Recently I was asked by Dr. Kipp Davis if I would be willing to post a piece he has written in response to Egyptologist David Falk (Ph.D. University of Liverpool, 2015) concerning his understanding and reading of Deuteronomy 32:8-9. For those of you who may be unfamiliar with him, Dr Kipp Davis (Ph.D. University of Manchester, 2009) is a Hebrew Bible scholar and a specialist in Second Temple Judaism and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Dr. Davis has held positions at Trinity Western University, Museum of the Bible, and the University of Agder in Norway, and his work on Jewish manuscript forgeries in private collections has been featured on CNN, ABC News, PBS NOVA. He has a YouTube channel in which he regularly features counter-apologetics videos, teaching videos and videos unpacking the many fascinating and important contributions of the Dead Sea Scrolls to biblical scholarship.

In the article that follows, Davis demonstrates what I find to be the hallmarks of good scholarship: measured language, knowledge of and appreciation for other scholars in the field, and a desire for truth. I heartily commend this post to you, readers, as it was my distinct privilege to be asked to do this on Dr. Davis’s behalf. While the comment section to this post will be open, those who wish to contact Dr. Davis more directly may do so through his Academia.edu page.

“STAY IN YOUR LANE”

WHY DAVID A. FALK SHOULD REFRAIN FROM IMPERSONATING A BIBLICAL SCHOLAR ON YOUTUBE

Kipp Davis

I recently took the time with two other scholars, Dr. Joshua Bowen from Digital Hammurabi, and Dr. Dan McClellan, a “Scripture translation supervisor” from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to review a sampling of questions from a Q&A stream that was broadcasted on the Ancient Egypt and the Bible YouTube channel on 17 December.1 We discussed the poor handling on this video of questions concerning slavery in the Old Testament, and the problematic, polytheistic reading of an interesting passage in Deut 32:8–9. The passage in the received text, from which most of our English translations are derived, reads:

When the Most High gave the nations their inheritance,

When He separated the sons of man,

He set the boundaries of the peoples

According to the number of the sons of Israel.

“For the LORD’s portion is His people;

Jacob is the allotment of His inheritance (NASB).

However, the preservation of an alternative reading in the Septuagint, which has also received ancient support from the oldest copies of Deuteronomy found in the Dead Sea Scrolls, has convinced scholars that in actual fact, this reading is the result of an editorial emendation to eliminate what was once a clear attestation of an early Israelite polytheistic worldview. The original passage reads:

When the Most High apportioned the nations,

when he divided humankind,

he fixed the boundaries of the peoples

according to the number of the gods;

the LORD’s own portion was his people,

Jacob his allotted share (NRSV).

The reason Drs Bowen, McClellan and I set out to do the short review was because the presenter in the stream, Dr. David A. Falk, provided a response that not only ignored the crucial textual evidence for the passage, but demonstrated that he had little or no idea about the ongoing scholarly discussion behind its history of transmission. This is poor scholarship, especially when it is dressed up in the guise of authority, as Falk is known to do. David Falk is an Egyptologist who earned his Ph.D. from the University of Liverpool, and he now makes Christian apologetics videos on YouTube aimed at addressing the relationship between Egyptian texts and history and the Bible, and he also provides answers to critical questions and problematic issues in the biblical texts. If you have not watched our response, you should do so, as Drs Bowen, McClellan and myself carefully and clearly unpack precisely the serious shortcomings in Falk’s style of apologetics.

A viewer of our video response, it seems, felt it necessary to comment on Falk’s original stream, and Falk took the time to elaborate on his handling of the passage in greater detail.

This brings us to my essay, here. In what follows, I shall go over Falk’s more detailed remarks to—once again—demonstrate how far out of his depth this Egyptologist is when it comes to the Bible. My response systematically follows what Falk has written in four parts: first, 1) we shall consider the disclaimer he added to his video, which essentially reveals that Falk is disingenuously disseminating information about topics he really knows little or nothing about. I will then follow this with my rebuttal to his three-fold handling of the passage in question in Deut 32:8–9 from the perspectives of 2) its poetical “genre,” 3) the crucial text critical discussion, and 4) the meaning of the text.

1

Say We Shouldn’t Believe You

Without Saying We Shouldn’t Believe You

In his written remarks included in the comments to the original video, Falk begins by providing a disclaimer to his work on YouTube:

As a reminder, it is important to realize that when I answer questions on my live streams that I do them as a live show, generally without notes or prior preparation. I also don’t normally get the questions in advance, so I don’t even know which questions I am going to receive and nobody screens the questions. So I don’t necessarily promise that any question will flesh our every last detail or reference all the literature on the subject, nor do I necessary hold to that the answers are even necessarily correct. I do make mistakes at times and even sometimes change my opinions when I receive new data that points to the contrary. My answers are intended to address the direct inquiry and are not a substitute for a sound Biblical commentary.

I think it is absolutely crystal-clear from the stream itself that Falk simply did not know at the time that he addressed the question of Mark S. Smith’s reading of Deut 32:8–9 the pivotal textual issues behind this passage. Furthermore, Falk also ignores the reasons for Prof. Smith’s discussion, which have come to form the consensus opinion within biblical scholarship. Here is the question as it was first posed to Falk by viewer, “Swift Sea”: “I’ve heard Mark S. Smith say that Deuteronomy 32:8-9 is evidence that Old Testament religion was polytheistic, because it says that the god El gave Israel to Yahweh. What are your thoughts on this argument?”

Falk proceeds to look up the passage, and then cautions that “there is a lot of reference in Deuteronomy 32 to other forms of literature,” but without any further explanation about what he is getting at, and why. He then he reads it, and after some time to collect his thoughts concludes that Smith is probably wrong in his reading because of the poetical nature of the text:

I’ve got some big … big, big, big, big doubts here that Mark Smith is correct … because … we do actually have here a sort of another couplet—almost a chiasm. So, we have on the outside of this sort of chiasm … “when the Most High gave the nations there their inheritance,” and then it’s followed by, “when he separated the sons of man.” Okay, and then the next couplet … begins with, “he set the boundaries of his people according to the number of the sons of Israel.”

Falk goes on to say that:

It’s not so much that Elyon is giving it all out, and, “Oh, here, Yahweh—have your share too!” That’s not what the text is saying; that’s a really poor reading of the text! It’s more along the lines of, “Okay here is the division of the nations, okay, but I am reserving one portion for myself!” The Lord is dividing the peoples, but he is also saying there is one people that is special; one people that is set apart for his own purposes.

From his on-the-fly reading, Falk posits that Prof. Smith’s argument stems from a source critical view of the text—that the two different titles used of deities might indicate different sources behind the surviving text: “I really think here that Mark Smith is taking, say, a source critical approach to the text, and basically saying, ‘Oh, you got Elyon; you’ve got Yahweh. It’s two gods!’ Obviously, no, he’s wrong here. That’s just a bad reading of the of the text.”

In my response with Dr. McClellan—which Falk has called “a desperate straw man and quote mining”2—we both maintained that the primary issue with what Falk was doing was his apparent, total ignorance of the textual issues behind this passage, and as Dan pointed out, his lack of awareness regarding what Smith has been arguing for over twenty years now. My problem is much less with Falk’s reading—which is admittedly, minimally plausible (but, we will get to that)—than it is with the fact that he is promoting himself as an authority, and providing an off-the-cuff response to a question he clearly does not adequately grasp. It is obvious. Just by watching the clip itself there is no doubt that Falk is searching for answers as he is reading the text, and his response confirms that impression with aplomb. Would it really have been too difficult for Falk to simply admit that he is unaware of the text critical discussions surrounding this text, and their implications? Alternatively, if he is indeed properly versed in the scholarship of the text, why does he tacitly ignore it when furnishing an answer; proceeding so far as to accuse Prof. Smith of providing “just a bad reading of the text”?

I have done my fair share of live streams, and I have entertained plenty of questions that I just don’t know enough about to offer a satisfactory answer. The proper response in these instances is to be honest about our limitations—even as specialists, and to move on. What is so extremely problematic about Falk’s approach—as outlined above—is that he will speak with equal confidence about matters in which he is actually an expert as he does when he is “riffing” on a biblical text that he has seen seemingly for the first time. By providing a disclaimer after the fact to inform his audience that “the answers are [not] even necessarily correct,” but without any indication of which answers those may be at the outset, is blatantly dishonest. How does a viewer ascertain when Falk is disseminating accurate information about the dating of Egyptian cities like Pi-Rameses and Pi-Thom, or about the rule of Rameses III, and when he is pontificating blindly about a textual discussion than he clearly has not followed like in Prof. Smith’s work on Deut 32:8– 9? When Falk pretends that all these things are addressed in equal measure he is misleading his audience insofar as his own qualifications to answer half of the questions he fields.

