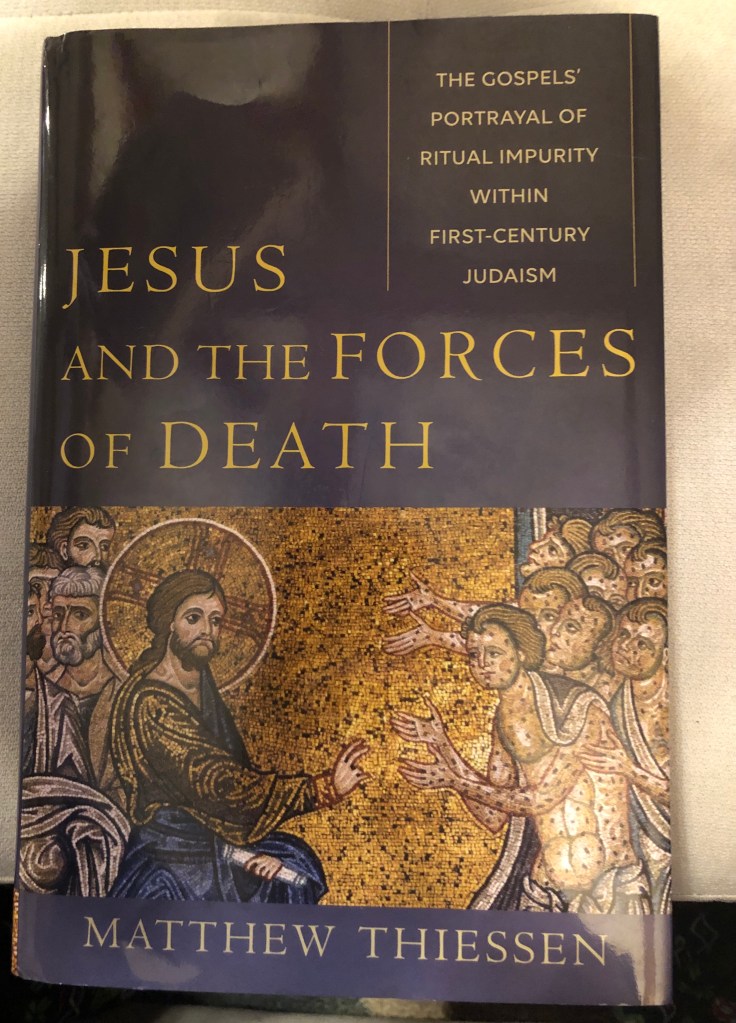

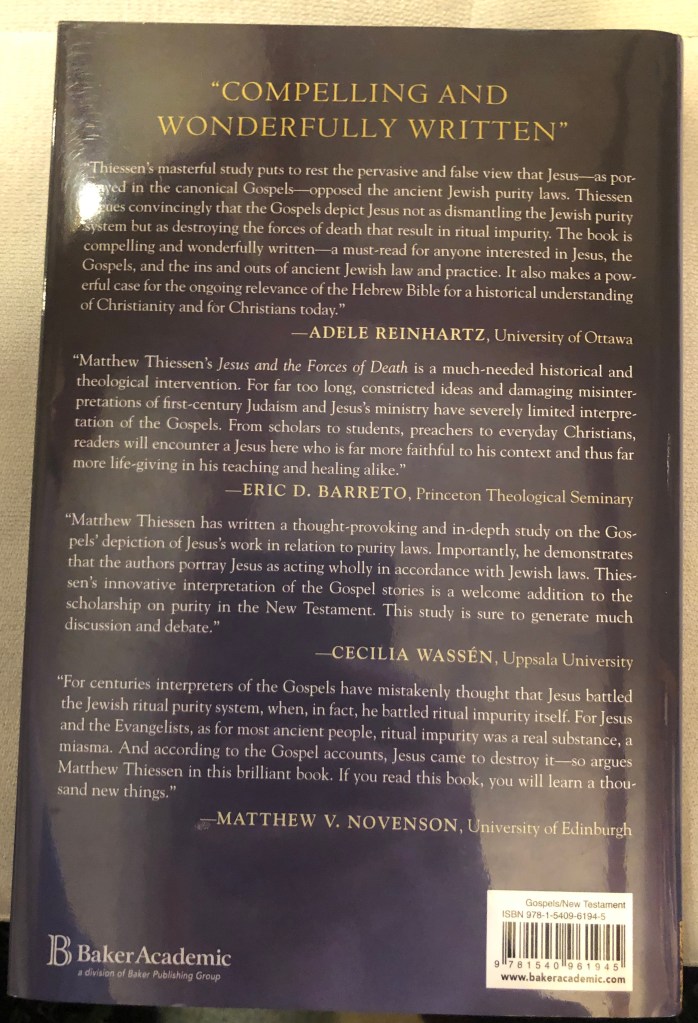

Author: Matthew Thiessen

Book: Jesus and the Forces of Death: The Gospels’ Portrayal of Ritual Impurity within First-Century Judaism

Publisher: Baker Academic

Year: 2020

Total Page Count: 256

Price: $39.99 (hardcover)

INTRODUCTION

In Mark 3, Jesus enters a trap disguised as a synagogue. There seated among the faithful Jews who had gathered that sabbath was a man with exērammenēn…tēn cheira, “a withered hand” (v. 1), probably a reference to some kind of physical paralysis and the atrophy it tends to bring.[1] Whether the man had come to be healed by Jesus isn’t stated but v. 2 reports that the Pharisees (cf. v. 6) see this as a fortuitous turn of events: “They watched [Jesus] to see whether he would cure him on the sabbath, so that [Greek, hina] they might accuse him.” They’ve got the bait and now they just wait to see if Jesus will spring the trap. But Jesus is setting up a trap of his own, telling the man to come to him (v. 3) and then asking the fundamental question, “Is it lawful to do good or to do harm on the sabbath, to save life or to kill?” There is no response; they all remain silent (v. 4). They have sprung his trap for, angered and grieved, Jesus uses this moment as an opportunity to answer his own question – it is lawful to do good even on the sabbath. He commands the man to stretch out his withered hand: “He stretched it out, and his hand was restored” (v. 5). Nevertheless, the Pharisees’ trap worked and they “went out and immediately conspired with the Herodians against him, how to destroy him” (v. 6).

Whence such controversy? Why would Jesus’ actions on the sabbath elicited such a response from the Pharisees? More importantly, what would the Markan audience who read or heard this series of events thought about it all? For some modern exegetes, stories like this one in Mark 3 are symptomatic of Jesus’ overall view of ritualistic laws. For example, evangelical scholar D.A. Carson, thinks that the earliest Christians viewed the sabbath as “shadow of the past” and would not have done so “unless they had grasped the significance of Jesus’ teaching in this connection.”