As a boy, I was obsessed with the TV show In Search Of. Hosted by Leonard Nimoy, the program was all about the weird and outlandish, and it came with the caveat that “this series presents information based in part on theory and conjecture.” In the span of about thirty minutes, Nimoy would over topics ranging from the disappearance of Amelia Earhart to Bigfoot to the Garden of Eden. One of the more memorable episodes was episode nineteen of season three – “Noah’s Flood.” There Nimoy covers not only the flood itself but also the ark built by Noah at the behest of God as well as the modern search for the vessel which, per the biblical story, “came to rest on the mountains of Ararat” (Genesis 8:4, NRSVue). In referring to the narrative found in the pages of the biblical book of Genesis, Nimoy calls it “the greatest legend of all,” an apt moniker considering how it has inspired artwork, films, literature, and the earnest search for its existence.

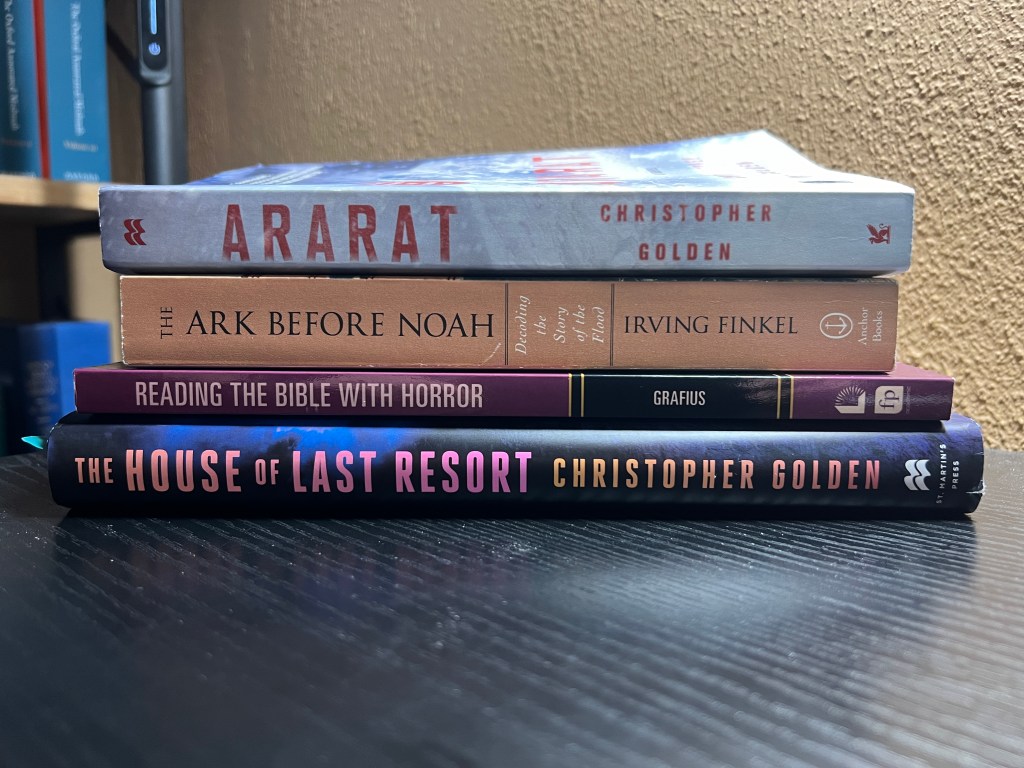

Noah’s ark has yet to be found, despite numerous searches over the last few centuries. But what would happen if it was? That’s the subject of novelist Christopher Golden’s 2017 book Ararat: A Novel (St. Martin’s Press). In it, a portentous earthquake reveals an opening in Mt. Ararat that turns out to be a boat uncannily similar to that of the biblical account. But inside the vessel lurks a malevolent force, released unintentionally by a group of researchers trying to get to the truth of what they have found. With the ark and the mountain serving as literal and figurative frameworks for much of the narrative, Golden manages to wed lore surrounding Noah’s ark with common horror themes, the end result being a novel that is as creepy as it is entertaining. It’s also, in its own way, a story about love and jealousy, about the dangers of secrecy, and, how even the best of us can fall prey to our worst inclinations.

The story’s central protagonist is Ben Walker, a man laden with guilt about his relationship with his young son and who, it is revealed, has seen some hairy stuff over the course of his career. He arrives on Ararat three weeks (and four chapters) after the thrill-seeking couple of Adam and Meryam have already made the trek up the mountain with about a dozen others, including a biblical scholar by the name of Armando Olivieri. The climb results in what one might expect from such an arduous undertaking: exhaustion. But it also hints at something more, with one character attributing to altitude sickness a secret she has been keeping from those she cares about.

As the ark takes center stage – “quiet and ancient and looming” – so too do the disturbing finds within it. While the researchers stubble upon animal stalls, consonant with the details from the biblical story, they also find far less comforting artifacts, chief among them a blackened coffin, covered in bitumen, and within it a corpse with demonic features. Walker, we find out, is interested chiefly in that coffin and has brought his own makeshift team to assess it, including Father Cornelius. The priest enjoys some measure of expertise in ancient languages and has come to aid in the translation of text written in a strange dialect on and in the coffin. But as soon as Walker arrives on the scene, trouble ensues. Fear strikes members of the team, people go missing, and a shadow lurks ever at the periphery.

