INTRODUCTION

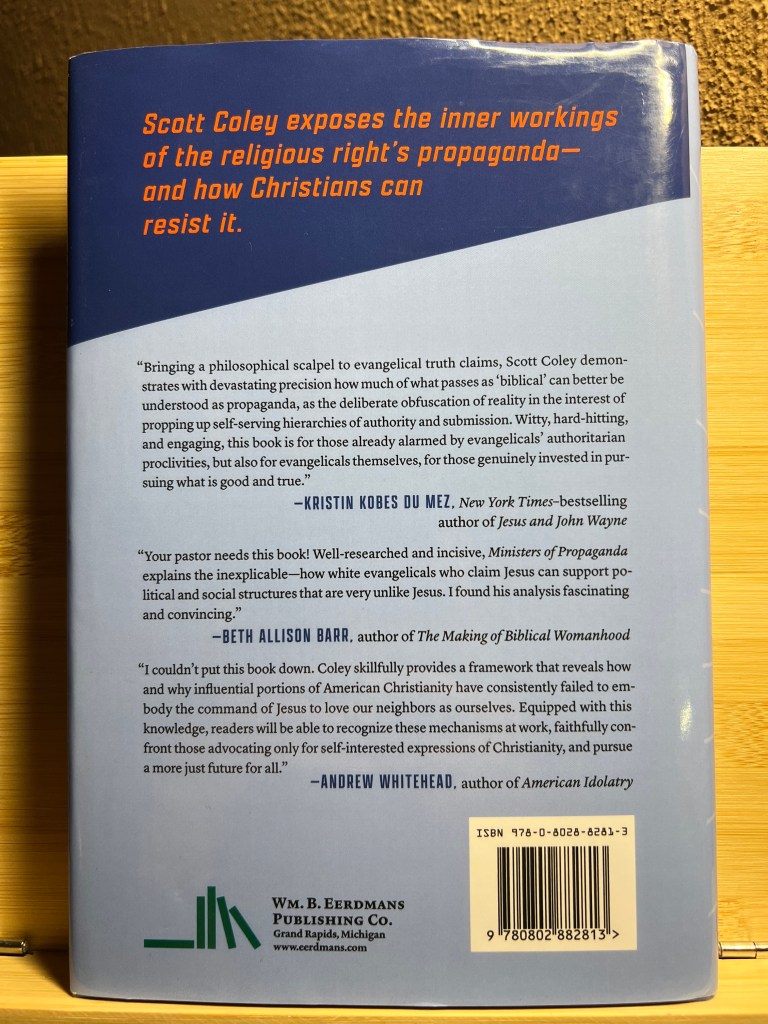

Scott Coley, a philosopher teaching at Mount St. Mary’s University in Maryland, has written a thought-provoking volume on the religious right entitled Ministers of Propaganda: Truth, Power, and the Ideology of the Religious Right (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2024). In it he takes on not only the misogyny and racism inherent in many conservative ideals, but he also castigates young earth creationism and offers a modern history of the right that lays bare its foundations in anti-democratic ideals. He appeals to primary sources and offers an analysis of these “ministers of propaganda” that is as stinging as it is on the mark.

SUMMARY

In the volume’s introduction, Coley lays out two, self-reinforcing “scandals” plaguing American evangelicalism: virulent anti-intellectualism and malevolent social practices. Whether it is for white supremacy or gender inequality, evangelical leadership employs rhetorical propaganda as a bulwark against anything that might threaten its desired hegemony over American Christianity and society at large. For example, pro-slavery Christians and, in a later period, segregationists could appeal to the Bible to support their desired social structuring. This “hermeneutic of legitimization” (p. 9) gives abhorrent positions the benefit of divine approval, insulating bigots and misogynists from criticism as well as providing them with fodder to attack any who would disagree. Our author refers to this and other attempts to strangle society by means of Christianity as “Christo-authoritarianism” which, he contends, “uses the resources of Christian theology to underwrite its authoritarianism” (p. 12).

