Author: Gregory E. Sterling

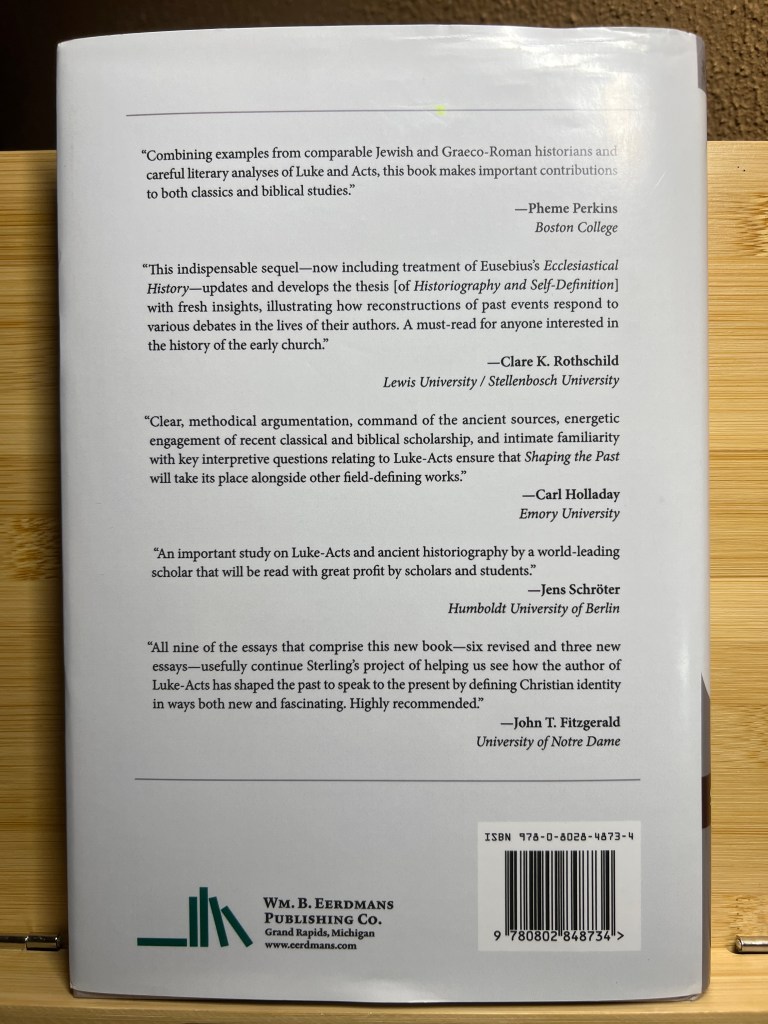

Title: Shaping the Past to Define the Present: Luke-Acts and Apologetic Historiography

Publisher: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company

Year: 2023

Page Count: 301 pages

Price: $44.00 (hardcover)

INTRODUCTION

To borrow from Qohelet, on the writing of the genre of the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles there will be no end (cf. Ecclesiastes 12:12). This is especially true of Acts, as Christy Cobb observes, “because of the inclusion and use of literary motifs such as prison breaks, shipwrecks, and the ‘we’ passages.”1 Cobb, for her part, identifies the presence of multiple genres in Luke-Acts and argues that the genre best suited to describe the duo is “the developing menippean genre,”2 a kind of hodgepodge of genres.3 Other scholars have referred to Acts as “collected biography”4 or as a “historical monograph”5 or as an ancient novel6 (to name a few). Among evangelical scholars, the preference tends to be something in the ancient historiography camp.7 Because genre informs how we read a text, this question is not a mere triviality. Flat readings of either Luke or Acts can lead to poor understandings of the Evangelist’s purpose.

Into this crowded space enters a new volume on the subject of genre in Luke and Acts: Shaping the Past to Define the Present: Luke-Acts and Apologetic Historiography (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2023). Written by Gregory Sterling, this volume serves as a follow up to his monograph Historiography and Self-Definition (Brill, 1992). In this more recent work, Sterling argues forcefully that Luke-Acts belongs to apologetic historiography, a genre he contends can be found in other ancient histories including Josephus’s Antiquities. In support of this, the author presents various strands of evidence, one of which we will examine shortly.

OVERVIEW

Following an introduction that defines “apologetic historiography” and lays out the purpose and plan of the project, our author discusses in ch. 1 the content, form, and function of the writings of Josephus, the author of Luke-Acts, and Eusebius. All three were keenly interested in narrating the story of a “people,” Jews in the case of Josephus and Christians in the case of Luke-Acts and Eusebius. Additionally, each was prompted by apologetic concerns to write. For example, Josephus, using Greek historians as a model, sought to “emphasize the antiquity of the Jewish people over against the relatively recent advent of the Western powers [i.e., Rome] in the Mediterranean” (p. 29), thereby giving them an air of respectability.

