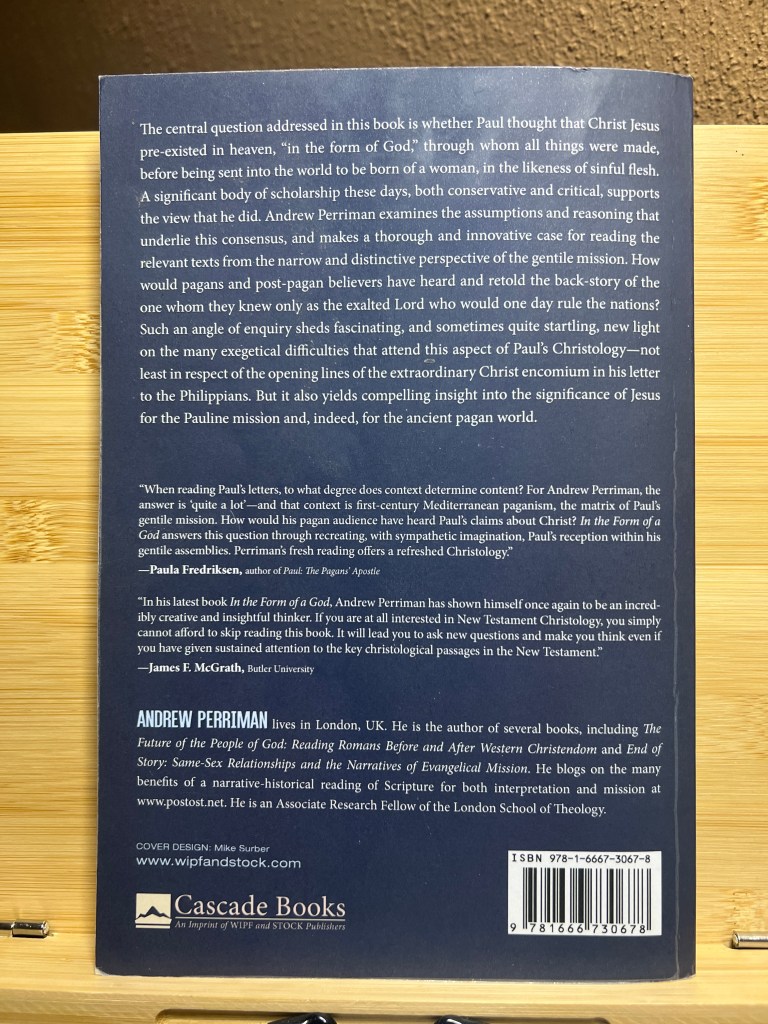

Author: Andrew Perriman

Title: In the Form of a God: The Pre-existence of the Exalted Christ in Paul

Publisher: Cascade Books

Year: 2022

Pages: 272

Price: $35.00 (paperback)

INTRODUCTION

The words of Paul in Philippians 2:5-11 have captured the attention of exegetes for nearly two millennia, rousing interpreters to formulate spirited defenses of Christ’s preexistence and deity as one who “was in the form of God” before “taking the form of a slave” (Philippians 2:6,7; NRSV). Though this understanding of Paul’s language is taken for granted as comporting to later orthodox and Trinitarian theology, it is not necessarily the best way to receive them as Andrew Perriman aptly demonstrates in his monograph In the Form of a God: The Pre-existence of the Exalted Christ in Paul (Cascade Books, 2022). In 272 pages, Perriman engages with myriad scholars who have sought to understand rightly the words of Paul in Philippians 2:5-11. More often than not, he finds reason to disagree with their interpretations, appealing to a range of sources both biblical and otherwise.

OVERVIEW

Chapter one introduces us to the central question of the volume: Did the apostle Paul think that Jesus was a divine, preexistent being? Perriman tackles not only the assumption that Paul and his audience shared such a Christology, but he attempts to root Pauline language – often taken to refer to heavenly preexistence – in historical events, noting that a specific future event – the Parousia – is for the apostle of primary importance. In ch. 2, our author examines the language of sending and its place in the conversation of Paul’s purported “high” Christology. Surveying instances in the LXX wherein someone or something is said to be sent, especially Moses and wisdom, Perriman concludes that God’s sending of Jesus in Pauline imagination “happens not in cosmic space and universal time but in Jewish space and historical time” (p. 36). Jesus is sent out the way Moses was sent out to rescue Israel from Egypt and not, as it were, as adivine figure from heaven. With ch. 3, our author turns his gaze towards a number of texts, primarily from the Corinthian correspondence. For example, 1 Corinthians 8:6 is taken by some interpreters as a not-so-subtle reference to the Shema with the result that Paul effectively includes Jesus in the divine idea. This Perriman roundly rejects. Other texts that can easily be taken to refer to divine preexistence followed by incarnational abasement – like 2 Corinthians 8:9 – are dealt with by Perriman in an arguably convincing manner.