But what underwrites that theology? In ch. 1, our author considers “common sensism,” the idea that everyday people have the resources within them to make sense of the world. “[N]o such faculty exists,” writes Cole (p. 20), and this is evident in the contradictory ways evangelicals have handled such morally fraught topics like slavery and abortion as well as hermeneutics itself. One of the more interesting junctures in which common sensism and hermeneutics meet is that of gender hierarchy. Our author observes that so-called complementarians will appeal to the Bible’s purported clarity in a bid to argue for patriarchy, all the while ignoring or downplaying specific biblical texts that argue otherwise and failing to appreciate that their arguments work equally well in support of slavery. The appeal to “common sense” readings of the Bible are, therefore, a type of propaganda, as are appeals to the Bible’s “authority.”

Chapter 2 is a discussion of racial hierarchy, specifically the disparities that exist that are either ignored or denied by white hegemony. For example, the “prevailing economic paradigm of the religious right” is the view that the United States is a meritocracy (p. 54). Those who enjoy wealth do so because of moral and spiritual virtues they possess in abundance; the poor, on the other hand, have a dearth of such virtues. Coley demonstrates that this is a pernicious farce, surveying United States history to show that systemic racism has been part and parcel of our country for generations and that, despite the language of “colorblindness,” the effects of such “implicit white supremacy” persist (pp. 74-78). The language of meritocracy, then, becomes a form of propaganda which, when coupled with “colorblindness,” manages to provide cover for the continuation of racial hierarchy while denying such hierarchy exists.

In ch. 3, the volume examines the phenomenon of young earth creationism. While other forms of creationism exist (e.g., Day-Age, Framework, etc.), Coley notes that young earth creationism sets itself apart by arguing that the cosmos and everything in it was created in the span of 144 hours recently and that the narrative found in Genesis 1 is a historical account of that creation. Surveying the work of young-earthers like John MacArthur and Albert Mohler, our author looks at the objections often raised against other forms of creationism, noting that in understanding a biblical text, interpreters should prefer “principled literalism” to the flat reading espoused by young-earthers. He also takes issue with what he calls “the Assumption,” the idea that “the only reason a Christian would reject the young-earth interpretation of Genesis is that they trust modern science more than Scripture” (p. 106).

The Assumption becomes important in ch. 4 wherein our author looks at the “culture war machine.” By arguing that their brand of creationism is the “biblical view,” young-earth creationists not only denigrate experts that disagree, but they also find themselves in a rich cultural environment in which they can also take on the secular, “godless” world. Coley notes how easily creationist gurus like Ken Ham lapse into confirmation bias while attacking experts with relevant credentials. Ham’s bifurcation of science into “historical” and “observational” is symptomatic of this since it overlooks the way in which science is inherently historical, in large part due to its inductive methodologies. Illustrative are ice cores which exhibit annual rings, many of which stretch back in time farther than young earth creationists allows on their “biblical view.” At the end of the chapter, Coley demonstrates that young earth creationism is part of a longer tradition of anti-intellectualism rampant in American evangelicalism.

Chapter 5 opens with the “conservative dilemma”: “how to recruit enough popular support to win elections while preserving the interests of relatively few voters at the top of the existing social order” (p. 136). As Coley goes on to explain, conservatives dealt with this by means of voter suppression (particularly of minorities) and by convincing middle- and working-class voters that their status within the status quo would be best preserved by voting against their own socio-economic interests. Tracing the historical narrative onward from the period of Reconstruction, our author shows that conservatives worked actively against civil rights and, when that failed to work, found other means to retain white supremacy. Whether it was Nixonian emphasis on “law and order” or Reaganite language about so-called “welfare queens,” conservatives did what they could to stoke racial divides with the unsurprising result of increased economic inequality and racial resentment. And in all of this, evangelicals often gave their full-throated support.

The penultimate chapter, ch. 6, covers the subject of Christo-authoritarianism and its political and cultural influence. Citing the work of scholar of religion Lauren Kerby, Coley notes how adherents to Christo-authoritarianism identify both as founders and victims. Ideologically, they view themselves as being in continuity with a mythical past in which the Founding Fathers were Christians all. They are also “victims” of a Leftist war on what the Founders stood for and, by extension, they represent. To win back America, as it were, Christo-authoritarians turn to less than democratic tactics, cozying up to authoritarians like Hungarian leader Victor Orbán and promoting a version of American history that is rooted in falsehoods. The goal is, of course, power and the suppression of civil rights for those with whom they disagree.