Chapter two considers the ways in which Greek historians wrote about non-Greek cultures and the reaction of those cultures to Greek assessments. Per Sterling, Josephus in Against Apion claimed “that there was a distinct tradition of Eastern historiography that was more reliable in recording antiquity than the Greek tradition” (p. 44). Whereas Greek authors tended to discount non-Greek accounts, Josephus (and others) responded that such cultural snobbery caused Greek history to be less than ideal. This is seen clearly in Greek historiographic practice: traveling to native lands to interview locals. But Eastern historians found this to be deficient and preferred instead to draw upon sources within their own traditions in their own languages, albeit rendering them into Greek. Such a phenomenon is part of apologetic historiography.

In ch. 3, Sterling queries the unity of Luke-Acts and argues that there are signs in the Gospel of Luke that its author was planning out the Acts of the Apostles. Specifically, our author posits that Luke’s alteration of Markan material suggests this. For example, whereas the Markan Evangelist cites Exodus 23:20, Malachi 3:1, and Isaiah 40:3 as Isaian (Mark 1:2-3), in his redaction of Mark the Lukan Evangelist omits both the text from Exodus and the text from Malachi, choosing instead to continue the quotation of Isaiah 40 all the way down to a key phrase: “and all flesh shall see the salvation of God” (Luke 3:6; cf. Isaiah 40:5 LXX). Why does Luke alone do this? Sterling suggests that Luke, because he has largely omitted Jesus’s gentile mission, has opted instead to make that mission the focus of Acts. And so, at the end of the book he has the apostle Paul in Rome declare, “Let it be known to you then that this salvation of God has been sent to the Gentiles; they will listen” (Acts 28:68). This and other evidence lead Sterling to conclude that not only were the books of Luke and Acts written by the same author, they are a two-volume work belonging to the same genre of apologetic historiography.

How does the LXX fit into all of this? That is the subject of ch. 4. Sterling first examines Josephus’s relationship to the LXX, noting that the Jewish historian relied heavily upon the Letter of Aristeas in volume 12 of Antiquities while at the same time undermining the Greek translation’s status so that his audience would prefer his translation of the Jewish scriptures over it. This, our author contends, was not the project of the author of Luke-Acts who instead of seeing himself in competition with the LXX chose to continue and imitate it. Sterling finds precedent for this in various Greek historians who not only imitated their predecessors but in some instances saw fit to continue where they had left off.

Chapter five looks at the speech of Stephen found in Acts 7. In particular, Sterling tries to situate the monologue in its historiographic context as one modeled after Hellenistic Jewish historians like Cleodemus Malthus, Pseudo-Euoplemus, and more. One of the goals of Stephen’s speech is to legitimate the Christian mission to the Diaspora and our author posits “the author of Acts and these Hellenistic Jews knew and used similar exegetical traditions when they retold the LXX” (p. 120). To that end, Sterling identifies a number of places where this is evident. Central to this is the idea that Stephen’s speech employs traditions that “make claims of legitimation for locales outside Jerusalem and Judea” (p. 122) by focusing on regions outside of those areas. The temple of Yahweh, as important as it was, was not the only place the god of Israel could be found at work.

Stephen’s speech in Acts 7 is not the only extended monologue in the Acts of the Apostles. The apostle Paul offers one in Acts 13, the subject of ch. 6 of Sterling’s work. As our author notes, the speech appears at the beginning of Paul’s mission in chs. 13-28 and is “saturated with the language of the LXX,” centering God as the primary actor in Israel’s history by making him the subject of nearly every verbal form in the speech. The exception is David and for good reason: it not only “calls attention to him” but it points the way to the second half of Paul’s speech wherein the apostle makes use of Davidic texts to show Christ’s death and resurrection as the fulfillment of Holy Writ. Sterling also doubts the historicity of Paul’s speech, contending instead that it is the creation of the Lukan author “intended to illuminate the narrative” (p. 150) and placed in that specific literary locale “to defend the Gentile mission” (p. 151).

In ch. 7, our author looks at the death of Jesus in the Lukan Gospel and the role that narratives about the death of Socrates played in its composition. Sterling notes that Socrates became a model in antiquity, serving as both an example of a noble death and “the lens by which the deaths of later philosophers were viewed” (p. 166). The influence is felt not only in Greco-Roman texts but even Jewish stories about martyrs. The Lukan Evangelist picked up the Socrates motif and put it to good use, not only heavily redacting the Markan version of events with its Jesus in despair but offering to his readers a Jesus whose life and, more importantly, whose death served as models to follow. Sterling writes that Luke “carefully reworked the death of Jesus at critical places to remind the hearer/reader of the paradigmatic martyr of his society, Socrates,” doing so “to make [his] story intelligible and acceptable within the framework of that larger culture [i.e., the Greco-Roman world]” (p. 183).

