Author: Bart D. Ehrman

Title: Armageddon: What the Bible Really Says About the End

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Year: 2023

Page Count: 272 pages

Price: $27.99 (hardcover)

INTRODUCTION

When I was fourteen, our church’s youth group travelled to Rochester, NY to attend a “Youth Ablaze” rally. The featured preacher was the fiery Danny Castle who, with his Southern accent and rapid-fire delivery, delivered topical sermons that spent more time railing against the evils of modern culture (“Slips are for sluts,” “He was queer as a three-dollar bill,” and so on) than they did actually talking about biblical texts. As is common in these types of events, emotions ran high. It wasn’t simply that Castle was a powerful orator who could have convinced even Billy Graham he needed to repent and accept Jesus as his savior. Nor was it simply the desire for companionship – all those teenagers in the throes of puberty and hormones, looking for a community to belong to and an identity to which they could cling. A powerful element was the music. Two songs in particular stands out The first was “Hold the Fort,” a song written by the 19th century hymnist Philip Bliss. Perhaps some of my readers sang this song in their own churches.[1]

The other song is probably far less familiar to my readers. Not nearly as old as Bliss’s hymn, I first heard it at that rally. Here is one version of that song, entitled “I Shall Return.”

If you listened to the first verse, it is quite clearly alluding to the famous American general Douglas MacArthur. MacArthur, facing overwhelming Japanese forces encroaching upon where he was stationed in the Philippines, retreated to Australia. Here is how MacArthur biographer William Manchester explains the situation that led to the famous words “I shall return.”

Now it was Friday, and he was in the Adelaide station. Knowing that reporters would be there, asking for a statement, he had scrawled a few words on the back of an envelope: “The President of the United States ordered me to break through the Japanese lines…for the purpose, as I understand it, of organizing the American offensive against Japan, a primary object of which is the relief of the Philippines. I came through and I shall return.” He had worked and reworked the first sentence, which he hoped would lead the American people to demand, and the White House and the War Department to grant, a higher priority to this theater of operations. It was the last three words, however, which captured the public’s attention and became the most famous spoken during the war in the Pacific.[2]

Indeed, for it inspired the author of that fundamentalist song that I learned decades ago.

MacArthur’s “I shall return” and the New Testament’s expectation of the Second Coming fit like a hand in a glove. One text in particular fueled ideas about what that return and the end of the world would look like: the book of Revelation. There John the Revelator tells a story of how the once crucified and humiliated Jesus would return to trample his enemies, vindicate his followers, and set up his kingdom on earth. Many readers – including myself as a teenager and young adult – believed that this would happen very soon and the book of Revelation served as a kind of roadmap for what would happen in the near future. And while in my mid-20s I shifted away from the theological framework of what is known as dispensational premillennialism to Reformed amillennialism, this in no way dampened my hope for Jesus to come back. Though my understanding of the book of Revelation changed, I still prayed with John, “Come, Lord Jesus!” (Revelation 22:20)

Two terms in the paragraph above may have struck readers as strange: “dispensational premillennialism” and “amillennialism.” These terms refer to ways of interpreting language about the end of the world, including (and especially) the book of Revelation. The millennialism in their roots refers to the one-thousand-year reign of Christ spoken of in Revelation 20. These interpretive frameworks have their own offshoots and there is another form of millennialism known as postmillennialism. Christians disagree among themselves over which eschatological view is correct, and this is no doubt due to the fact that the book of Revelation – one of the main texts that speaks to eschatology – is itself a very weird and complicated book.