[2]Thomas Schreiner reasons that Jesus’ choice to heal on the sabbath was intentional.

Jesus could have selected a different day to perform his healings and thus avoid controversy. By healing on the Sabbath, however, he indicated that the Sabbath must be interpreted as pointing to him and his work. The Sabbath must be interpreted eschatologically and christologically as well, for it too points to the final rest that the Lord will grant to his people.[3]

Later, Schreiner claims that Jesus’ apparent views on things like the sabbath, kosher regulations (e.g., Mark 7:19), and more signify that the

prescriptions of the OT law are not necessarily binding now that Jesus has arrived. They must be interpreted in light of his coming…. Mark does not work out in detail any view of the OT law, but we have some indications that the prescriptions of the OT are not necessarily binding upon Jesus’ disciples.[4]

But is this the best way to understand Jesus’ views on the Torah? Matthew Thiessen (PhD, Duke University) doesn’t think that it is. In his 2020 volume Jesus and the Forces of Death: The Gospels’ Portrayal of Ritual Impurity within First-Century Judaism,[5] he contends that “the Jesus that the Synoptic Gospel writers depict is a Jesus genuinely concerned with matters of law observance” (xii). Thiessen notes that while some scholars gladly situate Jesus in his Jewish context, they nevertheless think of him as being against certain elements beliefs and practices common among many first-century Jews. In other words, Jesus was a Jew but not thoroughly one. “One of my central aims in writing this book,” Thiessen counters, “is to show that the Gospel writers portray a Jesus who really was that Jewish” (p. 2).