Our author now begins in ch. 4 to deal with what is without a doubt the singular text that apparently advocates for divine, heavenly preexistence – Philippians 2:6-11. Specifically, he looks at the language of en morphē theou (“in the form of God” in most translations) and how the substantive morphē is used in ancient texts like the LXX, the works of Philo, the writings of Josephus, and more. Over and against exegetes who posit morphē refers to some invisible attribute of God or to his “glory” or even to the “image” of God, Perriman argues that the term refers to outward appearance. In ch. 5, he considers the idea that there is a conscious comparing and contrasting in Philippians 2 of Adam and Jesus (cf. Romans 5:12-21) such that Jesus is shown to be better than the progenitor of the human race by virtue of his not grasping for equality with God. Such an idea turns on morphē being synonymous with eikōn (“image”), a notion rejected outright by Perriman. Our author finds attempts to connect Jesus being en morphē theou to any figure that had heavenly preexistence to be without merit. Similarly, in ch. 6, Perriman turns away from so called “angelomorphic” understandings of the Philippian terminology. Did Jews think there would be an angel-like-messiah or an angel-like Son of Man? Perriman finds such ideas dubious.

Chapter seven signals something of a shift in the discussion with its title “Being in the Form of a God.” In it, Perriman looks at the appearances of deities from Greco-Roman sources and concludes that Paul’s morphē theou is decidedly “not a Jewish-Christian expression” (p. 135). Taking up the motif of the “divine man” in texts like the Gospel of Mark, our author opines that to a gentile audience the display of divine powers by Jesus would have been conceived of as the power of a god, situating Jesus in “a broad typology” that cut across various entities whether they be actual gods or superhuman beings. Consequently, Paul’s en morphē theou is better rendered “in the form of a god,” referring not to a pre-existent Jesus but to a pre-exalted one. In ch. 8, Perriman queries the meaning of the idea that Jesus “emptied” himself and did not “seize” equality with God. Interestingly, he posits that the point at which Jesus refused to seize that equality was the temptation in the wilderness, recorded in the Synoptic Gospels but never mentioned by Paul.

With ch. 9, the discussion turns to Colossians 1:15-20 with its language of Jesus being “the image of the invisible God” (v. 15) and the one through whom and for whom “all things were created” (v. 16). Such lofty language seemingly naturally lends itself to the interpretation of a preexistent divine Christ, but Perriman contends that this passage “describes the current post-resurrection status of the exalted Son, not a status acquired by descent from heaven and dwelling among people” (p. 195). Paul,[1] employing a wisdom motif, is not speaking of the cosmic order but of something more particular: the creation of a new world order by means of Jesus’s death and resurrection. This and more are reiterated in the volume’s conclusion wherein Perriman briefly summarizes the main points of the book.

ASSESSMENT

If there is but one word to use to describe Perriman’s volume it would be “impressive.” It is clear that he is well-read and at times I felt at a disadvantage because so many of the authors he wrestles with I have either never read or never heard of to begin with. While this is clearly a sign of my amateur status, it is nevertheless an opportunity for me to expand my knowledge. Perriman’s bibliography provides ample choices to that end and is a helpful guide in many ways.

But Perriman’s work is impressive in other ways. His reading of particular texts seems far more plausible than the “high” Christological/Trinitarian readings of many evangelical scholars. For example, commenting on Paul’s message to the Galatians that “God sent his Son, born of a woman, born under the law” (Galatians 4:4), William Hendriksen opines that “God’s Son existed already from eternity with the Father” and “the fact that he was now sent forth must mean that he now assumed the human nature…which was wondrously prepared in the womb of Mary by the Holy Spirit.”[2] But such commentary depends on categories of Christology with which the apostle Paul would not have been familiar. Far simpler and with better exegetical support is Perriman’s observation that “in the Greek Old Testament and literature of second temple Judaism when people are ‘sent out,’ it is to fulfill a task, and the emphasis, accordingly, is not on the place from which they are sent but on the place to which they are sent” (p. 20).[3] Thus, a divine, heavenly Christ need not be what Paul is referring to in Galatians 4. Indeed, as Perriman notes, Paul has already addressed the “from where” of Christ’s origin: he is the “seed of Abraham” (Galatians 3:19) and “not a heavenly figure” (p. 20).