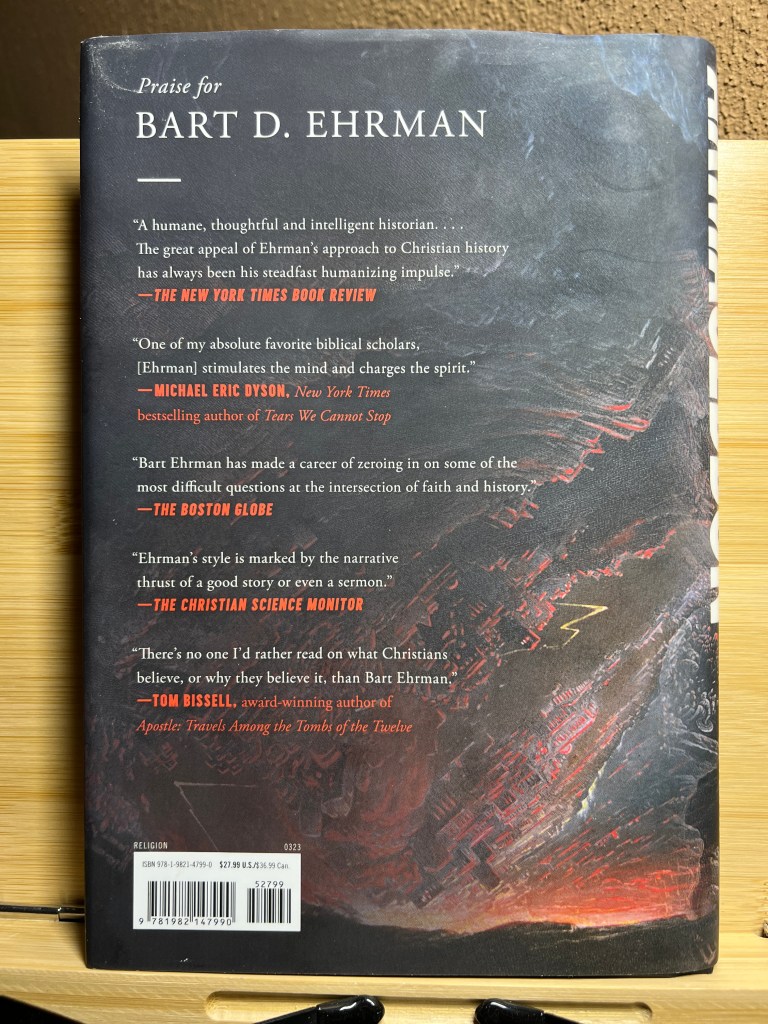

There are many commentaries and overviews on Revelation, some better than others. One of the more recent ones is Bart Ehrman’s Armageddon: What the Bible Really Says About the End (Simon & Schuster, 2023). In it Ehrman covers a range of topics that are connected in one way or another to the final book of the New Testament canon. From predictions about the end that failed to interpretive frameworks like dispensationalism to the contrast between the Jesus of Revelation and the Jesus of the Gospels, Ehrman’s Armageddon serves as an introduction to Revelation and what it has inspired.

SUMMARY

In ch. 1, Ehrman discusses the reception of apocalyptic and eschatological biblical texts among evangelicals like Edgar Whisenant, Hal Lindsey, and Tim LaHaye, as well as the difficulties with their approaches. Using the metaphor of a jigsaw puzzle, he notes that pulling a sentence here or a phrase there and from them building a coherent understanding of any text (let alone ancient ones) cannot result in a proper understanding of them. Given the importance of a book like Revelation, it behooves readers to try to understand it in both its literary and historical contexts – the project of Ehrman’s volume. It is to the book of Revelation Ehrman then turns in ch. 2, offering a section-by-section overview of the work. Having summarized the Apocalypse of John, in ch. 3 our author examines the various ways the book of Revelation has been read by Christians from the second century forward, including the rise of dispensational premillennialism and its proponents including C.I. Scofield with his Scofield Study Bible. Ehrman turns to “real-life consequences” of such apocalyptic beliefs in ch. 4, zeroing in on the Great Disappointment of 1843, the tragedy of the Koresh cult in Waco, TX, and the effect a particular reading of Revelation has had on environmental issues.

It is to the how of reading Revelation that is the subject of ch. 5. Our author not only defines and describes what an apocalyptic text is, but he offers readers a way to read specific passages in the book of Revelation with an appreciation for what apocalyptic brings by way of genre. Ch. 6 becomes an example of how not to read the book of Revelation. Ehrman expresses his skepticism about a non-violent reading of the book, noting the many ways that the purportedly gentle Lamb is a veneer for a harsh and wrathful God. And while the violence depicted in Revelation may be symbolic, as Ehrman rightly notes, it reveals the values of its author who can so readily depict his god in such terms. In ch. 7, our author compares the Jesus of the Gospels with the Jesus of Revelation. The contrast is sharp. The Jesus of the Gospels eschews wealth and demands his followers exhibit a life of service. The Jesus of Revelation, however, is the opposite: he is domineering and the reward for his people is wealth untold. This analysis comes to a head in the final chapter of the volume wherein Ehrman notes not only how the book of Revelation was and wasn’t received by the earliest Christians but also how the way in which we envision Jesus often informs our relationship with the world. If our Jesus is a servant of all, then we will be a servant of all. But if he is a conquering king with blood-soaked garments, then we run the risk of acting in similar ways. “Each of us has to decide,” Ehrman writes (p. 207).