Note: I will refer to Jesus and the Forces of Death as JFD throughout.

SUMMARY

Following a “clarification” (pp. xi-xii) in which he makes his readers aware that JFD is not about the historical Jesus but rather the canonical/literary one (pp. xi-xii), and laments how many commentators have routinely “misconstrued the Gospel writers’ portrayals” of Jesus, Jewish law, and the ritual purity system” (p. xii), Thiessen’s introduction (pp. 1-8) lays out the reason such a book as JFD is needed: “I am persuaded that we often misunderstand the Gospels writers’ depictions of Jesus because we naturally and unthinkingly transfer him and the people of the literary world of the Gospels into our own conceptual world” (p. 3). One main area of concern is cultural: most modern people do not have a ritual purity system like the one that existed in first-century Palestine and, so, cannot conceive of either its function or inner logic. Another is that because he is associated with Christianity, and Judaism has been construed as “sterile, heartless law observance” (p. 5), Jesus is thought of as one who laid out a new system of dealing with sin and God. This, Thiessen contends, is little more than “religious apologetics masquerading as historical research” (p. 5). He closes the introduction by writing, “The Jesus of the Gospels only makes sense in light of, in the context of, and in agreement with priestly concerns about purity and impurity documented in Leviticus and other Old Testament texts” (p. 8). What concerns were those?

That question is addressed in ch. 1, aptly title “Mapping Jesus’s World” (pp. 9-20). Reading any other chapter of JFD without first reading ch. 1 will only contribute to misunderstanding Thiessen’s views. In it, he lays out the distinction between holy/profane and pure/impure, consciously and carefully showing that to conflate holy with pure or profane with impure would be a mistake. “The category of holy pertains to that which is for special use – in this sense, related to Israel’s cult and therefore to Israel’s God,” he writes. “On the other hand, the category of the profane…refers to that which is secular or for common use” (p. 9). Everything in the world can be placed into either category. This is also the case for the categories of “pure” and “impure” – everything in the world fell into one of these two categories. An Israelite could be a combination of these categories: holy and pure, holy and impure, profane and pure, profane and impure (p. 10). There was trouble when impurity was introduced into the holy. For example, since the tent of meeting (and by extension the temple) was Yahweh’s holy residence on earth, the introduction of impurities into it risked the departure of his presence from it. “The consequence of polluting holy space is that, if left unaddressed, the impurity will cause God who dwells in the temple to forsake it,” Thiessen observes (pp. 15-16). It was to avoid such a disaster that the Levitical system was put in place with its rules and regulations about holiness and purity.

But what constituted “impurity”? Thiessen contends that there were two overlapping categories of impurity: ritual and moral. Ritual impurity was not in and of itself sinful but, if not taken care of, could lead to moral impurity. There were “three major sources of ritual impurity” per the Levitical system: genital discharges, lepra, and corpses (p. 15). Here Thiessen follows the work of Jacob Milgrom and it is from Milgrom that inspiration for the title of the book, Jesus and the Forces of Death, got its name. He notes that Milgrom viewed these three sources as representing death: “the corpse, obviously, is a dead body; the lepros – that is, the one suffering from lepra – looks corpse-like; and those who experience a genital discharge suffer the loss of life force contained in genital blood or semen” (p. 16). The priests who served in the temple, then, were vanguards for life, “divinely tasked with the central job of creating and maintaining boundaries to keep the forces of impurity contained so that they imperiled neither God’s presence nor Israel’s coexistence with God” (p. 18). Thiessen also notes that when the priests failed in their holy task, the prophets of Israel stepped in to decry their failure. But they do not call for the abandonment of the ritual purity system but rather they call Israel to “a more accurate delineation and maintenance of boundaries” (p. 19). They also looked forward to a day when impurities would be no more because God would deal with them more directly through a messianic agent. As we approach the dawning of the first-century CE, the expectation was that Yahweh would deal directly with the sources of impurity through a messianic agent. It is in this apocalyptic context[6] that the Gospel writers introduce Jesus as “the holy one of God” (Mark 1:24), “a man who embodies a contagious power or force that is opposed to and ultimately destroys the powers the create impurity and death” (p. 20).

