportunity. Instead, the resurrected Jesus appeared to him “[l]ast of all, as to one untimely born” (1 Corinthians 15:8; cf. 9:1). But there is no doubt in Paul’s mind that he was chosen by the risen Jesus to preach the gospel: “Christ did not send me to baptize but to proclaim the gospel” (1 Corinthians 1:17a).

Canonical Listings of Pauline Epistles

Everything we know about Paul is derived from two sources: his letters and the Acts of the Apostles. The former are primary sources, that is to say that they are from Paul himself. The latter is secondary, that is to say that it is not from Paul himself. In the canonical New Testament there are thirteen letters that are attributed to Paul: Romans, 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, 1 Thessalonians, 2 Thessalonians, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, Titus, and Philemon. Their order in the New Testament reflects not the order in which they were composed but their category and length. The first nine letters are letters to communities of believers (i.e. Christians in Rome, Christians in Corinth, etc.) while the final four are letters to specific individuals (i.e. Timothy, Titus, and Philemon). Within each category the letters are arranged according to length, from longest to shortest.

|

Pauline Epistles in the Modern New Testament |

|

|

To Communities |

To Individuals |

| Romans (longest) | 1 Timothy (longest) |

| 1 Corinthians | 2 Timothy |

| 2 Corinthians | Titus |

| Galatians | Philemon (shortest) |

| Ephesians *longer than Galatians | |

| Philippians | |

| Colossians | |

| 1 Thessalonians | |

| 2 Thessalonians (shortest) | |

The ordering that we have today was, of course, not the only ordering known from Christian history. In some iterations, Galatians appears first while in others it is 1 Corinthians.

|

The Order of the Pauline Epistles in Canonical Lists1 |

||

|

Marcion

(2nd century) |

Muratorian Fragment (2nd century) |

Papyrus 46 (2nd century) |

| Galatians | 1 Corinthians | Romans |

| 1 Corinthians | 2 Corinthians | Hebrews |

| 2 Corinthians | Ephesians | 1 Corinthians |

| Romans | Philippians | 2 Corinthians |

| 1 Thessalonians | Colossians | Ephesians |

| 2 Thessalonians | Galatians | Galatians |

| Ephesians | 1 Thessalonians | Philippians |

| Colossians | 2 Thessalonians | Colossians |

| Philippians | Romans | 1 Thessalonians |

| Philemon | Philemon | |

| Titus | ||

| 1 Timothy | ||

| 2 Timothy | ||

Noticeably absent from Marcion’s listing are the Pastoral Epistles, i.e. 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus. The same is true of the Pauline codex P46 where seven missing folios at the end likely contained 2 Thessalonians and perhaps Philemon but not the Pastoral Epistles.2 This has led to some speculation that certain communities did not utilize the Pastoral Epistles or consider them canonical. Yet even supposing that to be the case, it is clear that many communities did utilize the Pastoral Epistles and they are included in one of our most significant early witnesses to the New Testament: Codex Sinaiticus (א). The order of the Pauline epistles in א is what we find in our modern New Testaments.3

Pauline Authorship

Canonical lists are useful for telling us what books were frequently in use by Christian communities and were therefore considered sacred to some degree. But this doesn’t tell us anything about the nature of the epistles themselves. What was believed about them is not indicative of the truth about them.

Without exception, each of the so-called Pauline epistles in the New Testament are attributed to the work of the apostle Paul. But we cannot take it for granted that because Paul’s name is attached to those letters that he must have written them. After all, the practice of pseudepigraphy was not uncommon even among Jewish and Christian authors. For example, the book of Daniel was almost certainly not written by a sixth century Jewish exile by that name and likely originated in the second century BCE.4 The same is true of works like the Epistle of Barnabas, a second century CE letter purportedly written by Paul’s missionary companion Barnabas. The Pauline epistles are no exception to this and scholars have divided the thirteen letters into two general categories: undisputed epistles and disputed epistles. The disputed epistles can be further divided into the Deutero-Pauline epistles and Pastoral Epistles.

|

The Pauline Epistles |

||

|

Undisputed Epistles |

Deutero-Pauline Epistles |

Pastoral Epistles |

| Romans | Ephesians | 1 Timothy |

| 1 Corinthians | Colossians | 2 Timothy |

| 2 Corinthians | 2 Thessalonians | Titus |

| Galatians | ||

| Philippians | ||

| 1 Thessalonians | ||

| Philemon | ||

The undisputed epistles are generally regarded as authentic by New Testament scholars. Paul almost certainly wrote them. There is less certainty about the Deutero-Pauline Epistles since internal evidence suggests they were likely written after the death of Paul.5 The Pastoral Epistles were almost certainly not composed by Paul.6

But if the Pastoral Epistles were not written by Paul, then who wrote them and when?