ASSESSMENT

While there is much to be gleaned from Armageddon, I must confess that out of all the trade books I’ve read by Ehrman this one in particular has resulted in the smallest of personal harvests. This isn’t Ehrman’s fault, of course. He certainly didn’t write a book like this with me in mind. But when I compare Armageddon to his previous trade book Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020),[3] it feels at once like I’m reading two different scholars and (somehow) a carbon-copy. Not only is Armageddon considerably shorter than Heaven and Hell by eighty pages, one of the central chapters of the book, ch. 5’s “How to Read the Book of Revelation,” is functionally redundant if one already owns his The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings (Oxford University Press). Granted, that volume is a textbook, and the price tag is relatively high, but with it comes not only content on the book of Revelation but the entirety of the New Testament and other writings from the early Christ-following movement. You really get your money’s worth. The essential content of Heaven and Hell, however, cannot be found in Ehrman’s OUP textbook.[4] Moreover, the book of Revelation is the subject of ch. 11 of that volume and Ehrman goes into topics like the genre of apocalyptic, the various symbols found in Revelation, and more. In addition to all of this, there were moments in reading Armageddon that I became uninterested simply because of much of what was discussed could be found in any number of quality study Bibles like The HarperCollins Study Bible, The Jewish Annotated New Testament, or The New Oxford Annotated Bible. Obviously, Ehrman should not be expected to reinvent the wheel, and what he is doing more often than not is merely summarizing consensus scholarship. But for regular readers of Ehrman – those perhaps more likely to purchase his books – some of the material feels regurgitated.

Nevertheless, there are moments where Armageddon shines. Chapter four, “Real-Life Consequences of the Imminent Apocalypse,” resonates strongly with me because of how steeped I was in Young Earth, dispensational, King James Only fundamentalism as a teenager. As I mentioned in the introduction, the expectation of Jesus’s return in the immediate future was part and parcel of the fundamentalism I knew and loved. And it did precisely what Ehrman discusses in the chapter: it increased my desire to see Israel be restored to its full place in eschatological imagination (i.e., building the temple and thus giving opportunity for the Antichrist to make himself known) as well eliminated any concern for the environment, at least as it pertained to anthropogenic climate change. Time and again from the pulpit we were reminded, from the words of 2 Peter 3, that God would not flood the earth but would instead destroy it with fire. Even if the world was heating up, surely this just pointed to the nearness of the end.[5]

Violence Galore

My favorite chapters of this volume were its final three. Taken together, they provide a powerful argument that the Jesus of Revelation and the Jesus of the canonical Gospels are two entirely different entities. In ch. 6, Ehrman spends time looking at God’s wrath found in the Hebrew Bible. He prefaces the discussion by noting the way in which some people contrast the God of the New Testament with that of the Old. Some believers (and some atheists) are fond of laying out this distinction, but I stand with Ehrman when he writes, “I always wonder if these people have ever read the book of Revelation” (p. 144). In what follows, Ehrman examines God’s wrath as it appears in some very violent parts of the Bible, like the Pentateuch and the book of Joshua. In many a story, Yahweh is portrayed as a blood-thirsty, revenge-fueled god. One story that sticks out to me comes from 1 Samuel 15. There Yahweh sends Samuel to anoint Saul as king over Israel and to commission him to destroy the Amalekites because, the deity says through the prophet, of “what they did in opposing the Israelites when they came up out of Egypt” (v. 2). This is a call-back to Exodus 17 when the Amalekites attacked a vulnerable Israel at Rephidim. At the close of the battle, Israel was victorious, but Yahweh was not happy: “Then the LORD said to Moses, ‘Write this as a reminder in a book and recite in the hearing of Joshua: I will utterly blot out the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven’” (v. 14). In 1 Samuel 15, the deity plots and plans to revisit the Amalekites and “blot out the remembrance” of them by Saul’s hand. The new king is to “kill both man and woman, child and infant, ox and sheep, camel and donkey” (v. 3). So much for being “pro-life!”

Ehrman observes that God’s wrath is a recurring theme in many prophetic texts like Amos and Hosea. And while he expresses his general agreement with scholars who point out that being wrathful is not the dominant depiction of God in the Hebrew Bible, he points out that in many places “God’s love comes to very few” and that “he exacts this wrath in horrifying ways, inflicting terrible suffering and death on innocent boys, girls, and infants because of the sins of others” (p. 155). Though in many ways this isn’t the kind of deity to be found the Gospels, in the book of Revelation this version of God is front and center, giving his love to a select view while at the same time exacting horrible revenge upon the world. Contrary to those who would read Revelation non-violently,[6] Ehrman carefully documents how both God and Jesus act as violent agents.