In ch. 2 (pp. 21-41), Thiessen begins with the beginning of Jesus’ life and ministry. In the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, that beginning constitutes a discussion of Jesus’ family and upbringing, while in the Gospel of Mark it constitutes a baptism at the hands of John the Baptist (Mark 1:4-11). He writes that while modern readers, especially Christians, associate the baptism of John to the Christian rite of baptism, “Jews in Jesus’s day would have connected John to contemporary ritual bathing practices” (p. 22). And while little is known of John’s specific ritual, Jesus’ baptism by him nevertheless “situate[s] Jesus within the context of Jewish ritual purifications,” suggesting “that he was sympathetic to the priestly vocation of distinguishing pure from impure and keeping the holy realm distinct from the profane” (p. 23). While we do not know John’s pedigree from the Gospels of Mark or Matthew, in the Lukan Gospel his family is entirely Levitical, and his father serves as a priest in the temple of Jerusalem (Luke 1:5-7). John is seen on some level as “a priestly figure” (p. 23).

Thiessen turns his attention to Jesus’ pedigree as recorded in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, devoting most of the remaining chapter to the depiction of Jesus found in the Lukan. There exists in the Gospel of Luke an “emphasis upon Torah piety” concerning both John the Baptist’s family and Jesus’. In Luke 2, following Jesus’ birth, the family follows Torah to the “T,” circumcising Jesus on the eighth day (v. 21; cf. Genesis 17:10-12). In v. 22, the family goes up to Jerusalem “for their purification according to the law of Moses.” Their purification? As Thiessen points out, the reference to “their purification” is viewed as erroneous by some scholars. But Thiessen disagrees, and offers a lengthy yet compelling explanation as to why Luke speaks of “their [i.e., Mary’s and Jesus’] purification.” In short, the Levitical author implies that the newborn, by virtue of his coming into contact with his mother’s genitals and the blood of childbirth, has become impure. Such a view, Thiessen contends is implied in both Jubilees (3:8-13) and in 4Q265 from Qumran. In those two texts, the creation of Adam and Eve is connected to childbirth. In Jubilees, Adam is not permitted into the Garden for forty days and Eve for eighty (3:9) a claim directly connected to the Levitical stipulation that a woman who gives birth to a male is unclean for forty days (Leviticus 12:2-4) and a female for eighty days (Leviticus 12:5). Luke, Thiessen argues, is aware of such a view, and knows that “if he is not careful in his depiction of Jesus’s presentation at the temple, he might inadvertently depict the infant Jesus polluting God’s temple” (p. 37). Thus, Luke’s “their purification” is in keeping with the implied logic of Leviticus 12 as well as the views of later Jewish authors. “It is not Luke…who betrays his ignorance of actual Jewish customs and of the Jewish ritual purity system in the first century CE; it is modern scholars,” Thiessen forcefully argues (p. 38). Moreover, at the end of the chapter he notes that the Gospels “provide evidence of the legal diversity of early Jews” (p. 41) correctly portraying them not as a monolith but as a world of variety concerning a number of views about the Torah and what it requires.

Chapter three (pp. 43-68) features a discussion of “the walking dead,” i.e., those with the condition of lepra. Thiessen correctly observes that lepra is not the same as leprosy (i.e., Hansen’s disease) and its description as found in the book of Leviticus (Hebrew, ṣāraʿat), particularly its whiteness on the skin (cf. Leviticus 13) is nothing like the leprosy we know of today. Ancient medical texts also make a distinction between lepra and leprosy and descriptions of lepra-like skin diseases can be found throughout writings in the ancient Near East and in the Greco-Roman world. In the Second Temple period, a lepros was viewed as one who oozed ritual impurity such that “many Jews in the first century CE would have that that the lepros needed to exercise vigilance in maintain distance from people so as not to transmit his or her impurity to other Jews,” even if they disagreed exactly what that entailed (p. 54).