While work continues in the ark, the temperature outside plummets even while tempers within flare. Adam and Meryam begin to feel alienated from one another, Olivieri and Father Cornelius battle over syntax, and debate over what to do with the cadaver rages. How much of this is the demon at work and how much of it is just human nature is left up to the reader. While much of the conflict can be attributed to people being people, the demon surely puts its stamp on the growing body count. The race begins to not only stop it from destroying them all but also to leave the ark even while a blizzard rages outside. Can they make it down intact? How many of them will fall?

Ararat is undoubtedly one of the most stressful horror novels I’ve read. Toward the end of the book, as the team descends the mountain and with them the malevolent spirit, I found myself reading as fast as I could hoping somehow that by rushing through page after page I would save the characters, my expeditious reading hurrying them along safely to the mountain’s base. With every turn of the page, my anxiety grew as I feared that lurking in the ensuing words would be the demon, working its evil to destroy Walker, Farther Cornelius, Adam, Meryam, and the rest. The core of the novel is a masterclass in how to write in a way that the reader feels acutely the anxiousness and anger experienced by the characters. (I think my shoulders are still sore from where I carried those unpleasant feelings.)

As someone whose main interests lie in biblical studies and ancient histories, most tantalizing about Ararat were the ways in which those fields intersect with horror in Golden’s novel. The most obvious example comes from the title of the book itself. Few readers in the West, I would venture to guess, could hear the word “Ararat” and not think of Noah’s ark. The mountain is a veritable metonym for the story from Genesis. Additionally, and despite the taming of the story of the Deluge in modern culture, Golden’s appropriation of Noachian imagery for the purposes of horror story telling is in keeping with the mood of Genesis 6-9. Indeed, the violence that permeates Ararat is of a kindred spirit (pun intended) to the violence of Genesis, both that which stirs regret in Yahweh (Genesis 6:5-7) and that which the deity pours upon the world of men itself.

It is not only the biblical text with which Golden is familiar and from which we he derives inspiration, but pseudepigraphic and rabbinic texts as well. For example, in ch. 14 Father Cornelius offers background to his translation of mysterious language that he had found in the coffin beneath the demonic corpse. “Most of what’s there – what was beneath the cadaver – is a history,” he tells Walker and the rest. He then brings up lore attendant to the Noachian narrative, including Genesis Rabbah (i.e., Bereshit Rabbah), a midrash of the book of Genesis from around the fourth century CE. The priest explains that in it, Noah purportedly brought demons with him on the ark and that around the time of Enos humanity went from being in the image of God to something less divine. All of this does indeed appear in Genesis Rabbah.1 Moreover, the name of the demon in Ararat, Shamdon, is taken from that midrash.2

In addition to pulling from the aforementioned texts, Golden has also taken as a source for his novel the work of Berossus, a Babylonian historian from the third century BCE. Again in ch. 14 of Ararat, Armando Olivieri, a biblical scholar part of the original research team, offers background on the bitumen found in the ark. In addition to the coffin being covered in bitumen, corpses near it donned necklaces of the material. Olivieri draws attention to this and tells the group that Berossus claimed to know people who “lived in the shadow of the mountain” and “wore shards of hardened bitumen on cords around their necks as wards against evil.” Though Berossus’s work is no longer extant, bits and pieces of it can be found in the writings of other historians, including the Jewish historian Josephus who quotes Berossus in his commentary on the flood story in his Jewish Antiquities:

This flood and the ark are mentioned by all who have written histories of the barbarians. Among these is Berosus the Chaldaean, who in his description of the events of the flood writes somewhere as follows: “It is said, moreover, that a portion of the vessel still survives in Armenia on the mountain of the Cordyaeans, and that persons carry off pieces of the bitumen, which they use as talismans.” (Jewish Antiquities 1.93)3

By incorporating these ancient accounts into his novel, Golden adds more weight to the horror within it. For me, it made the book even more compelling.

Though this is the first novel I’ve read by Christopher Golden, it will surely not be my last. Ararat has whet my appetite for more. The horror is palpable and the themes that undergird it – the dangers of secrecy and distrust, the role trauma plays in how we view the world, the vulnerability we experience in love and being loved – serve to heighten the fright fest in this diabolical tale. The only thing that would have made this better is if I had read it on a cold winter’s night with the wind beating against the windows of my home.

Did you hear that devilish laugh too?

- On Noah’s taking demons (disembodied spirits) upon the ark, see Bereshit Rabbah 31.13. On the nature of humanity until the time of Enos, see Bereshit Rabbah 24:6. ↩︎

- See Bereshit Rabbah 36:1. ↩︎

- Translation taken from Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, Books 1-3, translated by H. St. J. Thackeray, Loeb Classical Library 242 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1930). ↩︎

1 thought on “‘Ararat: A Novel’ by Christopher Golden – A Brief Review”