The Origin of the Pastoral Epistles

That the Pastoral Epistles depended on some kind of Pauline corpus seems certain. The author(s) of the Pastoral Epistles seems to have some level of acquaintance with the epistles of Romans, 1 Corinthians, and Galatians.7 The author(s) wanted to sound like Paul but internal evidence makes it relatively clear that they weren’t Paul.8

- Roughly thirty percent of the vocabulary in the Pastoral Epistles does not appear anywhere else in Paul’s undisputed letters.9 For example, the only place in the entire Pauline corpus where we find the word eusebeia (i.e. “godliness”) is in the Pastoral Epistles.10

- Vocabulary that is featured in the undisputed letters is either omitted or appears with less frequency or with a different theological meaning in the Pastoral Epistles. For example, nowhere in the Pastoral Epistles do we find any usage of euangelizō (“to proclaim the gospel”), a verb Paul uses nineteen times in the undisputed letters.

- In the undisputed letters, Paul seems to look favorably upon women in ministerial roles (Romans 16:1, 3, 6, 7) and affirms that in Christ “there is no longer male and female” (Galatians 3:28). However, in the Pastoral Epistles the structure of the church is almost exclusively male and women are instructed to “learn in silence” and are not permitted to teach men (1 Timothy 2:11).

But if not Paul, then who? The answer to that question may forever be out of our reach as we have virtually no clue as to who the author could have been. Undoubtedly, the author was part of a community that was favorable toward Paul and his ministry or else they would not have tried to imitate him in their writings. Beyond that we cannot be certain.

Determining when the Pastoral Epistles were written fairs a little better. When we read Paul’s undisputed letters we see virtually nothing about how churches were to be structured. It seems that those communities were far more egalitarian and that there was no set authority structure. But this is not the situation we find in the Pastoral Epistles. In fact, it is assumed that authority structures exist and “Paul” writes to address the qualifications for those who are seated in positions of power. What does this tell us? It tells us that while the undisputed letters derive from an early era of Christianity, the Pastoral Epistles are probably from a time closer to the second century.11 And since Paul died sometime in the 60s CE, he could not possibly have been their author.

Enter Pop-Apologetics

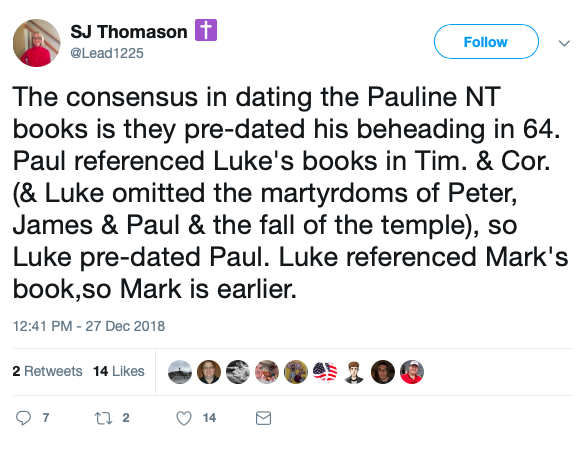

Such views are not in line with many of the standard takes in evangelical circles. This is especially true among pop-apologists for whom early dating is essential to their views on inerrancy and inspiration. For example, I was recently alerted to a tweet put out by pop-apologist SJ Thomason concerning Paul and the dating of the Gospels. She wrote,

The consensus in dating the Pauline NT books is they pre-dated his beheading in 64. Paul referenced Luke’s books in Tim. & Cor. (& Luke omitted the martyrdoms of Peter, James & Paul & the fall of the temple), so Luke pre-dated Paul. Luke referenced Mark’s book, so Mark is earlier.12

It should go without saying that people who have been beheaded cannot compose literature of any kind and so the “consensus” is simply common sense. But there is a hidden assumption in what Thomason has written, namely that all of the canonical Pauline epistles were written by Paul. As I briefly discussed above, this is not the consensus view and of the two Pauline epistles Thomason mentions only 1 Corinthians is deemed authentic by virtually all New Testament scholars.

So to what is Thomason referring when she claims that “Paul referenced Luke’s books in Tim. & Cor.”? Paul refers to the Lord’s Supper in 1 Corinthians 11:23-26, a passage that shares many similarities with the Lukan version of the event (Luke 22:14-23). It is possible that Paul was using Luke’s Gospel as his source for his words but he asserts that he received the instructions “from the Lord” (1 Corinthians 11:23) and not from a written source. Furthermore, it appears that Paul had already handed these instructions down to the Corinthians and was simply reiterating them in his epistle. It is more likely that the Lukan text was influenced by Paul rather than vice versa.