The final chapter examines two charges often leveled at early Christ-followers: that they were “country bumpkins” who disturbed the social order and participated in obscene rituals. Sterling documents both the pagan critique that originated these claims as well as how the author of Luke-Acts encountered and dealt with them in his own writing. For example, we find in Acts 4 the narrator reporting that the religious authorities found it hard to believe Peter and John could speak with such eloquence because “they were uneducated and ordinary men” (Acts 4:13, NRSV). In response to this, Luke “went out of his way to note the higher social status of select members of ‘the Way’” (p. 217), including figures like the Ethiopian official from Acts 8, the business woman Lydia in Acts 16, and even a Roman centurion in Acts 10. Sterling writes, “I cannot imagine the author of Acts writing the words of the narrative’s protagonist [i.e., Paul] when describing the social position of converts: ‘not many wise by human standards, not many powerful, not many born to noble families’ (1 Cor 1:26). On the contrary, the author of Acts made the most out of the little that there was” (p. 219). The volume closes with a conclusion that wraps up Sterling’s work followed by a bibliography and indices.

ASSESSMENT

I must admit that Shaping the Past to Define the Present was hard to put down. Two things contributed to its appeal: the clarity with which Sterling wrote and his grasp and use of ancient sources that included not only the biblical corpus but Greco-Roman texts as well. As is the case with all ancient texts, Luke-Acts was not written in a vacuum. It did not appear ex nihilo, as it were. Instead, Luke-Acts fits into a particular genre of writing Sterling calls “apologetic historiography.” The term sounds fancier than it is. In brief, apologetic historiography is the attempt by conquered peoples to tell their own stories using their own traditions as a means of self-definition but doing so in hellenized form to be consumed by the wider Greco-Roman world. Various texts fit into this genre, though our author finds Josephus’s Jewish Antiquities to be an example par excellence and uses it as a way of assessing genre in Luke-Acts.

Luke-Acts or Luke and Acts?

Before we continue, something should be said about the nature of the relationship between the two texts. That the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles were written by the same author seems almost without question.8 That author casts the Lukan Gospel as ho prōtos logos (Acts 1:1), rendered in the NRSV as “the first book.” This implies that Acts is ho deuteros logos, a second book and in some sense a sequel. The fact that the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles do not appear together on a single scroll speaks to the limits of the material available to the Evangelist. Since the length of the average scroll was only thirty-five feet, authors were forced to turn lengthy works into multiple volumes.9 Given the respective lengths of Luke and Acts, it is no surprise that two scrolls were needed.10

What can be inferred from this? Do the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles make up a single work of a single genre divided into two major sections? Or are they two separate works in two separate genres? In other words, should we speak of Luke-Acts or Luke and Acts? Complicating these questions are two further considerations.11 The first is one familiar to anyone who remembers from Sunday School the order of books in the New Testament canon. It begins with the Gospel of Matthew, continues to the Gospel of Mark, then to the Gospel of Luke, and then to the Gospel of John. The Acts of the Apostles is fifth in canonical order, bridging the Gospels on one side and the Pauline epistles on the other. This order, though not universal in early Christianity, seems to be dominant. One of the earliest witnesses to this can be found in the third century CE manuscript P45. Though fragmentary and inclusive of only material from the first five books of the New Testament, it attests to the order with which we are familiar: Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, and Acts.12 Similarly, the so-called Muratorian Canon,13 a Latin text that includes a partial listing of New Testament documents as well as works that did not ultimately make it into what would become the canon, has the order of books as Luke, John, and then Acts.14 This is despite the fact that it attributes both the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles to Luke. The church historian Eusebius also lists the books of the New Testament in the order with which we are generally familiar: “And here among the first must be placed the holy quaternion of the Gospels; these are followed by The Book of the Acts of the Apostles” (Ecclesiastical History 3.25.1).15 Over and again, we find that despite being attributed to a single author and despite the text of Acts referring to itself implicitly as the second of a two-volume work, Luke and Acts were separated, typically by John’s Gospel.

The second consideration is perhaps less familiar to both of my readers: the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles have had two very different textual trajectories. Mikeal Parsons makes this point in his commentary on Acts. First, he quotes Bruce Metzger who opens his section on the Acts of the Apostles in A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament by writing, “The text of the book of the Acts of the Apostles circulated in the early church in two quite distinct forms, commonly called the Alexandrian and the Western.”16 Parsons follows it up with a poignant observation: “The same has not, and indeed cannot be said about Luke’s Gospel.”17 Examples of the differences between the two text families abound but space does not permit more to be said here.18 The key takeaway is that such a phenomenon is odd if Luke and Acts circulated together. Parsons writes,

The little evidence that we do have, then, does not suggest that these two documents, Luke and Acts, were “published” together by Luke as one volume or even published at the same time, only later to be separated from one another with the emergence of the fourfold Gospel. Rather, the manuscript traditions suggest two distinct transmission histories, one for the Gospel and one for Acts. This implies at least that the two were published and disseminated separately, and quite probably at different times.19

So, it’s Luke and Acts then, not Luke-Acts. Or is it?

