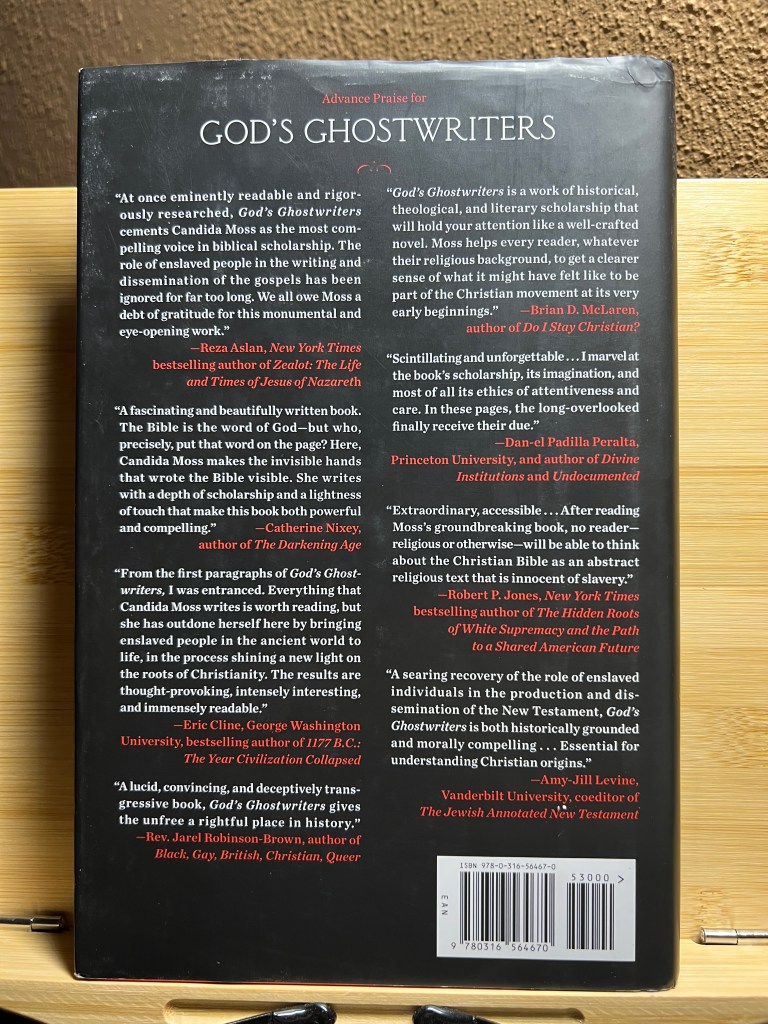

Candida Moss. God’s Ghostwriters: Enslaved Christians and the Making of the Bible. Little, Brown and Company, 2024. Pp. xi + 325. Hardcover. $30.00. ISBN 9780316564670.

INTRODUCTION

When thinking about the formation of the New Testament, what names typically come to mind? If you’re like me, you think of the apostle Paul, the Evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, and more. Perhaps you even think of names like Ireneaus or Athanasius since they are voices often associated with the form that the New Testament would take. These prominent persons obscure the reality of writing, editing, and publication in Greco-Roman antiquity. So often, enslaved people were part and parcel of the process and yet their names are so often lost to history. In Candida Moss’s latest book, God’s Ghostwriters: Enslaved Christians and the Making of the Bible, we learn how the enslaved put their stamp on the biblical texts as we have them today.

SUMMARY

Prefacing God’s Ghostwriters is a note from the author that lays out the difficulty with which writing about enslaved people entails. “The archives of history preserve fragmentary glimpses of the lives of enslaved people who lived in the ancient Roman world,” she observes (p. 3). To reconstruct their lives and the impact they had often requires historical imagination. It also requires moral fortitude since slavery in all its forms was an abhorrent institution. Wisely, Moss opines that “disinterested history is sometimes also morally negligent” (p. 7).

In the volume’s introduction, our author begins with an oft-overlooked fact about Paul’s letter to the Romans: he did not write it. At the close of the letter, we discover the epistle’s writer: “I Tertius, the writer of this letter, greet you in the Lord” (Romans 16:22, NRSVue). Tertius functioned as the apostle’s scribe, but given what we know about scribes in antiquity, he was almost certainly an enslaved person – an individual whose talent, training, and time was stolen and put to use by others for their own ends. And as slavery was ubiquitous in the ancient world generally and the Roman Empire particularly, they could be credited with any number of tasks that included reading, writing, editing and more. Thus, despite their marginalization, “enslaved people are as central to the history of ideas as they are to the history of labor” (p. 14).