But what about her reference to Timothy? Well, in 1 Timothy 5:18 we read of two sayings. The first is from the Torah: “You shall not muzzle an ox while it is treading out the grain” (cf. Deuteronomy 25:4). The second is found nowhere else but the Gospel of Luke: “The laborer deserves his to be paid” (cf. Luke 10:7). This tells us that whoever wrote 1 Timothy had the Gospel of Luke in his mind. And since Thomason’s assumption is that 1 Timothy was written by Paul then it must be the case that Luke’s Gospel was written before Paul wrote 1 Timothy. And since Luke’s Gospel was dependent upon Mark’s Gospel then Mark’s Gospel was written before that. And since Thomason believes in Matthean priority,13 then Matthew’s Gospel would have come before Mark’s Gospel. Therefore, these writings are all attested to be very early.

However, there are a couple of things to bear in mind. First, the saying of Deuteronomy 25:4 that we find in 1 Timothy 5:18 is not the only place where Paul cites that specific saying. In 1 Corinthians 9:9 we find it as well: “For it is written in the law of Moses, ‘You shall not muzzle an ox while it is treading out the grain.’ Is it for oxen that God is concerned?” In context, Paul is explaining that he and his fellow laborers like Barnabas have the right to expect compensation for their work for the gospel. Paul wrote,

Who at any time pays the expenses for doing military service? Who plants a vineyard and does not eat any of its fruit? Or who tends a flock and does not get any of its milk?

Do I say this on human authority? Does not the law of Moses say the same. For it is written in the law of Moses, You shall not muzzle an ox while it is treading out the grain.’ Is it for oxen that God is concerned? Or does he not speak entirely for our sake? It was indeed written for our sake, for whoever plows should plow in hope and whoever threshes should thresh in hope of a share in the crop. If we have sown spiritual good among you, is it too much if we reap your material benefits? If others share this rightful claim on you, do not we still more? (1 Corinthians 9:7-12a)

Of course, Paul refuses such compensation on the grounds that he does not want to “put an obstacle in the way of the gospel of Christ” (1 Corinthians 9:12b). Regardless, it is odd that Paul, having employed the passage of Deuteronomy both here and in 1 Timothy 5:18, fails to employ the words of Jesus from the Gospel of Luke. The rhetorical effect of adding the Lukan Jesus’ saying here in the context of 1 Corinthians would have served to emphasize all the more Paul’s desire to keep obstacles out of the way of the gospel. For if even Jesus himself stated that those who labor deserve to be paid then Paul would be demonstrating how much he cares for his integrity of his gospel ministry that he would be willing to not enjoy such compensation.

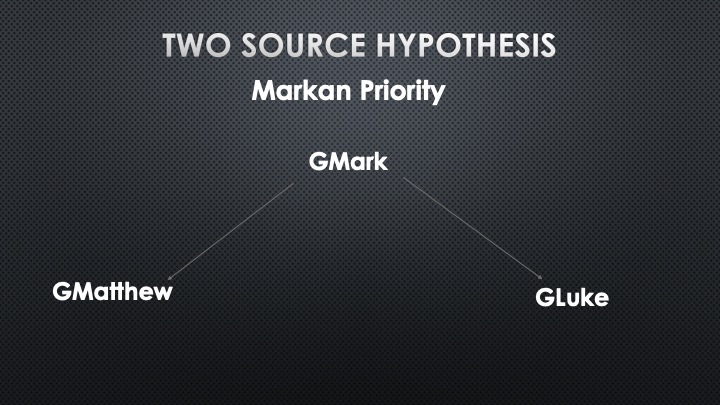

Second, Thomason speaks of the “consensus” view of the dating of the Pauline epistles but flatly ignores the consensus view concerning the origin of the Gospels themselves. Far-and-away the consensus position is that of Markan priority: Mark composed his Gospel first and both Matthew and Luke relied on Mark’s Gospel when composing their own.

And the consensus view of New Testament scholars concerning when the Gospel of Mark was written is sometime during the Jewish War (66-73 CE), likely after the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE. This means that both the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles were written after 70 CE, perhaps in the 80s or as late the early second century.14

But what about the lack of any mention of the death of Peter or Paul or of the destruction of the Temple? Aren’t these indicative of a date before 70 CE? In reality, this is a red herring as we would not expect an author, writing about a specific period, to write explicitly about events not in his purview. Thomason has indicated in another tweet that she accepts a date of 90 CE for the writing of the Gospel of John yet it never mentions Peter’s or Paul’s death or the destruction of the temple in explicit terms.15 If the lack of such elements is a sign of pre-70 authorship, then surely the Gospel of John was written before 70 CE. Yet few New Testament scholars – evangelical or otherwise – accept such reasoning. Apparently, neither does Thomason.