Two Scrolls, One Work

Though Sterling does not address the aforementioned issues in full in this volume, he does offer some tantalizing evidence that indicates that, whatever happened to Luke and Acts later in Christian history and textual transmission, the author of Luke intended for Acts to be read alongside the Gospel. It is not merely that Acts implies that it is itself a second volume; there are other clues teased out by Sterling that point in this direction. Chapter three, “The First History: The Literary Relationship between Luke and Acts,” discusses one of these clues.

Sterling begins with the phenomenon of ancient titles, noting that Pliny the Elder preferred titles that were suited for the work in question and that other ancient historians seemed to agree. One-word titles abounded: Aegyptiaca, Antiquities, Library, and more. But sometimes an author preferred to not use a title, a phenomenon known all too well to New Testament scholars. The canonical Gospels all lack formal titles and the titles that we do have with their attributions to specific individuals connected in some way or another to the early Jesus movement are innovations of the second century CE.20 This lack of titles, Sterling argues, had the “unfortunate result” of leading “to the separate circulation of the two related works: the Third Gospel and the work that we have come to know as the Acts of the Apostles” (p. 63). Combining the material limits under which the Lukan author wrote the two volumes as well as his choice not to use titles, Sterling’s argument seems sensible. A prima facie reading of Acts could easily lead a reader to believe that it is a much different work than Luke. After all, the first volume is the story of Jesus from birth to death to resurrection to ascension. The second volume, though it has an expanded ascension scene, tells the story of the early Christ-following assemblies under the leadership of the apostles and concluding with the work of Paul. How are these not two different kinds of works?

Indeed, as Sterling notes, one consequence of separating Luke from Acts is that the question of genre becomes more complicated. Many scholars consider the Gospel of Luke to be a type of bios while Acts becomes a general historiographic work.21 “This would mean,” writes Sterling, “that the first history of Christianity was a history of the church from its birth in Jerusalem to the imprisonment of Paul in Rome” (pp. 64-65). But our author thinks this is precisely not the case. Rather, Luke and Acts “represent independent scrolls of a single work” resulting in “a history of Christianity beginning with Jesus as the founder and continuing through the apostles to Paul” (p. 65). And because for Sterling Luke-Acts belongs to the genre of apologetic historiography,22 the program of the Evangelist begins not with the second book – the book of Acts – but with the first, the Lukan Gospel. He writes, “The consequences of thinking of Luke-Acts in this tradition [i.e., apologetic historiography] are greater for our understanding of Luke than they are for our perception of Acts. Luke is no longer a work about Jesus of Nazareth, but the first half of a story about a movement that began with him” (p. 65).

This may in some ways be a hard pill to swallow. From beginning to end, the third Gospel is a story about Jesus of Nazareth. It derived much of its material from the Gospel of Mark and probably the Gospel of Matthew, two works quite obviously about Jesus. How could it possibly be that the Gospel of Luke isn’t a story about Jesus?

The Past is Prologue

One reason to think Sterling is on to something is how the Gospel of Luke begins, not with a story about Jesus but a story about John the Baptist. John plays an important role in all of the canonical Gospels but it is only in Luke’s Gospel that we have a fuller backstory for the prophet in the form of an infancy narrative. What is interesting about this is the contrast in terms of literary quality between the prologue of 1:1-4 and what follows in the rest of chs. 1-2. The prologue is written in “a stylistically polished” form of Greek “that exhibits linguistic and structural parallels to other Jewish and Greco-Roman historical and learned texts.”23 The nature of this prologue has been variously discussed, with Loveday Alexander’s The Preface to Luke’s Gospel: Literary Convention and Social Context in Luke 1.1-4 and Acts 1.1 being the classic work on it.24 Sterling does not spend much time discussing the prologue at all in this volume, but he does comment on the importance of the section that follows. For, while the Greek of the prologue shows off Luke’s education and rhetorical sophistication, the rest of chs. 1-2 shows his affection for and conscious imitation of the LXX.