Following his explanation of lepra and how it functioned in the ancient world, Thiessen examines the story of Jesus found in Mark 1:40-45. The weight of lepra is felt in this text for, as Thiessen observes, if it was little more than a rash and not something able to transmit ritual impurity, why would the Gospel writers have felt the need to include in their accounts a story of Jesus healing it? “The answer must be that they did not want to demonstrate Jesus’ opposition to Jewish ritual concerns about lepra, as is so often the argument of New Testament scholars; rather, these early followers of Jesus wanted to depict him in a way that showed his opposition to the very existence of lepra itself” (pp. 54-55). In so doing, then, the Gospel writers depict a Jesus who is very much concerned with maintaining the ritual purity system found in Leviticus and in place during the first century. In fact, Jesus is careful to maintain boundaries for while he makes the lepros clean, he is unable to formally declare him clean and so sends him to the priest in keeping with Torah (Mark 1:44). Thiessen writes that “Jesus…fits within the larger stream of Jewish thinking about the declarative role that priests must play with regard to lepra” (p. 61). The Markan view is expanded upon further by the Matthean and Lukan authors who in their respective Gospels suggest that the healing of leproi is “precisely what the messiah would do, a central messianic work” (p. 65; cf. Matthew 11:5; Luke 7:22). Jesus is God’s agent to deal with ritual impurity, including lepra.

In ch. 4 (pp. 69-96), Thiessen takes a look at an intercalated story found in Mark 5:21-43. As Jesus is on his way to heal a child on the verge of death, he is suddenly pressed upon by a large crowd (vv. 21-24). In this crowd is a woman who is described as one “who had been suffering from hemorrhages for twelve years” (v. 25). She touches Jesus’ cloak and her hemorrhage stopped (v. 29). The reason this story is addressed in JFD is because the woman, due to her ailment, is considered a zavah, a woman with an abnormal genital discharge (Leviticus 15:25-30). As such, she is unclean. As Thiessen notes, in the era during which Jesus lived, a zavah would not have been permitted into sacred spaces, cut off from the divine. Moreover, the nature of her condition would have rendered her unable to have children. Her suffering runs deep.

Her solution in the story is to touch the one who she has heard can provide healing. She “did not seek the abolishment of the ritual purity system; rather, she sought the destruction of a disease that consigned her to a life of long-term impurity” (p. 89). While the woman has been suffering “an uncontrolled discharge of blood,” she touches a man who has an uncontrolled discharge of power (p. 91).[7] Jesus, as God’s holy one, cannot help but exude the power of his messianic, spirit-fueled ministry. And, as Thiessen concludes, this story in particular depicts a Jesus who “is innately, one could say ontologically, opposed to ritual impurity and that his body, like a force of nature, inevitably will destroy impurity’s sources” (p. 96).

“Every time Jesus encounters a corpse, it returns to life,” Thiessen writes at the beginning of ch. 5 (pp. 97-122). But what are the implications of this as it pertains to the ritual purity system? For example, in Mark 5, Jesus touches the hand of a corpse and raises it to life (vv. 41-42). Yet, “corpses were the most powerful source of impurity in the ritual purity system” (p. 99; cf. Numbers 19:17-19). In the Second Temple period, the ohel of Numbers 19 which was the tent of meeting becomes an oikos in the LXX and a bayit in the DSS. Consequently, a common view was that corpse impurity was even more serious, extending to all buildings. For Jesus to touch a corpse meant he became impure.

As Thiessen notes, “there is nothing unlawful or sinful about Jesus contracting corpse impurity from the dead girl” of Mark 5 (p. 109). He’s not a priest and he has taken no vow like that of the Nazarites. Nor is it the case that Jesus is disregarding the purity laws. By merely entering the house, anyone who did so would have become impure. But what is interesting about this story is that Jesus enters the house to do something that no priest could do: raise the girl to life. That is, in raising her to life the “girl’s body has been separated from the source of her impurity – death” (p. 109). Jesus’ efficacious, death-reversing power is evident in the other Gospels, including the Gospel of John where Jesus can raise the dead from a distance with merely his voice (John 11:43). Thiessen writes, “Jesus’s power is infectious even at a distance, just like a corpse’s pollution infects at a distance” (p. 122).