The first chapter of God’s Ghostwriters opens the first major section of the volume (“Invisible Hands”) and begins with the story of an ancient graffito: a crucified man with the head of a donkey suspended near a young man named Alexamenos and accompanied by the caption “Alexamenos worships [his] god.” As Moss notes, this is probably an indication that Alexamenos was a Christian. But Alexamenos was also an enslaved person, working in the imperial household and training to become a copyist or secretary or some other related task. Were he trafficked due to war, he would have undergone humiliating inspections that would have invariably highlighted his otherness. Our author, however, thinks it more likely Alexamenos was a home-born slave, one who was trained from youth for a task he was destined to perform. Moss also explains that no matter how valuable their skillset or how educated they had to be (and, indeed, were even in comparison to their free counterparts), enslaved persons lived on the precipice of danger – physical, emotional, and sexual.

In ch. 2, Moss turns her attention to the apostle Paul, the star of not only the Acts of the Apostles but the New Testament generally. Paul would have been no stranger to slavery given its ubiquity in the ancient world, and, as our author notes, he may have been more intimately familiar with enslaved people than we might know. Not only was the early Christian movement likely filled with enslaved people and other persons of lower status, Paul himself was more than willing “to take advantage of the skills of servile workers,” including Onesimus, a slave of a Christ-follower named Philemon, whose work was so invaluable to the apostle that he begged his owner to send him back (p. 58). Following the Jewish War, undoubtedly many of those enslaved Jews were Christ-followers, and among them may have been the author of the Markan Gospel, a text written by one described by Papias as a veritable servile worker. And lest we think being enslaved meant one was less than intelligent, Moss discusses at length the use of shorthand as well as the ways in which Paul’s secretaries, in all likelihood enslaved persons, made known their presence in subtle ways.

The third chapter of our author’s work is a “rereading” of the story of Jesus as it is offered to us in the canonical Gospels, particularly the Gospel of Mark. She begins with the story of the paralyzed man in Mark 2, noting how the four individuals who bore the man to Jesus were likely enslaved and that Jesus’s focus on their faith stands in contrast to his words about the forgiveness of sin to the paralyzed man. Jesus himself would have been read by many consumers of Mark as one perilously close to slavery: he lacked a patronym, he was a construction laborer and, therefore, among those with few legal rights, he made great use of stories in the form of parables, he lacked the knowledge about when the “master” would come the way enslaved overseers typically did, and, poignantly, he dies a humiliating death feared by the enslaved – crucifixion.

Chapter 4 opens with the Acts of Thomas, a non-canonical story in which the disciple Thomas travels to India but does so as one trafficked. “I have a slave who is a carpenter,” Jesus tells a merchant by the name of Abban, “and I wish to sell him.”1 Thomas, purchased with silver coins, is then taken to India where he spreads the good news. This portrait of Thomas, our author goes on to observe, is in keeping with imagery of the ways in which servile workers functioned as messengers in antiquity. Often facing perilous circumstances to do the bidding of their enslavers, they carried abroad a variety of messages and media, including letters and books. In fact, enslaved messengers might function as readers and interpreters of their enslavers words, performing as if they were them so that the message sent was not received poorly. “They conjured the presence of the author with their voices, expressions, and hand gestures,” Moss writes (p. 130). Enslaved and otherwise lower-class Christ-followers were a fundamental reason that the message about Jesus spread as it did and, as our author points out, it became the focal point of pagan criticism of the movement. Nevertheless, Christianity “was, in ancient parlance, the unauthorized gossip of the masses, of women, and of enslaved people” (p. 138), a fact that undoubtedly contributed to its success.