Another example of Perriman’s more plausible exegesis of passages appears in his discussion of 2 Corinthians 8:9 – “For you know the generous act of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though he was rich, yet for your sakes he became poor, so that by his poverty you might become rich.” Writing about this passage, Ralph Martin asserted that the phrase “he became poor” is a reference to “[t]he incarnational event” and that “Paul wants to drive home the single point that the Lord of glory took the form of a human body.”[4] But Perriman isn’t convinced that this passage depicts a pre-incarnate Christ deciding to take on bodily form. He writes, “The construction in verse 9 does not suggest an exchange of mutually exclusive states, which is often implied in English translation: ‘he was rich…he became poor’ (ESV)” (p. 58). Noting a parallel construction in the story of Joseph and the wife of Potiphar from Josephus’s Antiquities[5] that he believes “effectively rules out any thought of incarnation” in v. 9, our author contends that what Paul means by Jesus becoming poor isn’t incarnation – from gloriously pure divinity to humanity – but “the acceptance of suffering and death” (pp. 58-59). And this just seems like a more straightforward reading of the passage, fitting well with what Paul says just a few chapters earlier that it was “[f]or our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Corinthians 5:21). Paul isn’t speaking of incarnation there. Why should he be doing so in 8:9?

I could certainly write more about all the places I found helpful and insightful in Perriman’s work, but I would be remiss if I didn’t point to a place where I’m skeptical of his interpretation. His exegesis of Philippians 2:6-11 is commendable in many ways, but in ch. 8 – “The Harpagmos Incident” – our author suggests that the language of v. 6, namely that Christ made no attempt to become God’s equal, refers “to the remembered incident when the opportunity to be equal to a god – perhaps even to the God of Israel – was put before Jesus by Satan” (p. 176). His defense of this view is intriguing and no doubt forceful. My difficulty with it is that the language Paul uses (or quotes) is too vague to say anything certain about its meaning. I think Perriman is right when he says that Paul has in mind a historical incident, but I am skeptical that we can say confidently that it was this or that specific historical incident. Perhaps it was during the Triumphal Entry that Jesus rejected the prospect of divine kingship (Mark 11)? Or maybe when he told Peter that he could have had legions of angels come rescue him (Matthew 26:53)? Many moments could be conjured up as candidates, but I don’t see any reason that any one of them are what Paul had in mind specifically. It’s not even clear to me that Paul knew of most of the events recorded in the Gospels at all. Perhaps he did, but we lack the evidential warrant to conclude confidently that he did.

CONCLUSION

The debate over Pauline Christology will never end and Perriman’s work is another volume among a seemingly infinite number discussing it. But I believe that In the Form of a God deserves serious attention from scholars and interested amateurs. For those of us who doubt Paul believed Jesus was a divine being or the second person of the Trinity, it is a helpful examination of texts traditionally used to defend such views. For Trinitarians, it is a challenge to the orthodox status quo that deserves to be addressed. I know Perriman’s work is one I will be recommending in conversations about what Paul thought about the incarnation and divinity of Jesus.

ENDNOTES

[1] Perriman accepts as a genuine Pauline writing the letter to the Colossians.

[2] William Hendriksen, Galatians, New Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 1968), 158.

[3] Though not strictly a text from the Second Temple period, in John 1:6 we are told that “[t]here was a man sent from God, whose name was John.” Surely this doesn’t mean John the Baptist existed in heaven before his birth or that he had some divine status. Rather, it points to a character who is sent by God for a specific task, namely “as a witness to testify to the light, so that all might believe through him” (v. 7).

[4] Ralph P. Martin, 2 Corinthians, Word Biblical Commentary Series (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1986), 263, 264.

[5] Cf. Antiquities 2.46.

Thanks for writing this. It makes me want to get the book and write my own review.

LikeLiked by 1 person