In ch. 4 of our author’s work, this point is made all the more clear. There he shows that in contrast to Josephus who on some level sought to rewrite the LXX in his Jewish Antiquities, the Lukan Evangelist instead saw the LXX as prelude to the story he was telling in Luke-Acts. He was continuing Israel’s story. Sterling writes, “He wrote in the style of the LXX in the early chapters of his first scroll in order to create a seamless transition from the LXX to his own history” (p. 104). The choice to begin with John the Baptist is a natural one because in Luke’s source material he is a bridge between ancient Israel on the one hand and the Jesus movement on the other. He is, in the words of Sterling, “the transitional figure” between the two (p. 231).25 Luke picks up on what his sources have laid down and casts John’s miraculous and unexpected conception and birth along with his unprecedented relationship (by blood) to Jesus, in Greek that tells the stories in the accent of the LXX.26

By telling these stories in this way, the Evangelist is signaling that Jesus’s story isn’t something out of the blue and without precedent. Rather, he is connecting Jesus through John to the entire history of Israel. Additionally, Luke is the only one of the Evangelists to feature a scene depicting what happened to Jesus after the resurrection. In the Markan and Matthean Gospels, one is left to wonder where Jesus went. Not so in Luke’s Gospel as he has solved the problem: Jesus leaves this world. The mission of Jesus then becomes the mission of his followers. The story continues! Jesus is of course central to this mission, but its motivation is stirred up by the holy spirit, the same spirit that filled John the Baptist (Luke 1:15).27

Redacting Mark, Planning Acts

Sterling observes that the Lukan Evangelist chose to do something with his written works that the other Evangelists did not. Mark never mentions either the creation of Christ-following assemblies (ekklēsiai) or the giving of God’s spirit (pneuma). Matthew mentions the former (Matthew 16:18) but not the latter. John mentions the latter (John 20:22) but says nothing about the former. The Lukan Evangelist, however, does both by keeping the story of the assemblies and the giving of the spirit for his second volume, the Acts of the Apostles. “It is this point,” Sterling writes, “that may help us to solve the issue of the nature of the relationship between the two scrolls” (p. 65). Our author suggests that there is evidence Luke planned the contents of Acts while writing the Gospel. But this evidence is not to be found in the ways in which Acts parallels or echoes the Gospel but in how he “altered pre-existing source material in such a way that it appears that he is setting the readers up for Acts” (p. 65). To see whether this take is plausible, Sterling proposes a test case: “Did Luke edit Mark with Acts in mind?” (p. 66)

Our author presents to his readers not a single text but four by which this hypothesis can be tested. The first example can be found in how Luke (Luke 3:4-6) treats Mark’s composite quotation in Mark 1:2-3. The Markan Evangelist stitched together three texts: Exodus 23:20, Malachi 3:1, and Isaiah 40:3. Though only the second half of the prophetic material, found in v. 3, comes from Isaiah, Mark nevertheless attributes it all to the famous prophet. In his redaction of Mark, Luke makes significant changes, beginning with removing the material from Exodus and Malachi. The quote from Isaiah is truly from Isaiah.28

The other significant change Luke makes is he expands the citation from Isaiah 40 to include not only v. 3 but also the next two verses, terminating with the words “and all flesh shall see the salvation of God [to sōtērion tou theou].” Luke uses here not the Masoretic Text, but the LXX. In the MT, v. 5 reads, “Then the glory of the LORD shall be revealed, and all people shall see it together, for the mouth of the LORD has spoken.” There is no mention of “salvation” at all. But in the LXX, v. 5 reads, “And they will all see the glory of the Lord, and all flesh will see the salvation of God, for the Lord has spoken” (my translation). Sterling notes that Luke’s decision to extend the quotation he found in Mark is consonant with the Evangelist’s tendency to use terms from the “salvation” family of words like sōtēr (“savior”; e.g., Luke 1:47, Acts 5:31), sōtēria (“salvation”; e.g., Luke 1:69, Acts 4:12), and sōtērion (“salvation”; e.g., Luke 2:30, Acts 28:28).

Why for Sterling does any of this matter? The key is “all flesh.” The theme of universal salvation appears throughout Luke-Acts, but it is emphasized at the very end of the work when an imprisoned Paul in the city of Rome says, “Let it be known to you then that this salvation of God [to sōtērion tou theou] has been sent to the Gentiles; they will listen” (Acts 28:28). Two things are striking about Paul’s words here. The first is the obvious one: he uses the phrase from Isaiah 40:5 LXX that Luke already used in Luke 3. The second is that Paul’s conclusion comes after he too has quoted a passage from Isaiah, specifically Isaiah 6:9-10 LXX. This is surely intentional on Luke’s part, but what does it mean? Our author queries whether Paul’s words are echoing Luke 3 or if Luke 3 is setting up Acts 28. “I suggest the latter is more likely,” he writes (p. 68). He thinks that “the more probable explanation” is that “because the Gospel of Luke does not include a mission to the Gentiles; this mission is narrated in Acts. This inclusion of the Gentiles at this early stage of Luke suggests that the evangelist had planned to write the story of the mission to the Gentiles” (my emphasis).