2

“Genre,” Poetics and Pointless Parallels

In any event, and—after the fact—Falk has now provided a more carefully thought-out response to the question that was originally posed. Here we get a chance to see what was rattling around in his head at the time of his Q&A video, that Dr. McClellan and I were somehow expected to guess about without his say so (but I digress):

“Okay, there are three text considerations wrapped up in these questions: (1) the nature of the genre, (2) the lower text critical issues, and (3) the meaning of the passage itself. So, let’s look at each of these.” I think it is worthwhile at the outset to note that this distinction Falk is drawing between “higher” and “lower criticism” in his second question is fairly antiquated. These are not terms that you commonly see anymore within biblical scholarship; scholars prefer now to discuss the individual critical models outside of this old classification: “lower criticism” is simply textual criticism, and the “higher criticisms” comprised of source, tradition, redaction, rhetorical criticisms, along with any number of the social and literary theories which have developed over the past century. What is often the case today is that when the older terms are used, it is by Evangelicals and others who are dubious about the results of the so-called “higher criticism.” In the words of the preeminent text critical scholar of our day, Emanuel Tov, “Emphasis on the antithesis between the higher and lower criticism is, however, misleading, for textual criticism is not the only discipline on which higher criticism is based. Linguistic, historical, and geographical analysis, as well as the exegesis of the text, also provide material for higher criticism.”3 Given what I have seen from Falk in his brief treatments of models like the Documentary Hypothesis, or social and religious theories of the settlement period in the early Iron Age Levant, I cannot help but think this is merely a reflexion of his own faith commitment, which has significantly biased him against critical biblical scholarship. This is just another “tell” which reveals that Falk’s content is much more apologetic than it is scholarly.

But, how does Falk, then, handle these three questions he has posed for examining the text of Deut 32:8–9? The first of these unfolds as follows:

(1) The nature of the passage is that it is poetry. While I cannot give an exhaustive understanding of the ANE poetic genre in a comment reply, I would recommend The Art of Biblical Poetry by Robert Alter for a better understanding of how Biblical poetry works. However, when we broach Biblical poetry, we need to do so understanding that it is organized as a doublet, with each singlet being a single unit of thought where the meaning is somehow transformed by its association with the other singlet. For the passage at hand, verse 8 is a doublet composed of two singlets which is obvious if one bothers to actually crack open a Hebrew text. And we will see why that is important when we get to consideration 3.

To be clear, the “genre” of the passage in question does not really have anything to do with the question at hand, which is whether or not the poem reflects a polytheistic worldview in which YHWH was a member of a larger council of deities. In any event, what Falk is getting at is that the parallelism through which Hebrew poetry is constructed comprises parallel statements in two stanzas, with the second elaborating the first. In this instance (and ignoring the much more consequential textual issues for the moment) the first of the two clauses in the Masoretic Text reads i) “When ʿElyon apportioned the nations as an inheritance”; ii) “when he separated the sons of Adam.” The second follows, i) “he erected boundaries of the people”; ii) “according to the number of the sons of Israel.” If we are evaluating the poetical quality of this text, then the question of how—or even whether—the second stanza informs the first in the second clause will become important. What is ʿElyon doing, here? Is he setting the number of nations according to the “seventy sons of Israel,” as known from Gen 46:27 and Exod 1:5? On this point, the text is not explicitly clear, but as we shall come to see, the emendation of this particular passage in some forms of Deuteronomy is a late reflexion of ideas affecting the entire Pentateuch. But in any event, I do not consider the “genre” of the passage to be a meaningful question insofar as the history of the text is concerned. There is not much information to be gleaned from this question to improve our understanding of the transmission history in Deut 32:8–9.

3

“Lower” [Bar] Text Critical Ramblings

Falk continues in his contemplation of the much more significant text critical issues:

(2) There is a lower text consideration at the end of verse 8, “sons of the gods” vs “sons of Israel.” So let’s survey the various lower text sources:

MT: bny ysrʿl, “sons of Israel.”

LXX: aggelon theou, “angels of God.” Note, that the LXX uses the singular form of “God.”

SP: bny ysrʿl, “sons of Israel.”

4QDeut: bny ʿlohym, “sons of the gods.”

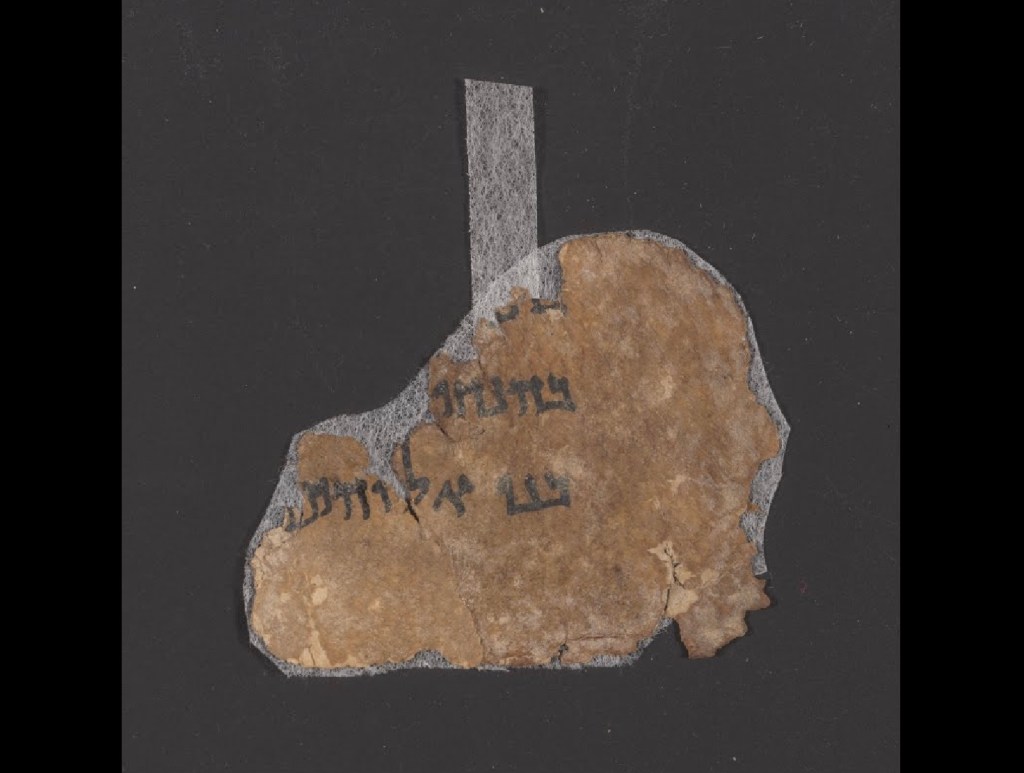

Falk has gotten the sources right for the most part, but it is sloppy of him to designate the Qumran MS. as merely “4QDeut.” There are at least 30 copies of scrolls containing text from Deuteronomy, and they are not heterogenous. The MS. in question is actually 4QDeutj (4Q37). There are 46 identifiable fragments surviving from this scroll which contains various texts from Deuteronomy 5–11, Exodus 12–13, and Deuteronomy 32—in that order. The MS. dates to 50 C.E., and it is the oldest surviving copy of this portion of the “Song of Moses” in Deut 32:8–9 by a wide margin. The excerpted nature of this particular MS. (that is, one not containing the entire book of Deuteronomy) will become significant in how we evaluate the original shape of the text later on.

But there is another, important point to make here regarding the ancient sources of the so-called “Song of Moses,” which appears in Deuteronomy 32. There are a handful of other excerpted MSS from Qumran which also contain only the Song, occasionally along with a selection of other biblical passages. Another of these MSS, 4QDeutq (4Q44) dates to the mid-to-late first century B.C.E., and it also preserves text from Deut 32:43, which clearly reflects an ancient, polytheistic worldview. By comparing this text to the other textual witnesses mentioned below, it becomes abundantly clear that the earliest version of the Song appears in this MS., and that the polytheistic elements have been cleverly removed through careful editing in later editions. This is why we included in our discussion of Falk’s work on Deut 32:8–9 this MS., and it is, once again, sloppy and negligent of him to ignore it in his more thorough written response to our objections. The poor scholarship continues.

So, what are these “lower text sources” cited by Falk? Text critical scholars of the Hebrew Bible are generally agreed that during the mid-to-late Second Temple period (c. 250 B.C.E.–70 C.E.) there were at least three “versions” of the biblical texts that we know of. These survived in later medieval manuscripts. On this point, Falk is correct: “The current consensus among lower text critical scholars is that the MT, LXX, and SP all came from different text type families, and the DSS contains examples from all the text type families.”