To round out the volume, ch. 7 functions as a primer in how to resist Christo-authoritarianism. Far from adhering to “objective” morality, Coley makes the case that white evangelicals often subjugate their moral bearings to the whims of their own socio-economic and political interests. This is particularly acute in their interpretation of the Bible, wherein the question “Whose hermeneutic do we trust?” is, our author contends, “roughly, ‘We’ll trust whoever uses Scripture to legitimize social arrangements that make American great for me.’ That’s moral relativism – and a particularly vicious form of relativism at that, since it pegs moral truth to the arbitrary preferences of those who enjoy privileged status within the established order” (pp. 198-199). Our author argues for moral realism, one in which people are paramount. Appealing to the Hebrew Bible and its emphasis on social justice, he decries the injustice he sees in evangelicalism: “[W]e dishonor our calling and misrepresent Christ to the world when we advocate for political institutions that serve the interests of wealth and power at the expense of the poor, and then dispense charity as though it were a substitute for justice” (p. 209). The antidote to Christo-authoritarianism, then, is to abandon promotion of one’s own interests and instead seek justice for all, especially the weak and marginalized.

On the heels of ch. 7 readers will find acknowledgements (including hilarious remarks about the author’s choice of attending Liberty University, a backhanded compliment he received from his thesis advisor, and more), the endnotes for the entirety of the volume, a bibliography, and an index.

REACTION

While much of what Coley has to say in Ministers of Propaganda rings true and is well-supported, there are nevertheless sections which to my mind seemed lackluster. Without getting into too much detail, his argument that the days of Genesis 1 cannot be literal, twenty-four hour days (as young earth creationists contend) lacks any exegetical rigor and seemingly depends on understanding the text through the lens of modern science rather than understanding the text as an example of ancient Near Eastern mythology.1 Additionally, his case that Genesis 2 is a “detailed rendering of specific, localized events that unfold during or after day six in Genesis 1” (p. 94) is problematic for a number of reasons, including that animal life in Genesis 1 is created prior to the creation of humans but in Genesis 2 the man is created (v. 7), then animal life (v. 19), and, finally, the woman (v. 21-22).2

These issues notwithstanding, Coley’s work generally offers a cogent and persuasive examination of the problematic ideals of the religious right, including the inconsistency with which they hold to some of their views. For example, in arguing for gender hierarchy, some evangelical leaders employ various prooftexts to demonstrate that their view is the “biblical” one. They utilize the propagandistic claims that egalitarian interpretations subvert the Bible’s authority as well as its perspicuity. But our author notes that this method of prooftexting and appeal to the aforementioned propaganda can be put to use in defense of legitimizing slavery. While relatively few evangelicals are keen to defend slavery, some leaders in the movement have bitten the bullet (so to speak) and offer various apologetics to defend it. Coley quotes at length men like John MacArthur, Albert Mohler, and Doug Wilson, so-called “thought-leaders” who have become household names in many a Christian home. Wilson, for instance, asserts that Northern abolitionists, driven by a hatred of the Bible, drove the nation to war against a South that was, by and large, filled with fine, Christian men and women whose ownership of other human beings was justified by Holy Writ.

The inanity on full display in the writings of Wilson and other like-minded evangelicals should engender not complacency but caution. Among many an evangelical there is a tendency toward Christian Nationalism, a movement that seeks to turn the United States into a kind of theocratic state wherein a privileged few exercise power over anyone who is not like them. “A nationalist,” observes historian Timothy Snyder, “encourages us to be our worst, and then tells us that we are the best.”3 Christian Nationalism does this under the guise of Christianity and conservatism, employing dog whistles and stereotypes to cast people of color as the enemy and “law and order” as the means by which the nation can be restored. That, of course, is nothing new. In her Pulitzer Prize winning biography of J. Edgar Hoover, Beverly Gage notes how Hoover “presented criminal activity first and foremost as a test of character,” and that it was a lack of discipline in the home that had created a perceived rise in criminal behavior.4 As a young boy, Hoover had become attached to a version of Christianity, proffered by his brother Dick, that decried the feminization of churches and advocated for a musclebound and anything-but-meek version of Jesus of Nazareth.5 And like his brother, Hoover attended George Washington University where, in his freshman year, he joined Kappa Alpha, a fraternity founded in 1865 to honor Robert E. Lee and, writes Gage, “actively promoted the Lost Cause myth, in which a noble South had been defeated by Yankee interlopers and Black agitators who misunderstood its way of life.”6 I fear the influence men like Douglas Wilson and John MacArthur may have on a future Hoover.