At this juncture, Sterling transitions to his second test case: the delay of the mission to the gentiles. To appreciate this, readers must take stock of how the author of the third Gospel reworked one of his primary sources – the Gospel of Mark.29 With some of this reworking, you may be familiar. For example, Jesus’s rejection at Nazareth which in Marks takes place in ch. 6, well into his ministry, is in Luke’s Gospel moved to the beginning and expanded (Luke 4:16-30). Additionally, Jesus’s anointing in Mark happens in ch. 14 during the week of his passion but in Luke it happens in ch. 7, well before Jesus even began his approach to Jerusalem.

But there are even more dramatic examples of Lukan reworking. One of them concerns the various journeys that the Markan Jesus takes. Sterling lays them out in a chart on pp. 68-69 and notes that for the Markan Evangelist they serve “to justify the presence of Gentiles in the Markan community by postulating a mission to them by Jesus” (p. 69). Earlier, our author noted that Evangelists like Matthew and John portray the Christ-following assemblies as being rooted in the ministry of Jesus himself. For Mark, the same is true, albeit in this case the focus is on the mission to the gentiles, something that happened in the wake of Jesus’s death. For Luke, however, that story is reserved for Acts. To that end, the Evangelist has made significant alterations to Mark’s version of events.

The first journey Jesus takes in Mark is found in Mark 4:35-5:21. He and his disciples cross the lake (4:35), end up in the country of the Gerasenes on the other side (5:1), and cross the lake again (5:21). How does Luke handle this journey? Jesus and the disciples cross the lake (Luke 8:22), end up in the country of the Gerasenes (8:26), and return from where they came (8:37). This sure sounds like Mark, doesn’t it? It does, but Sterling notes something found in Luke that is not found in Mark. In v. 26, the text says that they arrived “at the country of the Gerasenes, which is opposite Galilee.” By this, Sterling opines, Luke “wanted to incorporate the incident but did not want to let it go without explaining that it was still within the basic orb of Jesus’s Galilean movements. It appears that the author knew that this was outside of Galilee but emphasized that it was beside the lake as a way to minimize its significance” (p. 70). In other words, Jesus may have gone to gentile territory but he made no deep entry into it. Penetrating gentiles spaces is what happens after Jesus commissions the eleven before his ascent to heaven. This concern for restricting Jesus’s mission is also seen in Luke’s alteration of Mark 5:20. Rather than having the healed demoniac go to the Decapolis, a group of ten cities that were largely gentile, to declare what Jesus had done, Luke says simply that the man returning to “the city” – singular – to proclaim what happened (Luke 8:39).

The next journey in Mark is found in 6:45-53. In this scene, following the feeding of the five thousand, Jesus sends his disciples to go to Bethsaida by boat while he remains on land. An adverse wind comes upon the disciples as they’re rowing and as they strain to keep the ship going they see Jesus strutting across the waves in a show of divine power. When the journey is complete, they end up at Gennesaret, an area on the northwestern shore of the lake. How does Luke handle this material? He doesn’t. The Evangelist has removed all of the material found in Mark 6:45-8:26 – Luke’s “Great Omission.” This includes Mark’s second, third, and fourth journeys. Why get rid of all this material?

Sterling’s answer comes in two parts. First, he notes that Luke exhibits an allergic disposition toward Markan doublets, for example, keeping Mark’s first boat scene (Mark 4:35-41; Luke 8:22-25) but removing the second (Mark 6:45-52) or retaining the feeding of the five thousand (Mark 6:32-44; Luke 9:10-17) but omitting the feeding of the four thousand (Mark 8:1-10). “While Luke can have duplicates,” he writes, “he typically does not like to repeat whole stories in the way that Mark did” (pp. 71-72). But Sterling points out that this only partly answers the question since some material of the Great Omission is not part of a doublet. For example, where is the pericope found in Mark 7 involving the dispute over hand washing? It is gone in Luke’s Gospel. Why?

This leads us to the second part of the answer. When the Lukan Evangelist realigns with the outline of Mark’s account, the convergence is at the story of Peter’s confession that Jesus was the messiah. But something interesting has happened in Luke’s redaction of Mark. Whereas the second Gospel places this pivotal moment in Caesarea Philippi, a locale outside of Galilee (Mark 8:27), Luke drops the reference to Caesarea Philippi and places the confession in Galilee.30 From this Sterling gets the impression that Luke has altered his source’s version of events to keep Jesus in Galilee. He writes, “I suggest that Luke omitted Mark 6:45-8:26 because he knew that he would deal with the Gentile mission in Acts. It would have been out of place in his gospel and ruined the point that he wanted to make in his second scroll” (p. 72).