The “Masoretic Text” (MT) is the standardised form of the text that was transmitted by a medieval Jewish scribal group known as the Masoretes. It is the text that was inherited by the “rabbinical Jews” after the destruction of Herod’s Temple in Jerusalem. Prior to the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the oldest witnesses to this version were in the Leningrad Codex (c. 1000 C.E.) and the Aleppo Codex (c. 925 C.E.). The Masoretes were responsible for inventing the vowel-pointing system some time after the sixth century C.E.; this system for vocalisation continues to be transmitted with the text to this day.

The “Septuagint” (LXX) is the form of the text that was used by the translators of the Hebrew Bible into Greek, which occurred in the third century B.C.E. Numerous papyrus fragments of the Greek text have survived from the third and fourth centuries C.E., most notably in the Chester Beatty collection. A complete version of the LXX appears in the Codex Sinaiticus from the fourth century C.E., and is still considered one of the most important of all the biblical manuscripts.

The “Samaritan Pentateuch” (SP) is a version of the text that was preserved by the Samaritan “Israelite” community in Palestine. Scholars tend to trace the roots of the Samaritans as far back as Alexander the Great in the late fourth or early third century B.C.E., but the earliest extant manuscript copies of the Samaritan Pentateuch date to 1100 or 1200 C.E.4 The text itself is generally characterised by harmonisations of problematic Torah texts, corrections of errors that survive in the MT and LXX, and theological alterations which promote the priority of the Samaritan community and their sanctuary at Mount Gerazim.5 Notably, the SP shows substantial agreement with the LXX over the MT, and scholars tend to posit that the source-texts behind these versions were probably very similar.

On the basis of this brief survey, Falk draws the following conclusion:

From the evidence that we have, the word “sons” appears in all text families and is the original reading. The difference between “Israel” and “God/gods” seems split down the middle. The idea that the “post-2nd temple jews didn’t like the scriptures” is probably incorrect given the antiquity of the SP, which rivals the source texts of the LXX itself and the fact that Samaritans considered themselves Israelites but not Jews. It would be very strange for 2nd temple Jews to change the text for the MT, and the Samaritans to make the exact same change for the SP.

Falk takes for granted, here, that the change of the Hebrew text in Deut 32:8 between בני אלהים (= ἀγγέλων θεοῦ/υἱοὶ θεοῦ, “sons of God,” 4QDeutj LXX) and בני ישראל (“sons of Israel,” MT SP) is something that occurred in the Second Temple period. But to be clear, there is virtually no manuscript support for the MT and SP readings from before the ninth century C.E. In the field of textual criticism considerable weight is set on the earliest readings; especially when there is such a vast distance of time between the manuscript witnesses. In this case, ALL of the earliest manuscript evidence supports the former reading.

However, this does not prevent Falk from making the rather astonishing assertion: “there does appear to be a bifurcation of the text, one branch of which is preserved in the sources for the LXX/4QDeut (sic.) and another for MT/SP.” This is, on the face of it, a simple explanation for the evidence derived from the editions, but it utterly fails in the in view of the complex nature of the “biblical” texts as they appeared in the Second Temple period. While text critics will often speak without nuance of the three great witnesses to the biblical text in MT, LXX and SP, this is conventional short-hand for a bewilderingly more complicated picture. In the words of Tov:

As an alternative to the generally accepted theory of a tripartite division of the textual witnesses, it [has been] suggested … that the three above-mentioned textual witnesses constitute only three of a larger number of texts. This suggestion thus follows an assumption of a multiplicity of texts, rather than of a tripartite division. The texts are not necessarily unrelated to each other, since one can recognize among them several groups. Nevertheless, they are primarily a collection of individual texts whose nature is that of all early texts and which relate to each other in an intricate web of agreements and differences. In each text one also notices unique readings, that is, readings found only in one source. As will be clarified below, all early texts, and not only those that have been preserved, were once connected to one another in a similar web of relations.6

And another of the great text critical voices of our time, Eugene Ulrich, has posited:

The fundamental principle guiding this proposal is that the Scriptures, from shadowy beginnings until the final, perhaps abrupt, freezing point of the Masoretic tradition, arose and evolved through a process of organic development. The major lines of that development are characterized by the intentional, creative work of authors or tradents who produced new, revised editions of the traditional form of a book or passage.7

The point here being, that any attempts to draw clean lines between “branches” of the texts from the period in question are completely anachronistic. In fact, insofar as the present passage is concerned, Tov has actually assigned 4QDeutj (which agrees with LXX in Deut 32:8) to a different textual grouping, or “family,” altogether on the basis of its frequent disagreement elsewhere with LXX: “Many texts are not exclusively close to any one of the texts mentioned above and are therefore considered non-aligned. They agree, sometimes significantly, with MT against the other texts, or they agree with SP and/or LXX against the other texts, but the non-aligned texts also disagree with the other texts to the same extent.”8 In other words, the variation between the versions is not a simple “bifurcation” that reflects different textual traditions in this case. Rather, the situation is substantially more complicated, and will require a greater investment of attention beyond an amateurish sizing up the individual readings.

But for Falk, he unwittingly suggests that there are only two possibilities:

The first possibility is that “sons of the gods” was changed to “sons of Israel” in accordance to political and religious dynamics of the Late 2nd Temple period. This reading is favored by secular scholars who believe that the Pentateuch was being finalized after the Babylonian exile because for them it shows redaction because the “sons of the gods” reading reflects the milieu of 2nd Temple literature. However, this seems a bit strange precisely because the “sons of god” theology is itself a 2nd Temple period codification of earlier ANE myth. Why switch from one perfectly good 2nd Temple reading to another? Moreover, there is a chronology issue in that synchronizing the redactions becomes problematic when one considers that the change “sons of Israel” is believed to be post-LXX, and yet the SP most likely predates that change. It seems that this possibility is an ad hoc explanation that serves to confirm a cognitive bias.

The first of these is a reflexion of precisely the problem mentioned above, and is undoubtedly a product of Falk’s extremely poor, unsophisticated understanding of the development of the biblical text. What he is drawing up as a prevailing theory of the textual history in this passage could not be further from the truth. In actual fact, scholars are generally agreed that BOTH the older reading preserved in LXX and 4QDeutj and the “obviously … antipolytheistic revision”9 in MT and SP were already in circulation during the Second Temple period. However, the field is virtually uninmous in promoting the priority of the 4QDeutj reading as the original text even while maintaining that the MT/SP revision co-existed alongside of it in the Second Temple period.

An explanation for this is neatly dispensed in a recent article by Benjamin Zeimer. Zeimer points out that this MS., 4QDeutj—along with 4QDeutq, which also preserves an ancient, polytheistic reading in Deut 32:43—is an excerpted text, and not a complete copy of the Book of Deuteronomy. As a result of the harmonising tendencies observed in the transmission of biblical texts (including the Samaritan Pentateuch) during the mid-Second Temple period, the reading in Deut 32:8 was changed from “sons of God” to “sons of Israel.” This occurred in part as a calcification of monotheism, but also in an effort to promote continuity with other parts of Deuteronomy and with the rest of the Torah. Zeimer writes:

The Pentateuch is structured by a more or less coherent system of numbers and personal and geographic names. A “number of the sons of God” (Deut 32:8 OG [Old Greek ] and 4QDeutj) does not at all fit in this system. In contrast, the “number of the sons of Israel,” is well established within the Pentateuch. Seventy names are specified in Gen 46:8ff. under the rubric “These are the names of the sons of Israel,” and the number “seventy” is mentioned explicitly in Gen 46:27 (MT+SP), repeated in Ex 1:5 (MT+SP) and again in Deut 10:22 (MT+SP+LXX). This number equals the names of the people specified in the table of nations in Gen 10 (MT+SP+LXX). So the equation of “the borders of the nations” with the “number of the sons of Israel” (בְּהַנְחֵ֤ל עֶלְיֹון֙ גֹּויִ֔ם בְּהַפְרִידֹ֖ו בְּנֵ֣י אָדָ֑ם יַצֵּב֙ גְּבֻלֹ֣ת עַמִּ֔ים לְמִסְפַּ֖ר בְּנֵ֥י יִשְׂרָאֵֽל Deut 32:8 MT+SP) is well founded in the Pentateuchal composition, but was less impressive for the Greek translator of Deuteronomy, and had no relevance at all for the independent transmission of the poem.10

So, the reason the more ancient reading survives in an excerpted text like in 4QDeutj is because on it’s own there is no need to bring the Song of Moses into consistent alignment with the rest of Deuteronomy or the Pentateuch. The same holds for the polytheistic readings in 4QDeutq, which bolsters the argument for the priority of these readings. The Song is an independent composition. Scholars have long recognised the antiquity of this text on its own, which pre-dates the current form of the book of Deuteronomy. Excerpted MSS like 4QDeutj and 4QDeutq help to illustrate this fact, as well as provide powerful testimony to the development of the book of Deuteronomy and the rest of the biblical texts. To summarise:

- the original form of Deut 32:8 read “when Elyon gave nations as an inheritance; when he divided the sons of Adam; he set the boundaries of the people according to the number of the sons of God.” This archaic reading can be set at any point in the Assyrian, Babylonian or Archaeminide period. It survives in the excerpted MS. 4QDeutj and the LXX, and attests to the earliest known form of the “Song of Moses” now in Deuteronomy 32.