In ch. 5, our author surveys curators of texts, often enslaved persons: “[W]herever you find repetitious work, you find enslaved and formerly enslaved workers” (p. 146). These servile individuals were critical in many stages of book production, including copying which involved not only correcting mistakes from a manuscript but, to a real degree, the creation of new understandings of a text thanks to a manuscripts ambiguity. One example she proffers is that of the epistle of 2 Corinthians, widely regarded as a composite text of many letters. Its existence is a testament to the creativity of its makers who, Moss notes, were likely enslaved. She also points out that the work of curating a text for the public was done by these men and women away from the public’s eye and that, she writes, “made their work inherently suspicious” (p. 166). Such was the prejudices against them. But their work is ultimately how we have so many ancient texts, the New Testament included.

That enslaved persons became the “faces” of the Gospels is the subject of ch. 6. “At gatherings of Christians it was the servile reader who brought the gospel alive,” writes Moss (p. 179). Just as performances of Gospel material today involve hand gestures and facial expressions, so too in antiquity would readers make use of their bodies to express and interpret the text they were reading. I say “interpret” because this is not simply what reading is but it was undoubtedly what performance must be. Our author offers the example of the centurion’s statement at the crucifixion that “truly this man was Son of God” (Mark 15:39). Depending on how the lector read this text, the centurion could be offering an honest appraisal of Jesus or perhaps a sarcastic one. Interestingly, Moss posits that readers would in a real sense become authors precisely because they became “the faces of the Gospel” (p. 193). As veritable stand-ins for the text’s “original” authors, these often-enslaved performers embodied the authority that stood behind the texts. A member of the audience likely would not have known “Mark” or “Matthew.” But they likely did know the person standing in front of them reading and acting out the Gospel of Mark or the Gospel of Matthew.

Chapter 7 begins with Blandina, an enslaved Christian who was regularly mistreated and eventually killed for her faith. “She whom society had deemed worthless,” writes Moss, “was now a model for others” (p. 204). What is interesting about Blandina is the way in which she is depicted as one filled with the power of God, inhabited by Christ as it were. Our author notes that in antiquity bodies were porous, susceptible to supernatural beings who could harm them or endow them with power. This was especially true of women and the enslaved. Moss also discusses slave language used throughout the New Testament. Various NT writers dubbed themselves douloi, though this was little more than metaphor. The apostle Paul, for example, refers to himself as Christ’s slave in his letter to the Romans (1:1) and even tells his Corinthian audience that they were “bought with a price” (1 Corinthians 6:20) just like the enslaved. But Paul was never enslaved and was instead, through his writings, “indulging in hyperbolic dress-up” (p. 230). In fact, for many readers of Paul down through the ages, his writings seem more pro-slavery than not such that his work was used to justify slavery in some of its worst forms, especially in the antebellum American South.

In the final chapter, ch. 8, Moss covers the morally fraught subject of punishment. The enslaved were often the recipients of horrible retribution for wrong doing, as illustrated by the story of Euclia, an enslaved woman from the Acts of Andrew. Though likely fictitious, the tale offers a glimpse not only into the inequity of Roman “justice” but also the coupling of disobedient willfulness and punishment that is part and parcel of many forms of Christianity. Our author highlights the “nightmarish” nature of incarceration with its dimly lit cells, putrid smells, and general grotesque conditions, and how these spaces became inspiration for many visions of hell. “These stories might be nightmarish,” writes Moss, “but they worked precisely because they drew from the conditions of real-world captivity” (p. 243). Hell as punishment works, she goes on to observe, precisely because it employs the logic of Roman slavery and a theory of justice that is entirely punitive. Those most vulnerable to the hell of a Roman prison were the poor and enslaved.

To close the volume is first an epilogue that summarizes God’s Ghostwriters by noting not only how enslaved collaborators are erased when we define authorship in too narrow a way or, because of some theological commitments, decide that they do not warrant acknowledgement but also points to the myriad interpretive difficulties such collaborators solve. Following this are various acknowledgements Moss makes to all those who helped bring this book to life, including very touching remarks about her parents (including her late mother) and her husband. Finally, the work ends with a note on abbreviations and translations used, copious end notes, credits, a list of illustrations, and an index. I should also note that readers can find more in-depth notes (and more) online at the book’s website, https://candidamoss.com/gods-ghostwriters.

REACTION

The existence of slavery in Greco-Roman antiquity is easy to take for granted, in large part because of how little it is discussed. During my evangelical days, I can count on one hand the times it came up in sermons, Sunday School, small groups, or conferences. And yet, as Moss shows, the language of enslavement is all over the New Testament. The problem, of course, is how translators handle that language, often rendering one of the primary terms for an enslaved person, doulos, as “servant” rather than “slave.” In the modern era, one hires a servant; slavery, on the other hand, is a thing of the past.