Sterling offers two more examples of how Luke has altered his source in a bid to keep material about the gentile mission for his second volume, but space does not permit a rundown of those examples. And while I am not entirely convinced of Sterling’s thesis, he is undoubtedly correct that Luke has done some heavy redaction with his Markan source and he is keen on keeping Jesus in Galilee and away from gentile spaces in general. Whether this is a sign that the Evangelist was thinking of his second volume is not clear to me, even if the proposed evidence is tantalizing.

CONCLUSION

I’ve devoted a significant part of this review to specific material in Sterling’s book. This was done not only because of my fascination with the relationship of Luke and Acts as well as how the later Evangelists treated their source in the Gospel of Mark, but also to give readers examples of the kinds of arguments and points raised by Sterling in this excellently written volume. As a lay person – a mere amateur – I am conscious of my own limitations and am well aware that I have virtually nothing original to contribute to the field of biblical studies other than to testify to my own views. My aim in writing reviews – and even blog posts – is to point those who stumble across my blog to quality resources (or, in some cases, things to avoid). In this case, I hope readers who are interested in the genre of Luke-Acts pick up Sterling’s Shaping the Past to Define the Present because whether they are convinced by all he says or not they will at least find intriguing arguments made by a scholar with a command of the material, an eye for detail, and the ability to express it in understandable ways.

ENDNOTES

1 Christy Cobb, Slavery, Gender, Truth, and Power in Luke-Acts and Other Ancient Narratives (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 16.

2 Cobb, Slavery, Gender, Truth, and Power, 16.

3 For a discussion of menippea, see Cobb, Slavery, Gender, Truth, and Power, 42-53.

4 Sean A. Adams, The Genre of Acts and Collected Biography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

5 Joseph A. Fitzmyer, The Acts of the Apostles: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, The Anchor Bible (New York: Doubleday, 1997), 49.

6 Richard I. Pervo, Profit with Delight: The Literary Genre of the Acts of the Apostles (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1987). Cf. Richard I. Pervo, Acts: A Commentary, Hermeneia Commentary Series (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2009), 14-18.

7 Craig S. Keener, Acts: An Exegetical Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012), 1:89.

8 Authorial unity for Luke-Acts has various strands of evidence: the prologues addressed to Theophilus (Luke 1:3, Acts 1:1), the reference to a “first book” in Acts 1:1 that was about Jesus’s life and ministry, the similarity of vocabulary and themes, and much more. For a defense of the unity of Luke-Acts, see Patrick E. Spencer, “The Unity of Luke-Acts: A Four-Bolted Hermeneutical Hinge,” Currents in Biblical Research 5 no. 3 (2007), 341-366. However, there are dissenting voices, e.g., Patricia Walters, The Assumed Authorial Unity of Luke and Acts: A Reassessment of the Evidence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

9 Bruce M. Metzger, Manuscripts of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Greek Paleography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981, 16.

10 See Arthur G. Patzia, The Making of the New Testament: Origin, Collection, Text & Canon (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2011), 148. Drawing on the work of David Aune, Patzia writes that the Gospel of Luke has 19,404 words appearing on 2,900 lines and that the book of Acts has 18,374 words on 2,600 lines and, therefore, “each book would have filled an entire scroll.”

11 For an extended discussion, from which much of the material I have written is derived, see Mikeal C. Parsons, Acts, Paideia Commentaries on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008), 12-14.

12 Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, translated by Erroll F. Rhodes, second edition (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1989), 98-99. For images of P45, see “P45,” manuscripts.csntm.org.

13 To read the Muratorian Fragment, see “Muratorian Fragment,” bible-researcher.com. For an overview of the Fragment, see Bruce M. Metzger, The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), 191-201.

14 The beginning of the list in the Fragment is lost but presumably began with Matthew and Mark.

15 Translation taken from Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History, translated by C.F. Cruse (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1998).

16 Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, second edition (Stuttgart, German Bible Society, 1994), 222.

17 Parsons, Acts, 13.

18 Readers are directed to the section on Acts in Philip W. Comfort, New Testament Text and Translation Commentary (Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., 2008), 325-433. There they will find scores of examples wherein the Western text has alternate, expanded readings in multiple places.

19 Parsons, Acts, 13-14.

20 On the anonymity of the Gospels, see Armin D. Baum, “The Anonymity of the New Testament History Books: A Stylistic Device in the Context of Greco-Roman and Ancient Near Eastern Literature,” Novum Testamentum 50 (2008), 120-142. On the titles themselves, see the discussion in Petr Pokorny, From the Gospel to the Gospels: History, Theology and Impact of the Bible Term ‘Euangelion’ (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2013), 186-191.