- a revision of this text occured to reflect a monotheistic ideology that became more intensified in the Hellenistic period, but also to align the text more closely to the rest of Deuteronomy and the Pentateuch. The text of the second stanza was changed at some point in the Second Temple period to read “he set the boundaries of the people according to the number of the sons of Israel” in accordance with other texts like in Gen 46:8, 27; Exod 1:5 and Deut 10:22. This reading survives in both the MT and SP versions, which attest to the earliest form of the complete version of the book of Deuteronomy as we have it, with the appended Song of Moses.

Again, Falk presents himself as not only blissfully unaware of the complexities of the textual issues of the passage, he is also content to invent his own rationale for why “secular scholars” maintain the priority of 4QDeutj and the LXX in this instance, which amounts to conjectural nonsense. But then, he goes on to furnish us with his preferred reading:

The second possibility is that “sons of Israel” is a Late Bronze/Early Iron Age reading and that the “sons of the gods” reading is a branch text of the original Urtext, the change of which occurred in the 2nd Temple Period. So this second possibility then suggests that an original source was changed to make it consistent with the mythological readings of the 2nd Temple Period. This explanation is consistent with the text-type branches that are observed in the source texts.

It needs to be stressed that this is not a view that is espoused by any serious textual scholar, and once again, it bears pointing out that Falk’s presentation of the manuscript evidence is unsophisticated, naïve and misleading. I assume the “mythological readings of the Second Temple period” to which he refers to be found in apocalyptic writings like Daniel, 1 Enoch and Jubilees. But again, this is not a view of the textual history of this passage that has been promoted by any scholars, and for which there is no evidence. By far the most widely accepted explanation for the variants and the textual history of the passage is along the lines of that which I have outlined above. But to beat a dead horse, I should like to cite Ulrich’s reading of the text: “The MT intentionally replaces the polytheistic term, just as it did the more mythic and polytheistic readings in 4QDeutq at Deut 32:43.”11 Moreover, according to Tov, who is still the pre-eminent Hebrew Bible textual critic of our age:

In its probably original wording, reconstructed from 4QDeutj and LXX, the Song of Moses referred to an assembly of the gods (cf. Psalm 82; 1 Kgs 22:19), in which “the Most High, ʿElyon, fixed the boundaries of peoples according to the number of the sons of the God El.” The next verse stresses that the LORD, יהוה, kept Israel for himself. Within the supposedly original context, ʿElyon and El need not be taken as epithets of the God of Israel, but as names of gods also known from the Canaanite and Ugaritic pantheon. It appears, however, that the scribe of an early text, now reflected in MT SP, the Targumim, the Peshitta and the Vulgate, did not feel at ease with this possibly polytheistic picture and replaced “sons of El” with בני ישראל, ”the sons of Israel,” thus giving the text a different direction by the change of one word.12

The academic discussion of just this passage, which reflects the synopses provided by Tov, Ulrich and Zeimer, is extensive.13 Falk is just patently wrong, here, but instead of acknowledging his limitations in handling this text, he has doubled-down by retreating to the outdated “principles” of textual criticism which were popular in the first-half of the twentieth century:

So with a dead tie down the middle, which is the more likely reading? In lower text criticism, there is a main principle called “lectio difficilior potior” (Latin for “the more difficult reading is the stronger”). This principle states that all other considerations being equal that the more unusual reading is more likely the original. So when you state that the MT/SP reading is “gibberish,” then that is not grounds to reject that reading but to accept it and figure out what the reading means.

The so-called “principles” of textual criticism—including this one—have been largely rejected by modern text critical scholars, as explained by Tov: “in many instances this rule has been applied so subjectively, that it can hardly be called a textual rule or canon. For what appears as a linguistically or contextually difficult reading to one scholar may not necessarily be difficult to another.”14 But, even granting Falk the usage of his out-dated approach to this text, it must be stressed that all other considerations are NOT equal. The manuscript evidence is overwhelmingly in favour of prioritising the reading of the passage preserved in the LXX and attested in 4QDeutj. This Qumran MS. is far-and-away the oldest witness to this reading, and its survival outside the Book of Deuteronomy and in a stand-alone copy of the Song of Moses reinforces its antiquity, as demonstrated above. The alternative readings in SP and MT—while probably much earlier than attested—do not receive any manuscript support prior to the tenth century C.E. So, no. Even if we grant the principles for the sake of salvaging the late redaction in MT and SP, they are inapplicable because the manuscript evidence is so definitive on its own.

4

What Does It All Mean,

and Does It Even Matter?

Falk concludes his review of the passage with his third text consideration: what is the meaning of the passage itself?

So we are now left with then how to read Deut 32:8. My translation of the text is “When Elyon made the nations to inherit as he divided the sons of man; he set the borders of the nations for the sons of Israel.”

This brings us back to the genre considerations. This verse is actually a couplet divided into two singlets as follows:1: “When Elyon made the nations to inherit as he divided the sons of man;”15

2: “He set the borders of the nations for the sons of Israel.”

So we have two thoughts here, not just one. In the first singlet, the writer sets out that Elyon is causing the nations to inherit as he divides them. This thought is the leading singlet and is not strictly dependent upon the second singlet. Thus, whether the MT/SP or LXX/4QDeut (sic.) readings prevail is almost irrelevant to the meaning of the first singlet.

On this last sentence I completely agree, but this does nothing at all to salvage Falk’s case, since the passage—literarily speaking—can and does work both ways, with both readings. All this manages to demonstrate is that whoever edited the passage in whatever direction, they had the linguistic and artistic sensibilities to craft it such that the poetical structure would not be disrupted. Falk concludes:

When we parse the reading of the passage according to its genre consideration, then the meaning of the second singlet is clear. The L-preposition is a dative, but not a dativus modi (“according to”), but a dativus commodi sive incommodi (“for benefit or harm of”). The second singlet is clearly saying that God divided the nations not forgetting to include the Israelites in that decision.16 For although God divided the peoples giving each nation their land, he included the Israel in his divine foreknowledge. This reading works perfectly with the rest of the chapter and is coherent with the rest of the concerns expressed in the Pentateuch, which includes Israel coming into its land inheritance, i.e., the Promised Land.

So, Falk’s reading here provides a decent explanation for the meaning of the edited passage (so long as we ignore the problems in his translation), but again, it adds no insight at all into the developmental history of the text itself. (Besides, we might point out here that by his own out-dated employment of the principle of lectio difficilior potior this particular reading could be disqualified as the original for being “less unusual.” This is, of course, an example of precisely why scholars have abandoned these arbitrary and subjective so-called principles.)

Concluding Thoughts

So, to summarise:

1) Falk’s first consideration of the passage in Deut 32:8–9 in terms of its poetical “genre” is inconsequential to the original form and the textual history.

2) Falk’s discussion of the sources and textual witnesses behind the passage is unsophisticated and naïve. Moreover, it fails to carefully consider how the passage itself as it appears in the oldest witness—the excerpted MS. 4QDeutj—actually strongly attests to the developmental history of not only the theology of its Second Temple Jewish handlers, but also the early shape and redaction history of the book of Deuteronomy and the Pentateuch.

3) Falk’s consideration of the “meaning” of the passage is unhelpful in assessing its textual history, since, in the first place, both forms of the text are clearly meaningful, and, in the second place, his somewhat tortured reading only explains the text in its final form.

David Falk is an Egyptologist who probably knows actual things about Egyptology. But when it comes to the Bible, he is clearly, demonstrably well out of his depth. In this sampling of his handling of a single question from his live streams I have shown that Falk is unaware of scholarly discussions of this particular text in Deut 32:8–9. But even worse than this, he relishes in that ignorance, and uses this unearned air of confidence to beguile his audience with a false impression of his authority on matters he knows little about. And this is a problem, because most of the questions that Falk fields come from nervous Evangelicals who are concerned about the problematic history of the Hebrew Bible. They depend upon his bravado to bolster their own insecurities about difficult topics like the Documentary Hypothesis, slavery, polytheism and the origins of Deuteronomy and the propagandistic Deuteronomistic history. They are emboldened by his hand-waving and casual disregard of the voluminous and intimidating consensus of scholarship on these matters. Falk’s astonishingly dismissive demeanour when addressing serious questions like these should disqualify his opinion at the outset, but even upon unpacking his position as I have done so above, we come to discover that despite all his bluster, Falk is a poor resource for reading and understanding the biblical text.