God’s Ghostwriters puts slavery front and center, and often in unexpected ways. For example, when Papias refers to Mark as Peter’s ἑρμηνευτής2 (hermēneutēs) there is likely more going on there than meets the twenty-first century eye. The term has its root in the world of communication and the related term ἑρμηνεύς (hermēneus) can refer to translators, expositors, or spokespersons.3 While such a superficial word study may tell us what the term means, it does not supply us with who fulfilled such tasks. “A great deal of ancient translation work was performed by enslaved people whose linguistic skills made them assets, but whose social status meant that their identities and their work are generally omitted from our historical records,” Moss writes (p. 66). The casting of Mark as a ἑρμηνευτής, our author goes on to note, purchased for Papias two things: an explanation for Mark’s lack of order4 and a defense of the Gospel’s integrity.5

That the accuracy of Mark’s writing is reflected by his apparent status as an enslaved person seems at first glance paradoxical. Given the status of enslaved people, wouldn’t it rather be the case that they were unreliable? But Moss notes elsewhere in God’s Ghostwriters that enslaved persons were often likely “the most educated men in the room” (p. 40) and were called upon by their enslavers to perform tasks that the enslavers themselves were either unwilling or unable to do. She offers the example of Calvisius Sabinus, a wealthy Roman consul, who could not remember the names of various heroes from the Trojan war and, per our author, “relied so completely on enslaved workers that he had some trained to memorize poetry for him. They would sit at the foot of his couch at social events and whisper quotations in his ear, only for Calvisius to butcher the poetic morsels in repetition” (p. 48). Calvisius’s use of enslaved workers was something of a faux pas because, as our author notes, while “wealthy Romans often used an enslaved nomenclator to recall people’s names and to memorize whole texts for performance, Calvisius’s failed attempts at erudition crossed a line” (p. 49).

Another unexpected example comes from the social situation of the apostle Paul and his letters. That Paul used secretaries for some (if not all) of his letters is beyond dispute. One such secretary makes himself known at the end of the letter to the Romans: “I Tertius, the writer of this letter, greet you in the Lord” (Romans 16:22, NRSVue). This seemingly mundane interjection has implications for slavery and the writing of what would become the New Testament. Noting how the language of “scribe” or “associate,” often used to describe Tertius’s role,6 effectively erases his social status, Moss writes that he was likely “one of the tens of thousands of erudite enslaved people who acted as stenographers, transcribed ideas, and edited the documentary output of the Roman world” (p. 11).

This may all seem quite trivial, especially from the perspective of a white, cisgendered, heterosexual male living comfortably in the American South. What Moss does well is to put into perspective not simply the roles enslaved persons played but, more importantly, the risks associated with their precarious positions. This often began with human traffickers whose strategies to make slaves appear younger and healthier resulted in invasive exams that saw them “stripped naked and publicly inspected: eyes were poked, limbs raised and lowered, orifices probed and fumigated, breasts and abdomens palpated” (p. 23). Young enslaved boys could become the victims of sexual assault at the hands of their enslavers if viewed as attractive. Our author writes that some of these enslaved boys were castrated to preserve their youthful visage, though some hoped to avoid such a fate by using concoctions that purportedly slowed down puberty. “They didn’t work,” Moss writes (p. 28).

If that made you uncomfortable, then good. It made me uncomfortable too. Because of what many of us were fed in evangelical apologetics, we are lulled into thinking that, in comparison to slavery in the Antebellum South, slavery in the Greco-Roman world was more akin to indentured servitude than chattel slavery.7 Apologists peddling such falsehoods do so because they have a vested interest in making Christianity appear to be beyond reproach. That they do so at the expense of truth is either lost on them either due to ignorance or to maintain status. Apologetics is one of the reasons academic study of the Bible – its text, paratexts, and contexts – is so important. Scholars like Moss provide crucial background that colors the black and white pages of the Bible, providing animation and illumination.8

CONCLUSION

Some readers of God’s Ghostwriters may be put off by the frequency of words like “probably” or “likely” that appear in the volume. But these terms do not suggest that Moss is guessing or is inventing history. Perusing the volume’s endnotes (as well as the extended notes at her website) reveals a scholar who has read deeply on the subject, indebted to many scholars who have thought about these issues before her. On display, then, is her own humility as she acknowledges that all historical reconstructions involve a measure of imagination that is tempered by the evidence. Indeed, she invites her readers “to check my impulses” (p. 5). This is the reason God’s Ghostwriters is such a valuable text. It is not simply that it is good scholarship but that it is good scholarship put to good use: giving a voice to the voiceless.