In ch. 6 (pp. 123-148), the book turns to the demonic. Readers of the Synoptics know that Jesus is often depicted as an exorcist. But what many readers don’t know is that demons were often associated with that which would have been considered ritually impure. Though largely absent from the Hebrew Bible and viewed in different ways in the ANE and Greco-Roman worlds, in the Second Temple period demons are often associated with pollution of the earth. For example, in Jubilees, demons affect the sons of Noah after the flood. Many of these demons are considered “unclean spirits,” and in some Jewish literature are actually the spirits of the dead. Thus, in all of Second Temple literature save for Philo, “demonic beings are always evil. What motivates these beings is a desire to deceive, injure, and destroy humans” (p. 138).

It is no surprise then that such entities Jesus must face in his ministry as God’s holy one. In fact, in the scene where Jesus is called “the holy one of God,” the title comes from the lips of a man who has an “unclean spirit” (Mark 1:23-24). “This initial story,” Thiessen observes, “sets the tone for the rest of Mark’s portrayal of Jesus” (p. 142). Because Jesus is imbued with God’s holy spirit, it is blasphemous to accuse him of doing anything but God’s will in eliminating the demonic threat. Further, “Jesus’s exorcism of demons is the preeminent sign of the coming of God’s kingdom and of the end of Satan’s rule over humanity” (p. 147).

Chapter seven (pp. 149-176) turns to the subject of the sabbath, something I brought up in the introduction to this review. According to the Hebrew scriptures, the sabbath has its roots in creation. The Priestly author of Genesis 1 frames the creation of the world as a week of activity, the end of which is capped by the Israelite god resting (Hebrew, šābat) and then sanctifying (Hebrew, qādaš) it (Genesis 2:2-3). Thus, we find in the Torah commands to rest on the sabbath and, because of its inherent holiness, the penalty of death for those who violate it. But as Thiessen points out, later interpreters didn’t always take this hard-liner view of the sabbath: “it was precisely here that Jews could disagree with one another” (p. 154). There was debate over what actually constituted “work,” some arguing, for example, that picking fruit of the ground was a violation of the sabbath while others thought that it wasn’t.

In Mark 2, Jesus’ disciples are accused of violating the sabbath because they plucked heads of grain on it (vv. 23-24). But the Markan Jesus contends that “[t]he sabbath was made for humankind, and not humankind for the sabbath” (v. 27). The way Jesus goes about reaching that conclusion is not entirely obvious, but Thiessen helpfully fills in the gaps, noting that Jesus seems to be reasoning with some implicit assumptions. In short, the Markan Jesus assumes that hunger and need are greater than Torah legislation concerning the tent of meeting (and temple) and that the temple is of greater importance than the sabbath. Thus, hunger and need are greater than the sabbath (pp. 158-159). This doesn’t mean Jesus does away with either the need for the sabbath or the temple. Instead, he works within the Jewish logic that assumes their necessity but argues that hunger and need are more important. And Thiessen shows that this kind of view coheres with those of other Jewish thinkers. “According to both the Jesus of the Gospels and many rabbis, human life takes precedence over the Sabbath” (p. 173).

In the conclusion of Thiessen’s volume (pp. 177-185), he wraps up all that he has argued in the previous chapters. He emphasizes the centrality of the ritual purity system in the minds of the Gospel writers as well as their belief that “God had introduced something new into the world to deal with the sources of these impurities: Jesus” (p. 179). This is important because what Thiessen has argued throughout is not that the Gospel writers thought Jesus was doing away with the ritual impurity system but instead he was demolishing ritual impurity itself. Moreover, the Evangelists thought that Jesus not only destroyed impurity but gave his disciples the power to do so as well. This is seen quite clearly in the Acts of the Apostles where “the apostles continue to address both [death] and the devil throughout the narrative” (p. 184), an indication that the work of dealing with impurity has yet to be completed. Jesus’ ministry was but the first yet crucial step in the process by which God himself would overcome all that was wrong with the world.