In short, stay in your lane, Dr. Falk, and leave the biblical scholarship to actual biblical scholars.

Endnotes

1 Our review can be viewed here. The original video can be viewed here.

2 This is an utterly fallacious charge that Falk has repeated in his most recent stream from 31 December, in response to a questioner who inquired about the content of our critique of his work.

3 Emanuel Tov, Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible, 2nd Rev’d Edn. (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2001), 17. Tov published an extensively revised and expanded third edition of his seminal work in 2011.

4 Add 1846 possibly dates to the beginning of the twelfth century, although mention has been made of a single page from a codex containing text from Genesis which could date as early as 800 C.E.

5 Emanuel Tov identifies eleven characteristic features of the SP text, which distinguish it rather singularly from both the LXX and the MT: three forms of “harmonising alterations”: 1) “changes on the basis of parallel texts, remote or close”; 2) “addition of a ‘source’ for a quotation”; 3) “commands and their fulfilment.” Three types of “linguistic corrections”: 4) “orthographical peculiarities”; 5) “unusual forms”; 6) “grammatical adaptations.” Added to these are 7) “content differences,” and two types of “linguistic differences”: 8) “morphology” and 9) “vocabulary.” A second layer of features which distinguish the “Samaritan” elements of the text include 9) “ideological changes”; 10) “phonological changes”; and 11) more “orthography.” Tov, Textual Criticism, 85–97.

6 Tov, Textual Criticism, 160.

7 Eugene Ulrich, “Multiple Literary Editions: Reflections toward a Theory of the History of the Biblical Text,” in Current Research and Technological Developments on the Dead Sea Scrolls: Conference on the Texts from the Judaean Desert, Jerusalem, 30 April 1995, ed. D.W. Parry and S.D. Ricks, STDJ 20 (Leiden: Brill, 1996), 89.

8 Tov, Textual Criticism, 116, cp. also 115.

9 Benjamin Zeimer, “A Stemma for Deuteronomy,” in The Samaritan Pentateuch and the Dead Sea Scrolls, ed. Michael Langlois, Contributions to Biblical Exegesis and Theology 94 (Leuven: Peeters, 2019), 182.

10 Zeimer, “A Stemma for Deuteronomy,” 184.

11 Eugene Ulrich, The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Developmental Composition of the Bible (orig. pub. 2015; Leiden: Brill, 2017), 162.

12 Tov, Textual Criticism, 269.

13 Julie Ann Duncan, “37. 4QDeutj” in Qumran Cave 4.IX: Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Kings, ed. Eugene C. Ulrich et al., DJD 14 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1995), 75–91; idem., “Considerations of 4QDtj in Light of the ‘All Souls Deuteronomy’ and Cave 4 Phylactery Texts’, The Madrid Congress: Proceedings of the International Congress on the Dead Sea Scrolls, Madrid 18–21 March, 1991, ed. Julio Trebolle Barrera and Luis Vegas Montaner, STDJ 11 (2 vols.; Leiden: Brill, 1993) 2: 199-215 and Pis 2-7; Ulrich Dahmen, “Das Deuteronomium in Qumran als umgeschriebene Bibel,” in Das Deuteronomium, ed. Georg Braulik, OBS 23 (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2003), 269–309; idem., “Neu identifizierte Fragmente in den Deuteronomium-Handscriften vom Toten Meer,” RevQ 20/4 (2002): 571–81; Moshe Weinfeld, “Grace After Meals in Qumran,” JBL 111 (1992): 427–40; J.T. Millk, Qumrȃn Grotte 4.II: II. TefilIIin, Mezuzot et Targums (4Q128–4Q157), DJD 6 (Oxford; Clarendon, 1977) 34-79; Josef Ziegler, “Zur Septuaginta- Vorlage im Deuteronomium,” ZAW 72 (1960): 240–46; Patrick W. Skehan, “Qumran and the Present State of Old Testament Text Studies, The Masoretic Text,” JBL 78 (1959): 21–25; idem., “The Qumran Manuscripts and Textual Criticism,” in Volume du Congrès, Strasbourg, 1956, VTSup 4 (Leiden: Brill, 1957), 148–60; idem., “A Fragment of the ‘Song of Moses’ (Deut. 32) from Qumran,” BASOR 136 (1954) 12–15.

14 Tov, Textual Criticism, 304.

15 This is really quite an awkward translation without the object, which is something that one finds typically in Hifil conjugations of the verb נחל, “to impart as an inheritance.” In Falk’s translation we are left wondering what it is that the nations are receiving as their hereditary property, and why. Usually, this is land, and this would be more clearly implied by the more conventional translations like the NRSV and ESV which treat גּוִֹים, “the nations,” as the object. Moreover, Falk’s decision, then to render the parallel infinitive בְּהַפְרִידֹ֖ו, “when he divided,” in the accompanying clause as a comparative expression is equally problematic. This form of the verb with the preposition בּ would most naturally indicate that this is rather a temporal clause, just like the temporal clause which opens the prior, connected stanza.

16 But this does not follow from the translation that Falk has cobbled together above. I think it is a good indication if his explanation of the text requires elaboration beyond what the actual translation will allow, then his interpretation is probably well off the mark to begin with.

“We are not amused, Dr. Falk” – Asherah.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Talmidimblogging and commented:

Love this!!

LikeLike

“ So, the reason the more ancient reading survives in an excerpted text like in 4QDeutj is because on it’s own there is no need to bring the Song of Moses into consistent alignment with the rest of Deuteronomy or the Pentateuch. The same holds for the polytheistic readings in 4QDeutq, which bolsters the argument for the priority of these readings. The Song is an independent composition. Scholars have long recognised the antiquity of this text on its own, which pre-dates the current form of the book of Deuteronomy. Excerpted MSS like 4QDeutj and 4QDeutq help to illustrate this fact, as well as provide powerful testimony to the development of the book of Deuteronomy and the rest of the biblical texts.”

I think this argument would be more airtight if there were manuscripts of the song existing on its own, rather than excerpts of the whole book. Even though the song existed on its own, all the evidence seems to show is that some excerpted versions of the book, focusing on the song, have the variant reading “sons of the gods”. The manuscript tradition by itself doesn’t establish that the independently-existing poem originally had that reading.

For the record, I think it’s better to assume that “sons of the gods” is the older reading (unlike Falk), but the manuscript evidence doesn’t seem to back that view one way or another.

LikeLike

Correction: “ if there were *a more stable, definite manuscript tradition* of the song existing on its own”

LikeLike

Thank you for your feedback.

For the record, 4QDeut-q is just such a ms. you have hoped for, preserving ONLY Deut 32 on its own, with no identifiable affiliation with the rest of the book of Deuteronomy. But to reiterate, the manuscript tradition on its own is so convincing precisely because it leads to a natural and perfectly plausible explanation for both 1) why some of these excerpted mss continued to survive well into the late Second Temple period, and also 2) why the changes were made to the text in copies of the book of Deuteronomy. Alternative explanations for why the text may have been altered in the other direction continue too be unconvincing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“ For the record, 4QDeut-q is just such a ms. you have hoped for, preserving ONLY Deut 32 on its own, with no identifiable affiliation with the rest of the book of Deuteronomy.”

But again, you don’t know that. That too could just be an excerpt of the entire book, given what else is available. That’s what I was trying to say with my correction.

“ it leads to a natural and perfectly plausible explanation … continue too be unconvincing”

This is, again, a highly-subjective judgment that is ultimately rooted in how one thinks Israelite religion evolved.

LikeLike

But unless I am misunderstanding you, how would we even know an excerpt in this instance from a manuscript of the Song existing on its own? Even when it comes to the copies of biblical texts that we do have the is evidence of only a very small handful of these that were titled.

Yes, the findings are subjective, but the explanation dos not stem from a view of Israelite religion, so much as it does from careful observations and considerations of the texts along with evidentiary-based ideas about how early Jews collected and transmitted their scriptures.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“ how would we even know an excerpt in this instance from a manuscript of the Song existing on its own?”

On p. 185 of “A Stemma”, Ziemer notes, “so-called 4QDeutj contained the Decalogue, some other passages from Exodus and Deuteronomy, and the Song of Moses. So-called 4QDeutq contained, apparently, only the Song of Moses.” Of course, he then goes on to say that 4QDeutq represents an independent witness of the song.