One section that surprised me was Ehrman’s treatment of Revelation 18, a section on the fall of “Babylon,” i.e., Rome. As a regular reader of the Bible since I was 17, I have read the book of Revelation dozens of times. Despite my familiarity with Revelation, I managed to miss something that Ehrman so aptly illuminates. In v. 4, a voice from heaven says, “Come out of her, my people.” As you can tell even in English translation, the word translated “Come out” in the NRSV is a second-person plural verb in the imperative mood. It is addressed, no doubt, to Christ-followers living in Rome. They are to flee the city because Rome’s sins have piled so high that they have encroached upon heaven itself (v. 5). The imagery here is derived from the book of Jeremiah where Yahweh declares judgment on Babylon and says, “Flee from the midst of Babylon, save your lives each of you! Do not perish because of her guilt, for this is the time of the LORD’s vengeance; he is repaying her what is due” (Jeremiah 51:6).[7]

The angel’s words, addressed to Christ-followers in Rome, do not end there. In vv. 6-7 he continues: “Render to her as she herself has rendered, and repay her double for her deeds; mix a double draught for her in the cup she mixed. As she glorified herself and lived luxuriously, so give her a like measure of torment and grief.”[8] Readers more careful than I likely paid attention to the verbs “render,” “repay,” “mix,” and “give.” They are all in Greek second-person plural verbs in the imperative mood. To whom are these commands addressed? As Ehrman points out, it must be to the same group mentioned in v. 4 – Christ-followers! He writes, “These are the orders delivered to the followers of Jesus: Rome has made you suffer, so return the favor double. Torment and grieve the supporters of Rome twice as much as they tormented and grieved you” (p. 159).

For some readers this may be quite the surprise. It was for me. If we take as background for this passage the source that inspired it, it makes more sense. In Jeremiah 50, the prophet says that Yahweh “has opened his armory and brought out the weapons of his wrath” (v. 25). In v. 29, the command is given: “Summon archers against Babylon, all who bend the bow. Encamp all around her; let no one escape. Repay her according to her deeds; just as she has done, do to her – for she has arrogantly defied the LORD, the Holy One of Israel.” John the Revelator was clearly familiar with his prophetic predecessors. From violent rhetoric from the prophets of old against Babylon comes violent rhetoric against a new Babylon.

This divinely commanded violence is also not surprising in light of everything else we read in the book. Despite his description as a lamb, the Jesus of Revelation acts more like a conquering king. Ehrman notes that from the first chapter Jesus is depicted in cosmic terms as one from whose mouth “a sharp, two-edged sword” emerges. Even if this is a way of referring to the Word of God, “for John this Word is not a peaceful, soothing communication to calm the souls of those on earth” (p. 161). With it, Jesus makes war (Revelation 2:16; 19:13, 21) and war is never peaceful. As Ehrman shows, passages found in chs. 14 and 19 are illustrative of this violent tendency. Moreover, even if the imagery is symbolic, it does us no good because such symbolism “embody [John’s] understanding of God, the world, and humanity” (p. 166), offering us a glimpse of his “deepest values, commitments, perspectives, and beliefs. And John’s are deeply disturbing” (p. 167).

The Deceitfulness of Riches

The violence Jesus perpetrates in Revelation and the command that his followers should do the same to Rome is in many ways antithetical to the Jesus of the Gospels. “My kingdom is not from this world,” the Johannine Jesus told Pontius Pilate. “If my kingdom were from this world, my followers would be fighting to keep me from being handed over to the Jews. But as it is, my kingdom is not from here” (John 18:36). Even the Synoptic Jesus, as powerful as he is, does not seek retribution against those who nail him to the cross.

We can see the contrast between the Jesus of Revelation and the Jesus of the Gospels in another way: how descriptions of wealth and power are offered, the subject of ch. 7 of Armageddon. Ehrman writes, “For [John] there was no problem with wealth and power per se. The problem was that the wrong people had them” (p. 170). The Jesus of the Gospels had problems with both, commanding the rich to sell their possessions (Mark 10:23) and telling his disciples that they were to be like the Son of Man who “came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many” (Mark 10:45). But in the book of Revelation, the tables seem turned.