Conclusion

It seems Thomason’s attempt at dating the Gospels early based upon Pauline literature fails. The epistle of 1 Timothy was likely composed after Paul had already been killed and thus cannot be used as evidence that Paul knew of the Gospel of Luke. Nor is the reference to the Lord’s Supper in 1 Corinthians 11 evidence of dependence upon Luke as it is more likely that the Lukan text knew of the Pauline rather than vice versa. The consensus view among New Testament scholars is that of Markan priority and the consensus view of the date of the Markan Gospel is that it was likely composed sometime just before or just after the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE.

Acknowledgment: Twitter user @towerofbabull first alerted me to Thomason’s tweet and requested I write an article in response. That they would ask me to do so is very humbling and I appreciate the confidence that they place in my work.

NOTES

1 Adapted from Arthur G. Patzia, The Making of the New Testament: Origin, Collection, Text & Canon, second edition (IVP Academic, 2011), 251.

2 Bruce M. Metzger, Manuscripts of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Greek Palaeography (OUP, 1981), 64.

3 With the exception of the epistle to the Hebrews which in א appears after Romans and before 1 Corinthians. This was due to an early belief that Hebrews was written by the apostle Paul, despite its anonymous nature. In modern New Testaments it appears at the end of the Pauline collection as the first of the Catholic Epistles.

4 See Amateur Exegete, “Evangelical Eisegesis: A Dalliance with Daniel, part 1” (12.2.18), amateurexegete.com.

5 See Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings, sixth edition (OUP, 2016), 438-448.

6 See Ehrman, 449-452.

7 Gerd Theissen, The New Testament: A Literary History (Fortress Press, 2012), 96-97.

8 Calvin J. Roetzel, The Letters of Paul: Conversations in Context, fifth edition (WJK, 2009), 159-162.

9 Roetzel, 160.

10 See Amateur Exegete, “The Mystery τῆς εὐσεβείας” (4.8.18), amateurexegete.com.

11 Ehrman writes, “The clerical structure of [the Pastoral Epistles] appears far removed from what we find in the letters of Paul, but it is closely aligned with what we find in proto-orthodox authors [i.e. Ignatius, Irenaeus, etc.] of the second century.” Ehrman, 456.

12

14 SJ Thomason, “Was Mark or Matthew the First to Write the Gospel?” (3.3.18), christian-apologist.com. Accessed 28 December 2018.

15 See Marcus J. Borg, Evolution of the Word: The New Testament in the Order the Books Were Written (HarperOne, 2012), 424-426.

16

It should be noted that it is not the case that “[m]ost Bible experts agree apostle John” wrote the Gospel that bears his name. Scholars aren’t sure who wrote it but it seems very unlikely that it was a disciple of Jesus.

Featured image: Wikimedia Commons.

Use of a “Lord’s Supper” is a very dubious argument, quite a few variant cult’s/mysteries had those

LikeLiked by 1 person

The way she seems to see it it is dubious indeed. The Lukan text was influenced by the Pauline rather than the other way around.

LikeLike

This argument is probably inspired in part by similar arguments from J. Warner Wallace, which means that the alleged reference is to Luke 10:7 from both 1 Timothy 5:18 (verbatim) and 1 Corinthians 9:14 (conceptually). I think that 1 Corinthians reflects Paul’s knowledge of the Jesus sect’s lifestyle commitment to proclaiming the coming kingdom, and 1 Timothy reflects pseudo-Paul’s familiarity with 1 Cor. and Luke.

On a related note, I’m inclined to think that 2 Timothy is entirely or partially authentically Pauline, but that 1 Timothy is almost certainly pseudoepigraphic.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thomason has a love for JWW so you’re probably right.

As for 1 Cor 9:14, I think I’m with you on that. Surely if Paul had the Gospel of Luke on hand he would have quoted it often, especially on matters like divorce and remarriage, the poor, etc. That he doesn’t tells me he did not have it available to him.

LikeLike

It seems to me that compared to other aspects of scripture the order and dating are relatively inconsequential. Of much more practical value would be looking at why the claims are still taken seriously given what we know about how things work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think that for pop-apologists like SJ and others dating the Gospels as early as possible means that they are more historically accurate, i.e. there was less time for legendary material to develop. This is, of course, a non sequitur. But their arguments for early dating just do not hold up to scrutiny. So they end up being wrong on both fronts.

Dating does tells us how ideas developed, especially with regards to the Synoptic Problem.

LikeLiked by 1 person