But my point is that because fragments like 4QDeutj and 4QDeutk1 are excerpted collections that presume the background of a set of books, it seems natural to think that 4QDeutq is just an excerpt of one of those books as well (ditto 4QPhylN), even if it only features the one poem. Therefore, it seems to me that to assert that 4QDeutq is a witness to an independent tradition is not an “evidentiary-based idea” that comes “naturally” from the manuscript evidence, but rather one that relies on other assumptions about what counts as more “theologically archaic”. I hope that’s clearer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

But even if we ignore the theological question for the moment, would you not agree that the 1) observed harmonizing tendencies in textual traditions like the SP combined with 2) the fact that the alternate reading in MT SP aligns with the harmonizing tendencies (in this case, bringing the division of the nations into correspondence with other Pentateuchal and Deuteronomy texts which make mention of the “seventy nations”) indicate that the direction of the change is toward what appears in MT SP?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Honestly, I don’t buy the harmonization argument either. In fact, I think the “sons of the gods” reading confirms to the preceding books of the Torah better than the “sons of Israel” reading. Before the flood and thus before the dividing of the nations, the sons of god have sex with human women, giving rise to the Nephilim, so it makes sense from a narrative perspective that El Elyon would divide the nations according to their number because divine council politics — Yahweh-El shows the other gods who’s boss. By contrast, the sons of Israel don’t enter the picture until long after the dividing of the nations, so from a narrative perspective, they can’t be relevant to it. (Unless of course, there was an older tradition involving a prophecy about the sons of Israel and the number of the nations, but that doesn’t seem plausible to me.)

If “sons of Israel” was meant to harmonize the narrative, it only created more problems.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I should also point out that this part of Moses’s speech in Deut 29:24-26 dovetails very well with the “sons of the gods” reading: “[…] indeed all the nations will wonder, ‘Why has the Lord done thus to this land? What caused this great display of anger?’ They will conclude, ‘It is because they abandoned the covenant of the Lord, the God of their ancestors, which he made with them when he brought them out of the land of Egypt. They turned and served other gods, worshiping them, gods whom they had not known *and whom he had not allotted to them*…’”

According to this part, building up to the song, other nations have their allotted gods, lesser deities, but Israel has Yahweh, who did the allotting in the first place. The “sons of the gods” reading is most definitely in harmony with this, more than “sons of Israel”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

An excellent post! Absolutely great.

I’ve been arguing this with apologists for a while, though I myself am quite an amateur. I gave up. Michael Heiser is another one of those academics who will twist evidence to try and preserve a monotheistic reading of the text of Deut. 32:8-9, and his arguments are all really bad (such as arguing that cognates of “Elyon” are not used for El at Ugarit, which is a nonsequitur because we only have two such cases of it used as an appellative ever anyways, for Baal, so the sample size is too small to be meaningful; he ignores an Ammonite ostracon which has the name ‘eli’el or “El is highest”; he ignores the Sefire I treaty which has a waw explicativum ‘l-w-‘lyn or “El who is most high”; ignores that “elyon” is used as a title of El in various other Biblical passages [he does actually admit to Gen. 14:18-22, which was also a case where the name “Yahweh” was inserted into the text in v.22 according to Tov]). He also has this weird anachronistic argument comparing Deut. 32:8-9 to Deut. 4 and arguing that Deut. 32:8-9 must be similar otherwise they are contradictory… and like… yes, Deut. 4 (a later text) is contradictory as Mark S. Smith notes.

By far my favorite (terrible) argument of Heiser’s is when he argues that Deut. 32:7 uses El epithets for YHWH citing phrases ימות עולם and שנות דור־ודור. And like… no… not a single one of these is an epithet applied to YHWH in verse 7. He just completely either misread or deliberately misrepresented the passage. At least, from my understanding.

Falk also neglects relevant Canaanite data that we have as well. For instance, we know that the god El is responsible for dividing the nations according to the number of his children. Philo of Byblos wrote:

Also, when Kronos [Elus] was traveling around the world, he gave the kingdom of Attica to his own daughter Athena. […] In addition, Kronos gave the city Byblos to the goddess Baaltis who is also Dione, and the city Beirut to Poseidon and to the Kabeiri, the Hunters and the Fishers, who made the relics of Pontos an object of worship in Beirut. [using the Attridge and Oden translation] [1]

Likewise, there is also the Baal Cycle which has this curious little passage (translated by Mark S. Smith):

Then you shall head out

For Divine Mot, [Smith notes this as a possible omission by a scribe]

At his town, the Pit,

Low, the throne where he sits,

Filth, the land of his heritage [or inheritance].

Note that the word “heritage” here is a cognate term to the Hebrew. The Ugaritic term is nḥlth which is cognate of the Hebrew term used in Deut. 32:8-9, נחלתו. Simon Parker also translates part of the Aqhat epic as having the following passage:

Dine and wine the gods,

Uphold and honor them,

The lords of Memphis, allotted by El

Danatiya the Lady attends

Anyways, just some notes from my end. I wrote up this absurd 22000 word survey of evidence, scholarly debates, and references on the issue in the course of my debate. So if you are at all interested, feel free to hit me with an email (theliteratebookworm@gmail.com) and I’ll send it your way. Again, all the work of an amateur, just an amateur with a fixation problem on this lol.

Michael Heiser, “Are Yahweh and El Distinct Deities in Deut. 32:8-9 and Psalm 82,” Hiphil 3 (2006), 9 pages.

Simon B. Parker, Ugaritic Narrative Poetry (SBL Press, 1997) [for translations from Smith and Parker]

Harold Attridge and Robert Oden Jr., Philo of Byblos, The Phoenician History: Introduction, Critical Text, Translation, Notes, Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 9 (Washington, D.C: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1981) [for Byblos quote]

C. L. Seow, Myth, Drama, and the Politics of David’s Dance (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1989), p. 52n [waw explicativum note; position also upheld by Mark Smith, R. de Vaux, Zdravko Stefanovic, and C. L’Heureux if I remember correctly)

Again, an excellent post Dr. Davis. Glad to see such a brilliant take down of Falk’s pseudoscholarship.

[1] As a note, I know “Elioun” is attested in Philo of Byblos and not applied to El. Given that “Elioun” is described as dying via being killed by a wild beast, my guess is that this is Byblian Adonis, who was worshiped in the area and seemed a patron deity, as Lucian’s De Dea Syria attests. This would just attest that “elyon” as a title was widespread in usage, as it is applied to Baal twice in a single Ugaritic text, to Yahweh in the Hebrew Bible, to El in various places (also Bible), and perhaps a few other deities as well.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Instead of having to email dozens of people over and over again, why don’t you upload your essay to dropbox and provide a link to it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much for this! I was unaware of the Canaanite texts pertaining to the topic.

I continue to find it very weird that in Heiser’s interpretation of the passage YHWH’s portion is described as נחלה. If Heiser’s reading is correct, then why the hell is YHWH leaving himself an inheritance of the property that he already owns? How does that make a lick of sense?

LikeLiked by 2 people

I know right! His arguments are all kinds of absurd in my experience, and they become weird and convoluted. I have yet to ever see anyone make a good case for a monotheistic reading of this passage, and it gets even more complicated to try and do so once you factor in the other data. If I recall, also, the Targum Jonathan adds in “seventy” before “bene” which would be really funny because that aligns with the “seventy sons of Athirat” in Ugaritic texts (mentioned in the Baal Cycle if I recall correctly).

It is quite an entertaining debate nonetheless. One of my favorite things to study.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really do think there’s more to this, though. Even Second Temple Judaism wasn’t entirely monotheistic: There’s a consistent mythos in the Bible as finished (even taking Deut. 32 out of the picture for the sake of argument) that Yahweh created the world with gods (see Job, a late text) and set the gods over the nations (see Deut 29:26), only to judge them for their misdeeds against the vulnerable (Psalm 82) and take things over himself. This is a view where Yahweh seems to occupy the role of El Elyōn in the Ugaritic texts, so there doesn’t seem to be a total discomfort towards polytheism in the Second Temple Period.

Complicating this are the parallels drawn between the mighty men who run the world and the gods the nations worshipped. Psalm 82 explicitly says that “like any man you [gods] will fall.” Moreover, the children and grandchildren of Israel/Jacob (in the P text) corresponds to the number of the sons of Athirat: seventy. In all, I think there’s more than just a desire to repress polytheism at play here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

RESPONSE TO ANONY

Psalm 82 has YHWH as a part of a council, not the head of the council. In fact, by comparison to other divine council scenes, Min Suc Kee notes that YHWH is likely not the highest in the council in Psa. 82, i.e. it does not belong to him. He is standing as the accuser within its midst. David Frankel goes as far as to argue that YHWH here functions in the ha-satan role in the council of El. So Psa. 82 does not actually help your case at all. Basically every scholar since Simon B. Parker’s influential essay in the 90s also takes Psa. 82 as an El council scene. Deut. 29:25-26 is also a later text and is one that Smith notes is likely in response to Deut. 32:8-9 or the idea at least. Again, it mirrors Deut. 4. You are attempting to interpret Deut. 32 in light of *later* texts responding to it. That would be like me trying to interpret the work on gender performance and identity by Judith Butler through polemical treatises written by anti-SJW’s. I wouldn’t come out of this with a sensical reading of the original work. Only the skewed one from the anti-SJW’s. Similarly, reading Deut. 32:8-9 in light of texts responding to it and pushing a clear agenda, is not going to give me a clear vision of it either. Same with Job.