One of the many ways that this becomes abundantly clear is in the extravagance of the New Jerusalem (Revelation 21:9-27). A few chapters earlier, people on ships in the waters near Rome witness its destruction and ask, “What city was like the great city?” (Revelation 18:18)[9] The answer to that question comes in ch. 21. “The ground alone is covered by two million square miles of solid gold,” Ehrman writes. “It defies the imagination and is supposed to. The followers of Jesus will live in opulence beyond anyone’s dreams. By comparison, ancient Rome would look like a termite nest” (pp. 180-181; cf. Revelation 21:15-18). What city is like the New Jerusalem?

CONCLUSION

At the end of Armageddon, Ehrman challenges readers to choose between the Jesus of the Gospels and the Jesus of Revelation. He notes that for people who place a premium on imitating Jesus, the way in which we depict him matters. Because the book of Revelation offers a Jesus who is violent towards those with whom he disagrees, some people take this as license to act the same. The Apocalypse depicts a wrathful and domineering Jesus. “This is not the Jesus of the Gospels,” Ehrman writes,

but it is the wrathful Lamb of the Apocalypse. It is also the portrait of Christ many people prefer today. It is a portrait that enables and encourages Jesus’s followers to embrace violence, vengeance, domination, and exploitation, to do whatever it takes to assert their will to others. Some of these people have been our neighbors. Some of them have been our leaders. Some of them very much want to be our leaders.

What would the Jesus of the Gospels make of them? (p. 206)

This is perhaps the greatest contribution Armageddon makes to our contemporary circumstances. By illuminating the way in which Revelation depicts Jesus and juxtaposing it with the way in which the Gospels do, Ehrman forces us to think through the implications of each. One Jesus can turn us toward violence, obsessing over wealth and power. The other can turn us toward service, remembering that the Son of Man washed the feet of his disciples, rubbed elbows with society’s outcasts, and touched the sick. Which one do we choose?

“Each of us has to decide” (p. 207).

[1] Here is the opening verse and the refrain.

Ho, my comrades, see the signal, waving in the sky!

Reinforcements now appearing, victory is nigh.

“Hold the fort, for I am coming,” Jesus signals still;

Wave the answer back to heaven, “By Thy grace we will.”

This song had it all: the idea of a community (“Ho, my comrades”), a call to watchfulness (“see the signal”), the hope of an imminent return of Jesus (“Reinforcements now appearing, victory is nigh”), a call to stand firm in the faith (“Hold the fort, for I am coming”), and the relationship believers have with Jesus (“By Thy grace we will”). Bliss wrote many hymns and a good number of them had as their theme Jesus’s return. One of my favorite hymns remains one for which Bliss wrote the music, the lyrics having been composed by Horatio Spafford. It was titled “It Is Well with My Soul.” The final verse reads,

And Lord, haste the day when my faith shall be sight,

The clouds be rolled back as a scroll;

The trump shall resound, and the Lord shall descend,

Even so, it is well with my soul.

I can still here my father shout “Amen!” upon hearing these words during church service.

[2] William Manchester, American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880-1964 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1978), 270-271.

[3] See my review of Heaven and Hell.

[4] At least not in the edition I own, the sixth.

[5] I’m almost certain I heard this from the mouth of KJV Only evangelist Samuel Gipp on more than one occasion.

[6] Though I have not yet had an opportunity to read it, Scott McKnight has recently published a work on Revelation that seeks to understand it in non-violent terms. See McKnight, Revelation for the Rest of Us: A Prophetic Call to Follow Jesus as a Dissident Disciples (Zondervan, 2023).

[7] See David E. Aune, Revelation 17-22, Word Biblical Commentary 52c (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, Inc., 1998), 983.

[8] In his commentary on Revelation, Craig Koester writes,

By analogy, Babylon’s wine is the seductive quality of power, luxury, and violence, which the nations imbibe. When these forces lead to the destruction of those who consume them, they function as the wrath of God. The symmetry in judgment parodies the principle of generosity: If Babylon’s insatiable desires ruin the world, let her have all the ruination she wants (19:2) If the whore has an insatiable thirst for violence, let her drink the cup of violence filled twice over (17:6).

See Koester, Revelation: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, The Anchor Yale Bible 38a (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014) 716.

[9] Though an expression younger than the writing of Revelation, I think there is some irony in the maxim “Rome wasn’t built in a day” when set alongside Revelation 18:19: “And they threw dust on their heads, as they wept and mourned, crying out, ‘Alas, alas, the great city, where all who had ships at sea grew rich by her wealth! For in one hour she has been laid waste.” Rome may not have been built in a day but in the prophetic mind of John it is destroyed in less than one.