At the end of JFD, Thiessen has placed a helpful appendix (pp. 187-195) that addresses a related claim concerning kosher food. In many readings of Mark 7:19, Jesus effectively does away with the regulations of the Torah concerning food. Thiessen shows that this isn’t what is going on in Mark 7 since the debate over handwashing assumes the logic of what is kosher and what is not. In other words, “the story simply does not intend to deal with the question of whether one should eat pork or shellfish; rather, it intends to address the question of whether one can defile kosher food with one’s ritually impure hands and then introduce that impurity into one’s body by the consumption of that defiled food” (p. 192). The Pharisees thought you would while Jesus thought you wouldn’t. Moreover, Thiessen notes that Jesus’ view that moral impurity was far more important than ritual impurity (e.g., Mark 7:20-23) coheres with the views of other Jews of his era (p. 192). They were no less Jewish than he.

CONCLUSION

I grew up in a tradition that often emphasized the Jewishness of Jesus but otherwise cherry-picked what he had to say to fit an antinomian agenda.[8] When I began attending college at Pensacola Christian College, I ran into almost the opposite. We weren’t even allowed to go to the sports fields to play a game of basketball. In both cases, the words of Jesus were employed to promote a particular view about the sabbath. And in both cases, neither side truly appreciated how Jesus’ words and actions fit into their first century Jewish context.

This is why Thiessen’s book is important. In providing historical context for how the Evangelists portray Jesus, readers are better able to see Jesus’ words for what they are: the musings of a Jewish man of the early first century CE about topics important to Jewish people. Moreover, Thiessen also shows us that the Gospel writers depict Jesus in an apocalyptic context, specifically in dealing with the “forces of death” ritual impurities represent. For these writers, God was at work in the world through Jesus to do away with these forces and bring about a kingdom in which such impurities find no home.

Understanding the Jesus of the Gospels can be hard work. Thiessen shows that it is also rewarding work.

[1] Joel Marcus, Mark 1-8: A New Translation with Commentary, The Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), 247; R.T. France, The Gospel of Mark, NIGTC (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2002), 149.

[2] D.A. Carson, “Jesus and the Sabbath in the Four Gospels,” in From Sabbath to Lord’s Day: A Biblical, Historical, and Theological Investigation, D.A. Carson, editor (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 1982), 85. Carson writes with regard to Jesus and the Law in Matthew and Mark (p. 80),

Jesus’ view of the law appears to be ambivalent. He emphasizes that it is from God and that Scripture cannot be broken; yet in another sense, “law” continues only to John, and then the kingdom to which it points takes over. Although this is emphasized in Matthew, it is not peculiar to his gospel, for Jesus is the eschatological center of Mark as well, even though Mark does not treat fulfillment themes extensively. And in Luke, the fulfillment motifs again come to the fore, albeit with slightly different emphases (cf. Luke 24:27-44).

[3] Thomas R. Schreiner, New Testament Theology: Magnifying God in Christ (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008), 620.

[4] Schreiner, New Testament Theology, 621, 622.

[5] Matthew Thiessen, Jesus and the Forces of Death: The Gospels’ Portrayal of Ritual Impurity within First-Century Judaism (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2020).

[6] Martinus C. de Boer (Paul: Theologian of God’s Apocalypse – Essays on Paul and Apocalyptic [Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2020], 208-209) notes that in the apocalyptic mindset the current age “is characterized by death” and human beings are unable to do anything to alter this. Therefore, it is up to God to deal with death and, I would add (following Milgrom and Thiessen) the forces that cause it.

[7] Here Thiessen draws upon the work of Candida Moss in her insightful piece, “The Man with the Flow of Power: Porous Bodies in Mark 5:25–34,” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 129, no. 3 (Fall 2010), 507-519.

[8] For example, see Peter S. Ruckman, Why I Am Not a Seventh Day Adventist (Pensacola, FL: Bible Baptist Bookstore, 1997).

4 thoughts on “Book Review: ‘Jesus and the Forces of Death’ by Matthew Thiessen”