Internally, it makes no sense to identify Elyon and YHWH as the same figure here, because YHWH receives an inheritance (נחלה) in v.9. The (נחלה) are given to the sons of god by Elyon specifically in v.8 and even uses the same terminology, using נָחַל which comes from (no surprises) נחלה. If any deity receives נחלה they must therefore be among the bene elohim. Otherwise, it actually ruins the poetic parallelism of the passage… which would be hilarious given Falk makes such a big deal about the poetic structure and genre of the text.

People don’t receive inheritances from themselves…

“This is a view where Yahweh seems to occupy the role of El Elyōn in the Ugaritic texts, so there doesn’t seem to be a total discomfort towards polytheism in the Second Temple Period.”

You don’t alter a text to eliminate “sons of [the] gods” unless you are uncomfortable with the implications thereof. The fact that they altered it to “sons of Israel” means they were uncomfortable with the fact that the passage indicated that YHWH was among the “sons of [the] gods”, i.e. that he was one of El Elyon’s sons.

David Frankel, “El as the Speaking Voice in Psalm 82:6-8,” Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 10 (2010), online journal

Min Suc Kee, “The Heavenly Council and its Type-Scene,” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 31.3 (2007), 259-273

Simon B. Parker, “The Beginning of the Reign of God – Psalm 82 as Myth and Liturgy,” Revue Biblique 102.4 (1995), pp. 532-559

Solomon Nigosian, “Linguistic Patterns of Deuteronomy 32,” Biblica 78.2 (1997), pp. 206-224

Paul Sanders, The Provenance of Deuteronomy 32 (Leiden: Brill, 1996)

D. A. Robertson, Linguistic Evidence in Dating Early Hebrew Poetry (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 1972)

Matthew Thiessen, “The Form and Function of the Song of Moses (Deuteronomy 32:1-43),” Journal of Biblical Literature 123.3 (2004), pp. 401-424

LikeLiked by 1 person

I realize I’m taking up a lot of space, but it’s just that something doesn’t rub me the right way about the logic here. I appreciate all of your patience and listening.

“Psalm 82 has YHWH as a part of a council, not the head of the council. In fact, by comparison to other divine council scenes, Min Suc Kee notes that YHWH is likely not the highest in the council in Psa. 82, i.e. it does not belong to him. He is standing as the accuser within its midst. David Frankel goes as far as to argue that YHWH here functions in the ha-satan role in the council of El. So Psa. 82 does not actually help your case at all.”

But he’s judging ALL the gods in a way that stresses Yahweh’s superiority and indeed, if this WERE as old a text as you say, why would Yahweh be occupying the ha-Satan role? He’s a storm god. I think what’s more likely going on here is that the psalm is a deliberate polemic against worshipping lower deities than the Most High Yahweh. It invokes divine council scenes where the focus is on some god standing IN the midst of the other gods just to reject that very focus. It uses the language and setup of those scenes at the beginning to deliberately subvert them.

“Basically every scholar since Simon B. Parker’s influential essay in the 90s also takes Psa. 82 as an El council scene. Deut. 29:25-26 is also a later text and is one that Smith notes is likely in response to Deut. 32:8-9 or the idea at least. Again, it mirrors Deut. 4.”

Again, my point is that later texts like Deut 29 demonstrate that Second Temple Jews weren’t uncomfortable with polytheism, as long as Yahweh was on top.

“You are attempting to interpret Deut. 32 in light of *later* texts responding to it. That would be like me trying to interpret the work on gender performance and identity by Judith Butler through polemical treatises written by anti-SJW’s. I wouldn’t come out of this with a sensical reading of the original work. Only the skewed one from the anti-SJW’s. Similarly, reading Deut. 32:8-9 in light of texts responding to it and pushing a clear agenda, is not going to give me a clear vision of it either. Same with Job.”

The exilic text Job also illustrates my point that Jews weren’t as embarrassed about polytheism as you say. Why else are the sons of God in the divine council scene?

“Internally, it makes no sense to identify Elyon and YHWH as the same figure here, because YHWH receives an inheritance (נחלה) in v.9. The (נחלה) are given to the sons of god by Elyon specifically in v.8 and even uses the same terminology, using נָחַל which comes from (no surprises) נחלה. If any deity receives נחלה they must therefore be among the bene elohim. Otherwise, it actually ruins the poetic parallelism of the passage… which would be hilarious given Falk makes such a big deal about the poetic structure and genre of the text.”

Logically, the god of Israel (“El contends”) would be El, right? So why is Yahweh receiving it? Indeed, how did Yahweh manage to go further than other storm deities, becoming identified with El himself?

“People don’t receive inheritances from themselves…”

If a king is parceling treasure out, there’s nothing incoherent with him keeping a big part of it for himself. No?

“You don’t alter a text to eliminate “sons of [the] gods” unless you are uncomfortable with the implications thereof. The fact that they altered it to “sons of Israel” means they were uncomfortable with the fact that the passage indicated that YHWH was among the “sons of [the] gods”, i.e. that he was one of El Elyon’s sons.”

But I’m questioning whether it was altered from “sons of Israel” to “sons of Elim”. “Sons of Israel” doesn’t harmonize the text at all and “sons of Elim” seems to fit in with Second Temple theology. At least, that’s how I could see it happening.

LikeLike

1) Judgment does not require him to be the highest deity in the pantheon. L’Heureux pointed out that there is an Ugaritic text which has El and Baal both functioning as judges together.

’l yṯb b‘ṯtrt El sat enthroned with Astarte

’l ṯpṭ bhd r‘y El judged with Haddu, his shepherd

Haddu = Baal Hadad.

So nope, your logic still doesn’t follow. That YHWH is judge does not make him the highest deity. He would still function like ha-satan in the accusing scene in Zech. 3. There is no evidence that it is functioning to subvert that theme. I’d add that Frankel argues even further that the god El is the speaking voice.

2) “Again, my point is that later texts like Deut 29 demonstrate that Second Temple Jews weren’t uncomfortable with polytheism, as long as Yahweh was on top.”

Hence my point… they are reacting against a text which doesn’t have YHWH on top. You don’t have to respond or alter a text which already has YHWH on top. You don’t need to make responses to things which agree with you.

3) “The exilic text Job also illustrates my point that Jews weren’t as embarrassed about polytheism as you say. Why else are the sons of God in the divine council scene?”

It is irrelevant to the discussion. I don’t care if they had no issue with polytheism (I largely agree that they didn’t). The issue is that they don’t like El Elyon on top. Which Deut. 32 has. Job is not relevant to that issue.

4) “Logically, the god of Israel (“El contends”) would be El, right? So why is Yahweh receiving it? Indeed, how did Yahweh manage to go further than other storm deities, becoming identified with El himself?”

What are you on about? El is lord of the gods. Israel is one of the lands apportioned in Deut. 32:8 that is then split up and given to one of the bene elohim. And Yahweh didn’t go “further” than others. Other deities got merged with El characteristics also, actually. Syncretism was a pretty common trait of the ANE, just look at the Hellenistic-Canaanite syncretisms in Palmyra, or Philo of Byblos. Yahweh is not sui generis.

5) “If a king is parceling treasure out, there’s nothing incoherent with him keeping a big part of it for himself. No?”

It is not an inheritance if he just keeps something aside for himself. It is not an “allotted inheritance” if he is just setting it aside for himself. I’m not sure you know how these words work.

6) “But I’m questioning whether it was altered from “sons of Israel” to “sons of Elim”. “Sons of Israel” doesn’t harmonize the text at all and “sons of Elim” seems to fit in with Second Temple theology. At least, that’s how I could see it happening.”

“sons of Israel” actually does harmonize the text. It isn’t “Israel” that they are harmonizing but the emphasis of the passage. By inserting “sons of Israel” they therefore eliminate the possibility of YHWH being a son of Elyon. Therefore, the two must be identified, because YHWH cannot be a son of Israel. This, as a result, makes it consistent with their later theological views with YHWH on top. I’d add that “sons of Elim” would make the text even WORSE for them, because “Elim” could contain an enclitic mem and therefore be read as “sons of El” (this is the EXACT trait found in Ugaritic texts I might add, which would just make it explicit that El and YHWH are different deities in this passage). Your reading seems incoherent.