- Acts of Thomas 2. Translation taken from The Apocryphal New Testament: A Collection of Apocryphal Christian Literature in an English Translation based on M.R. James, edited by J.K. Elliott (Oxford University Press, 1993). ↩︎

- Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 3.39.15. ↩︎

- See The Cambridge Greek Lexicon, s.v. “ἑρμηνεύς” ↩︎

- Papias describes Mark’s Gospel as lacking τάξις (taxis), a term that typically refers to order or arrangement. Cf. The Cambridge Greek Lexicon, s.v. “τάξις.” There is, however, some debate on the usage of the term in Papias’s words. For a discussion, see Michael J. Kok, The Gospel on the Margins: The Reception of Mark in the Second Century (Fortress Press, 2015), 186-199. ↩︎

- See also Candida Moss, “Fashioning Mark: Early Christian Discussions about the Scribe and Status of the Second Gospel,” New Testament Studies 67 (2021), 193-195. ↩︎

- Commentators often note Tertius’s role as a scribe but either downplay the significance of it or otherwise fail to note Tertius’s social status. For example, Joseph Fitzmyer (Romans: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, The Anchor Bible 33 [Double Day, 1993], 749) writes that Tertius was “Paul’s Christian scribe” and that he was “adding these few verses in his own name.” Fitzmyer does acknowledge Tertius’s role in penning “the text of Romans” (p. 41) but beyond that says little. Similarly, James Dunn (Romans 9-16, Word Biblical Commentary 38B [Thomas Nelson, 1988], 909-910) notes that the name Tertius was “quite common among slaves and freedmen” (p. 909) but neither understands him as such nor believes that he did anything but compose the letter via dictation.

By contrast, in her recent commentary on Romans, Beverly Roberts Gaventa (Romans: A Commentary, The New Testament Library [Westminster John Knox Press, 2024], 442-443) posits that Tertius “may be an enslaved member of Phoebe’s household.” Similarly, Robert Jewett (Romans: A Commentary, Hermeneia [Fortress Press, 2006], 978-980) notes that amanuenses were often enslaved and offers up the view that Tertius was possible connected to Phoebe, in which case “a status of slave or freedman is likely” (p. 979) ↩︎ - E.g., J. Warner Wallace, “Four Differences Between New Testament Servitude and New World Slavery” (11.4.22), coldcasechristianity.com. Accessed 16 October 2024. As the title of the article suggests, Wallace doesn’t believe the “servitude” found in the New Testament compares to the slavery of the “New World” (i.e., the Antebellum period). It is therefore bewildering that he does not actually discuss any texts from the New Testament, preferring instead to present an array of verses from the Hebrew Bible that have no direct bearing on cases in the New Testament.

For an excellent response to evangelical apologetics on slavery, see Joshua Bowen, Did the Old Testament Endorse Slavery? second edition (Digital Hammurabi Press, 2023), 267-312. Bowen’s book is an excellent resource on slavery, particularly as it pertains to the Ancient Near East and the Hebrew Bible. I reviewed the first edition of the volume in 2020. ↩︎ - As James McGrath (The A to Z of the New Testament: Things Experts Know That Everyone Else Should Too [Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2023], 19) writes,

“Ancient authors and readers had shared knowledge and assumptions that facilitated communication between them. We lack those things and as a result misunderstand. This is one major reason why just reading the Bible and nothing else is simply not enough. Texts taken out of context become pretexts. That is true not only of small snippets quoted outside their original literary context but of whole books read detached from their historical and cultural context.” ↩︎

Fascinating. Great review. I will buy the book because of it. God’s grace in the midst of this and other unbearable subjects never ceases to amaze me, especially in light of Genesis 15:13. Blessings from the Lord to you

LikeLike