One of the many lessons one may learn from Ministers of Propaganda is that our democracy balances on a knife’s edge. So many on the religious right fain interest in democracy while actively promoting policies put to use by authoritarians. As white evangelicalism wanes, many in that movement have sought out political allies that can restore them to cultural power, even if that means utilizing anti-democratic ideas and policies. That evangelicals have cozied up to Donald Trump, for example, is evidence for this. Coley notes that the religious right appeals to a mythic past, rooted squarely in lies and polemic, to advocate for a “Christian” America. Treating the writings of the Founding Fathers as they do Holy Writ, evangelicals pick and choose what they find to promote a view of America’s history that is patently false. “In other words,” Coley writes, “conservatives reject the consensus of professional historians not because they prefer one version of American history over another but because they prefer mythology over history” (p. 188). The mythology proves to be a powerful basis upon which evangelicals build a vision for America that is not only anti-democratic but, in so many ways, is contrary to the vision of the nation’s founders.

CONCLUSION

All-in-all, Ministers of Propaganda proves to be as challenging a read as it is enlightening. More conservative readers will no doubt find fault with its portrayal of prominent evangelicals, but they will be mostly kicking against the goads. Coley has done his homework, offering citation after citation in addition to a very helpful bibliography. Additionally, his writing is compelling and he does a good job of laying out the logic of his arguments so that even a mere amateur like myself can follow along. Socially-minded Christians will find ch. 7 very useful as they think about ways to combat the rising tide of right-wing Christo-authoritarianism. Fundamentally, however, Ministers of Propaganda appeals to all those who loathe the hatred and bigotry of the religious right and seek to leave behind for their descendants a more just and loving world.

- For example, Coley notes that in Genesis 1 the sun isn’t created until day four (Genesis 1:14-19). But a “day” is ordinarily defined in relation to the sun and he “can’t conceive of what a day would be, if not a complete rotation of the earth relative to the sun” (p. 89, author’s emphasis). Thus, the days of Genesis 1 must not be literal, twenty-four hour days. Yet this ignores what is clear from the narrative: light exists independently of heavenly light sources like the sun, moon, or stars. In the worldview of the author of Genesis 1, light (Hebrew, ôr) is not tethered to light-governing entities like the sun or moon. This understanding of the natural world was not unique to the author as it is reflected not only among other biblical authors (e.g., Job 38:19-20; Isaiah 30:26) but also other ancient cultures. Mark Smith (The Priestly Vision of Genesis 1 [Fortress Press, 2010], 78) observes that in Enuma Elish, the Babylonian creation epic, the god Marduk is referred to as one appearing in “theophanic light,” dubbed “the sunlight of the gods” (Enuma Elish, tablet 1, line 102). This association with light is striking because, in the epic, Marduk has yet to create the cosmos, including the places where the heavenly bodies (e.g., sun, moon, etc.), associated with lesser deities, will reside. Smith writes, “The descriptions of Marduk represent the god’s divine light before and at creation. This fits with the presentation of the divine, preexistent line not only in Psalm 104, but also in Genesis 1:3, as I am proposing” (p. 78). See also Nahum Sarna, Genesis, The JPS Torah Commentary (The Jewish Publication Society, 1989), 7; Steven DiMattei, Genesis 1 and the Creationism Debate: Being Honest to the Text, Its Author, and His Beliefs (Wipf & Stock, 2016), 19.

Additionally, when Yahweh gives to Israel his commandments, the logic that stands behind the prohibition against working on the sabbath is that “in six days the LORD made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but rested the seventh day; therefore the LORD blessed the Sabbath day and consecrated it” (Exodus 20:11). For this line of reasoning to work, the days must be literal, twenty-four hour days. Cf. Deuteronomy 5:15. ↩︎ - For a comprehensive look at why many scholars believe Genesis 1 and 2 represent two distinct creation accounts, see DiMattei, Genesis 1 and the Creationism Debate, 1-63. ↩︎

- Timothy Snyder, On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century (Crown, 2017), 113. ↩︎

- Beverly Gage, G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Penguin Books, 2022), 196. ↩︎

- Gage, G-Man, 24-25. ↩︎

- Gage, G-Man, 38. ↩︎