Your questioning of the text is incoherent and clearly you are not that familiar with the relevant scholarship, at least not in my opinion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

But notice that Ugaritic text has BOTH Baal and El acting together. I’d think you’d have to read into Psalm 82 to think that it’s El speaking while Yahweh is merely standing there. And clearly, Yahweh is the one being exalted in the passage.

What am I on about? The fact that Israel’s god would seem to be “El”, given the name. If Yahweh is the god of Israel, it seems you could say Yahweh=El. And I’m not talking about syncretism across cultures. I’m talking about one culture, Canaanite culture, where Yahweh was considered a junior deity before being identified with El. And if Yahweh were an outside deity being brought in, why wasn’t he just identified with El right off the bat? Why go through the process of being a junior deity first, FOLLOWED BY being equated with El?

Re: “inheritance”… It’s poetry. Does the expression “inheritance” have to be taken that literally so as to preclude an entity keeping something for himself? Other nations have their inheritance, but Israel is special because Yahweh-El kept it for himself. Is metaphor not a thing all of a sudden?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Read Frankel’s paper before making more comments. The passage says that God passes judgment in their midst. So that means if El is the speaking voice, and YHWH is judging, then they are acting… together. You just haven’t really read the passage very thoroughly.

You are mixing generics and names. Israel is “god contends” and does not necessarily need to indicate El. You are forgetting that El functions as both proper name and generic term both in Canaanite and in Israelite texts. I would further add that… “israel” is an interpolation and you’ve yet to give a singularly coherent reason to think otherwise except this weird series of convoluted arguments.

“it’s poetry”

And it is taken literally in verse 8 and has a parallel in verse 9. It must be literal otherwise verse 8 makes no sense, and therefore verse 9 must be literal, otherwise the poetic parallelism is broken. The fact that you said it is poetry is why.

And it is not a metaphor if it is just a word being used to indicate a completely different concept. At that point it is just a person not knowing how words work. Metaphors are phrases or figures of speech meant to apply to things they don’t literally apply to. “Their bones are hard as bricks” is a metaphor with “brick” functioning to describe the hardness. “inheritance” does not describe a king… not doing anything. If he is distributing land that he already owns, and keeps this bit… he has done nothing to it. Therefore “inheritance” cannot be a metaphor. Israel isn’t receiving anything. If your reading is correct and YHWH the highest god, Israel receives no inheritance. It is just reserved. “Inheritance” is not a metaphor for “reserve”. That doesn’t even logically make sense. If “inheritance” is a metaphor it must be describing God’s reservation of land… in which case it is completely nonsensical as a metaphor. “That reservation of land is as inheritance” is inherently contradictory in conception. Metaphors illuminate things, not make them incoherent. The concept of the metaphorical thing is to help elucidate or hammer home something. I.e. “hard as brick” works because bricks are hard. Inheritances are not “reserved and priorly owned property whose hands never changed” nor even a similar in concept. Thus, to say it is a metaphor for Yahweh reserving property, is to make it conceptually and grammatically nonsensical in every way.

If you want to argue metaphors, you’d better not do it with me… a person who has spent years in poetry classes in university lol. Go to Falk’s channel if this is what you want to do.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Read Frankel’s paper before making more comments. The passage says that God passes judgment in their midst. So that means if El is the speaking voice, and YHWH is judging, then they are acting… together. You just haven’t really read the passage very thoroughly.”

Verse 1: “God presides in the great assembly; he renders judgment among the gods” (NRSV)

Hebrew:

אֱלֹהִים, נִצָּב בַּעֲדַת-אֵל; בְּקֶרֶב אֱלֹהִים יִשְׁפֹּט.

*Elohim* is in the *congregation of El*, aka the divine assembly. The straightforward interpretation is that “Elohim” and “El” refer to one entity. Not two. I would think the writers wouldn’t have made it this ambiguous if Yahweh and El were distinct. And having looked at Frankel’s paper, I just have more questions: Where in the Ugaritic texts is there any scenario along the lines of El condemning ALL the other gods to death and pretty much granting a junior deity permission to rule the world instead of them? Surely this behavior is extreme for old Canaanite El, especially because he’s granting an outsider deity like Yahweh such authority to kill everybody else.

“Israel is “god contends” and does not necessarily need to indicate El. You are forgetting that El functions as both proper name and generic term both in Canaanite and in Israelite texts.”

I would think that if “El” occurs by itself, as a subject, surely it means THE El. Even Richard Elliott Friedman agrees (see his book on the Exodus) and I believe this is why Mark Smith believes Yahweh and El were identified very early on.

“If “inheritance” is a metaphor it must be describing God’s reservation of land… in which case it is completely nonsensical as a metaphor. “That reservation of land is as inheritance” is inherently contradictory in conception.”

Suppose I tell this story: “There was once a great king named John. The great king found a treasure, from which he gave out small shares to his squires. But in his generosity, he gave out the biggest share to little Johnny.”

The “gave out” in the second sentence is literal, while the “gave out” in the third is not. Sentence 3 uses the phrase in a loose and metaphorically-ironic way that communicates how ungenerous and selfish the king is, because he’s hoarding a big part of the dang treasure for himself. Similarly, in Deuteronomy 32, there is a metaphorical use of the term “inheritance” to highlight how special Israel is, because while Yahweh has parceled out other nations to other gods, Yahweh has “inherited” Israel for himself. He’s GIVEN it to himself. He’s KEPT it for himself.

“ “Their bones are hard as bricks” is a metaphor with “brick” functioning to describe the hardness.”

That’s a simile. Not a metaphor. The difference between the two is something you learn in first grade English!

And metaphors/similes do not need to work like this. If I say about someone, “They have a heart of stone,” I am not ascribing rockiness or actual hardness to their organ. Rather, I am saying the person is cruel. But on your logic, “stone” can’t mean anything like “cruel” because they’re such different concepts.

“Therefore “inheritance” cannot be a metaphor. Israel isn’t receiving anything. If your reading is correct and YHWH the highest god, Israel receives no inheritance.”

The nations, Israel included, are not receiving inheritances on either the “sons of Israel” or the “sons of God” reading, so how is this relevant to our discussion?

“If you want to argue metaphors, you’d better not do it with me… a person who has spent years in poetry classes in university lol.”

Bro, you couldn’t tell the difference between a simile and a metaphor…

Anyway, I think I’ll let you have the last word here. I’ll try to think about this material more, but I’m just not seeing eye-to-eye with you. At least not yet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

(1) Nice job copying the Hebrew from online. Why is it “straightforward” to read the head god as a part of his pantheon, when all ANE pantheons have the head god positioned outside of it? In fact, Michael Heiser himself has argued that God (YHWH) is outside of his council in Zech 3, meaning that this motif was known to them and used by them and taken for granted.

The simple answer is that it isn’t the plainest reading. By all counts, comparing this text to other divine council scenes inside and outside of the Bible, one comes away with Elohim as a lower tier deity. Comparing to Zech. 3 he comes off as an accuser within another deity’s council. And comparing to other scenes in ANE, he appears this way.

“Surely this behavior is extreme for old Canaanite El, especially because he’s granting an outsider deity like Yahweh such authority to kill everybody else.”

You clearly did not read the paper if this is one of the questions you are coming away with. El is not granting YHWH authority to kill everyone in the council (that is a gross misreading of the text too). Also, YHWH would not be an outsider, he would be one of the bene elim. He is one of El’s sons. If El is the speaking voice, I really want to know where he grants YHWH authority to kill the gods… he doesn’t. I’d also add this parallels Zech. 3 again… ha-satan does not speak in that passage either. It just says he renders accusations.

Your reading only works if you presume from the outside that the terms are the same and that the author is being subversive… instead of the far more evidenced conclusion that he is within his ANE context.

(2) “I would think that if “El” occurs by itself, as a subject, surely it means THE El. Even Richard Elliott Friedman agrees (see his book on the Exodus) and I believe this is why Mark Smith believes Yahweh and El were identified very early on.”

This is not necessarily the case at all. You should read some full studies on onomastics.

(3) “Suppose I tell this story: “There was once a great king named John. The great king found a treasure, from which he gave out small shares to his squires. But in his generosity, he gave out the biggest share to little Johnny.””

Your story would be absurd… because he isn’t giving himself anything. The “gave out” is meaningless and adds nothing, therefore it is just grammatical filler with no purpose. It conveys nothing because he gave nothing to himself in no sense of the word. You cannot “give” yourself anything in this sense. If I already own something, I cannot give to myself what I already possess. I cannot hand myself toilet paper, if toilet paper is in my hand.