21 Bart Ehrman, for example, writes, “In terms of overall conception and significant themes the two volumes [of Luke and Acts] are closely related, but their different subject matters required the use of different genres, one a Greco-Roman biography and the other a Greco-Roman history.” See Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings, sixth edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 154.

22 Sterling defines apologetic historiography as “the story of a subgroup of people in an extended prose narrative written by a member of the group who follows the group’s own traditions but hellenizes them in an effort to establish the identity of the group within the setting of the larger world” (p. 5).

23 See the comments on this passage by David L. Tiede (revised by Christopher R. Matthew) in The HarperCollins Study Bible, revised edition, edited by Harold Attridge (New York: HarperOne, 2006), 1761.

24 Loveday Alexander, The Preface to Luke’s Gospel: Literary Convention and Social Context in Luke 1.1-4 and Acts 1.1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993). Sterling refers to Alexander’s work as “the single most important treatment” (p. 21n55). For another view of this section, see e.g., John Moles, “Luke’s Preface: The Greek Decree, Classical Historiography and Christian Redefinitions,” New Testament Studies 57 (2011), 461-482.

25 Cf. Joel Marcus, John the Baptist in History and Theology (Columbia, SC: University of South Caroline Press, 2018), 12-13.

26 On the influence of the LXX on Luke’s infancy narratives, both directly and indirectly via sources, see Chang-Wook Jung, The Original Language of the Lukan Infancy Narrative (London: T&T Clark, 2004). Jung’s work looks at whether Luke was using “Semitic” sources, written in Hebrew or Aramaic, or if he was dependent on sources in Greek that were influenced by the LXX (in addition to the LXX).

27 The holy spirit is a significant actor in the drama of Luke-Acts. On its role in Acts, see Daniel Marguerat, The First Christian Historian: Writing the ‘Acts of the Apostles’ (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 109-128.

28 Sterling notes that Luke is fond of correcting Mark’s mistakes. The classic example, and the one that Sterling himself gives (p. 67n31), comes from a controversy narrative found in Mark 2/Luke 6. Whereas the Markan Jesus situates the story of David eating from the bread of the Presence “when Abiathar was high priest” (Mark 2:26), an outright historical error (cf. 1 Samuel 21:1-9), Luke drops the reference altogether (Luke 6:4).

Another example of this can be found in the title attributed to Herod Antipas. In the Gospel of Mark, he is a king (Mark 6:14). It is true that Antipas aspired to be one (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 18. 240-56; cf. John R. Donahue and Daniel J. Harrington, The Gospel of Mark, Sacra Pagina [Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 2002], 195), but he nevertheless was not a king. He was, as Josephus notes, “a tetrarch of Galilee and Perea” (Antiquities 18.240). Luke agrees and refers to as “king” only Herod the Great – since he was (Luke 1:5) – and to Herod Agrippa (Acts 12:1) since he too was a king (cf. Antiquities 19.328-331). Herod Antipas, on the other hand, is spoken of as “the tetrarch” (e.g., Luke 3:19; Acts 13:1).

29 On Luke’s creative restructuring, see L. Michael White, Scripting Jesus: The Gospels in Rewrite (New York: HarperOne, 2010), 319-326.

30 White (Scripting Jesus, 449) explains that the “geographical framework” of Luke’s Gospel differs from either Mark or Matthew. In Mark’s Gospel, the feeding of the five thousand and the confession of Peter do not happen in close succession. Additionally, the feeding story occurs away from Bethsaida (cf. Mark 6:45). In Luke’s Gospel, the Evangelist has set the scene in Bethsaida, though he reveals he’s reworking Mark by the implausible statement that Jesus, the disciples, and the crowd were “in a deserted place.” (See Mark Goodacre, “Fatigue in the Synoptics,” New Testament Studies 44, no. 1 [January 1998], 50-51.) The result of Luke’s changes to the narrative found in Mark is that now the feeding and the confession occur back-to-back in Galilee.

amazing review! and reaaaaally interesting info!

also wanted to thank you for your blogs, they introduced me to the whole new world of redactional criticism (which i’ve only previously heard from rants from lydia mcgrew)!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gregory Sterling’s review of “Shaping the Past to Define the Present: Luke-Acts and Apologetic Historiography” provides a compelling analysis of the ways in which the author navigates the complex relationship between historical inquiry and religious apologetics in the context of Luke-Acts. By examining how the author of Luke-Acts shaped historical narratives to serve theological and rhetorical purposes, Sterling offers valuable insights into the intersection of faith and historical scholarship. This review not only deepens our understanding of the ancient world but also prompts critical reflection on the methods and motivations behind historical writing. Sterling’s examination reminds us of the enduring importance of considering the ideological underpinnings of historical texts, particularly in religious contexts, and underscores the ongoing relevance of Luke-Acts as a rich source of both historical and theological inquiry.

LikeLike